Historically found in Cambodia, China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam, this species decline is large. In 2010, the assessment was that there were 250 left in Thailand, with around 85 in Myanmar and perhaps 20 hanging on in Vietnam. It is thought that the population is now just 250. This sub-species is found in Myanmar(85)) and Thiland(237), with a total population of an estimated 342 individuals. Back in 2009-2014 the population was thought to be between 189-252 in this period. Vietnam is only thought to have 5 remaining, while Laos is thought to have 2. Historically, it was also found in Cambodia and China. Historically, it is thought that this species range would have gone further North, potentially up to Chittagong Hill Tracts and Brahmaputra River basin, where the Bengal tiger populations range ended.

In Myanmar, surveys were conducted between 1999 and 2002, confirming the presence of tigers in the Hukawng Valley, Htamanthi Wildlife Sanctuary and in two small areas in the Tanintharyi Region. The Tenasserim Hills is an important area, but forests are harvested there (which means that they may be too much disruption for the tiger to survive here). In 2015, a camera trap took an image of a tiger in the hill forests of Kayin State. Camera trap surveys between 2016 and 2018 revealed about 22 adult individuals in three sites that represent 8% of the potential tiger habitat in the country. How many the rest of the country could support even if they had to be reintroduced is beyond the scope of this.

More than half of the total Indochinese tiger population survives in the Western Forest Complex in Thailand (Covering an area of about 18,000 sq. km. extended into Myanmar border along the Tennaserim Range and abreviated to (WEFCOM)) is considered as the largest remaining forest track in the mainland Southeast Asia that is made up of 17 protected areas (without gaps between them; 11 national parks and 6 wildlife sanctuaries.), especially in the area of the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. This habitat consists of tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests. Camera trap surveys from 2008 to 2017 in eastern Thailand detected about 17 adult tigers in an area of 4,445 km2 (1,716 sq mi) in Dong Phayayen–Khao Yai Forest Complex. Several individuals had cubs. The population density in Thap Lan National Park, Pang Sida National Park and Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary was estimated at 0.32–1.21 individuals per 100 km2 (39 sq mi). Three subadult tigers were photographed in spring 2020 in a remote region of Thailand that are thought to be dispersing – moving out of areas which they were born into, and trying to find territory of their own.

In Laos, 14 tigers were documented in Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area during surveys from 2013 to 2017, covering four blocks of about 200 km2 (77 sq mi) semi-evergreen and evergreen forest that are interspersed with some patches of grassland. Surveys that have been carried out since, have failed to detect any tigers, and the likelihood is that they have been extirpated as a result of poaching. Given the huge value of dead tigers in Chinese medicine, this is not a big surprise, as the current value for a carcass of a dead tiger is around £67,000 before doing anything with it, the value of it after extracting everything used in Chinese medicine (no evidence that it does anything) is around 5 times higher or £335,000. That is a huge windfall, but given that the average salary in Thailand is about £2200 a year (meaning that while many earn a great deal more than this, also many earn much less). 335,000, therefore represents perhaps 150 years of average salary. This is another place, where tourism can help. A thriving tourism industry will bring well paid jobs to many, and will therefore, not only preserve the tiger, but has the capacity of lifting many communities out of destitution.

In eastern Cambodia, tigers were last recorded in Mondulkiri Protected Forest and Virachey National Park during surveys between 1999 and 2007. In 2016, the Cambodian government declared that the tiger was “functionally extinct”. In April 2023, India signed a memorandum of understanding with Cambodia to assist the country with the tiger’s reintroduction. At least 90 acres (36 ha) of the Cardamom Mountains of Tatai Wildlife Sanctuary could be used to host Bengal tigers (though this if a correct number is not going to do much for a wild tiger).

From the 1960s and earlier, the Indochinese tiger occurred throughout the mountains in Vietnam, even in the midlands and Islands. In the report of the Government of Vietnam at the Tiger Forum in 2004, there would be tigers in only 17 provinces and they were living in fragmented and severely degraded forest areas. Tigers were still present in 14 protected areas in the 1990s, but none have been recorded in the country since 1997. There is news of its extinction in both countries. In Laos, no tiger has been seen since 2013, when its populations were estimated at only two, and these two individuals simply vanished shortly after 2013 from Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area, denoting they were most likely killed either by snare or gun. In Vietnam, a 2014 IUCN Red List report indicated that tigers were possibly extinct in Vietnam.

In China, it occurred historically in Yunnan province and Mêdog County, where it probably does not survive today. Thus, probably the Indochinese tiger now only survives in Thailand and Myanmar. In Yunnan’s Shangyong Nature Reserve, three individuals were detected during surveys carried out from 2004 to 2009.

In Thailand’s Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, 11 individual tigers were equipped with GPS radio collars between June 2005 and August 2011. Females had a mean home range of 70.2km2 (27.1 sq mi) and males of 267.6km2 (103.3sq mi).

Between 2013 and 2015, 11 prey species were identified at 150 kill sites. They ranged in weight from 3 to 287 kg. Sambar deer, banteng, gaur, and wild boar were most frequently killed, but also remains of Asian elephant calves, hog badger, Old World porcupine, muntjac, serow, pangolin, and langur species were identified.

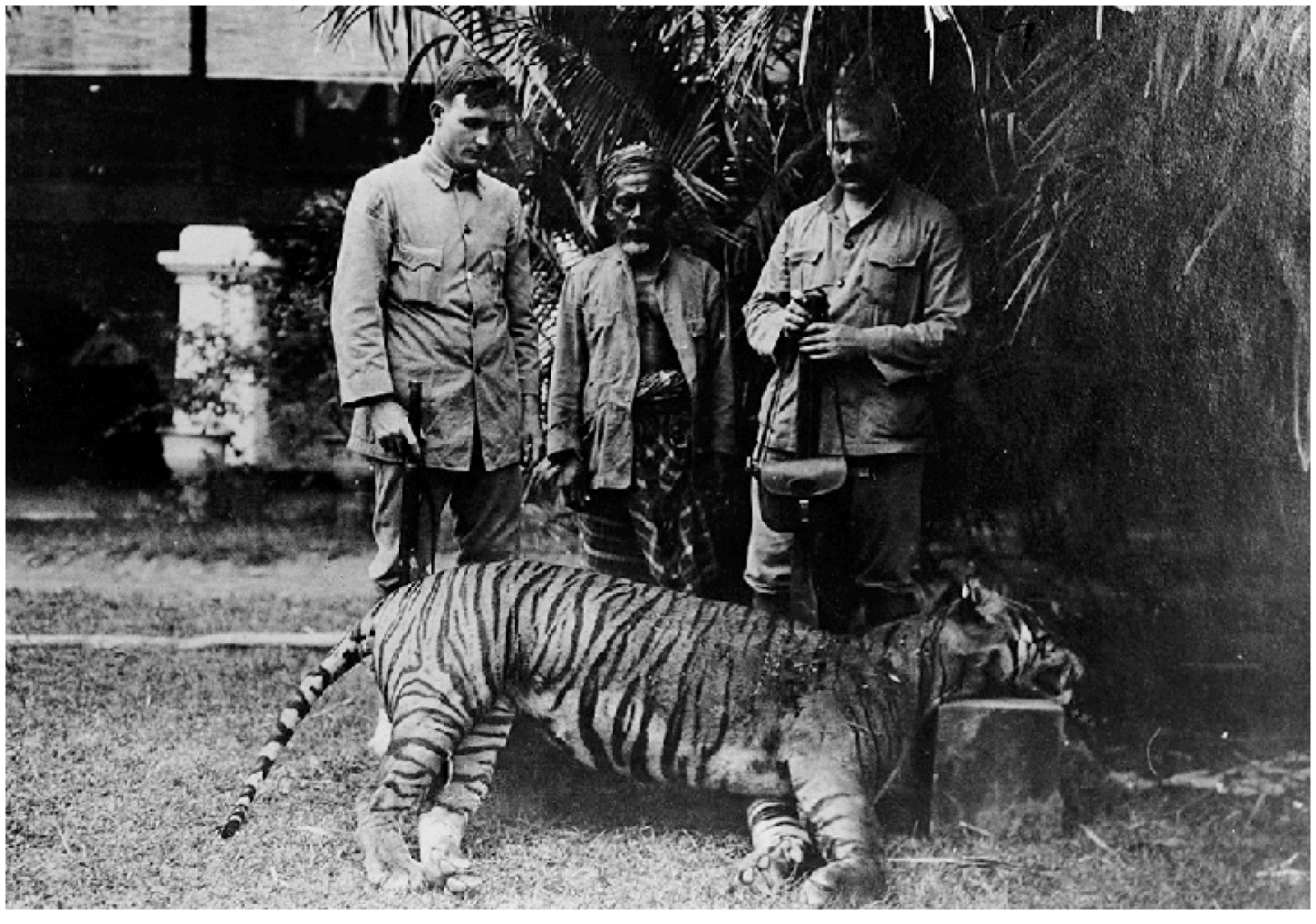

The primary threat to the tiger is poaching for the illegal wildlife trade. Tiger bone has been an ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine for more than 1,500 years and is either added to medicinal wine, used in the form of powder, or boiled to a glue-like consistency. More than 40 different formulae containing tiger bone were produced by at least 226 Chinese companies in 1993. Tiger bone glue is a popular medicine among urban Vietnamese consumers.

Between 1970 and 1993, South Korea imported 607 kg of tiger bones from Thailand and 2,415 kg from China between 1991 and 1993. Between 2001 and 2010, wildlife markets were surveyed in Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos. During 13 surveys, 157 body parts of tigers were found, representing at least 91 individuals. Whole skins were the most commonly traded parts. Bones, paws, and penises were offered as aphrodisiacs in places with a large sex industry. Tiger bone wine was offered foremost in shops catering to Chinese customers. Traditional medicine accounted for a large portion of products sold and exported to China, Laos, and Vietnam. Between 2000 and 2011, 641 tigers, both live and dead, were seized in 196 incidents in Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, and China; 275 tigers were suspected to have leaked into trade from captive facilities. China was the most common destination of the seized tigers.

In Myanmar’s Hukaung Valley, the Yuzana Corporation, alongside local authorities, has expropriated more than 200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of land from more than 600 households since 2006. Much of the trees have been logged, and the land has been transformed into plantations. Some of the land taken by the Yazana Corporation had been deemed tiger transit corridors. Without this land, smaller reserves can instantly become incapable of supporting tigers longterm. These are areas of land that were supposed to be left untouched by development in order to allow the region’s Indochinese tigers to travel between protected pockets of reservation land.

Since 1993, the Indochinese tiger has been listed on CITES Appendix I, making international trade illegal. China, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, and Taiwan banned trade in tigers and sale of medicinal derivatives. Manufacture of tiger-based medicine was banned in China, and the open sale of tiger-based medicine reduced significantly since 1995.

Patrolling in Thailand’s Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary has been intensified since 2006 so that poaching appears to have been reduced, resulting in a marginal improvement of tiger survival and recruitment. By autumn 2016, at least two individuals had dispersed to adjacent Mae Wong National Park; six cubs were observed in Mae Wong and the contiguous Khlong Lan National Park in 2016, indicating that the population was breeding and recovering.[43]

In Thailand and Laos, this tiger is considered Endangered, while it is considered Critically Endangered in Vietnam and Myanmar. Of course, if all this is correct, then some of these countries should amend their listing to extinct.

The Indochinese tiger is the least represented in captivity and is not part of a coordinated breeding program. As of 2007, 14 individuals were recognized as Indochinese tigers based on genetic analysis of 105 captive tigers in 14 countries. This is no where near enough to be able to do a reintroduction.

I will hope to add links to help arrange travel to see this species, do get in touch if you can help

More than half of the total Indochinese tiger population survives in the Western Forest Complex in Thailand, especially in the area of the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary.

They are considered endangered in Thailand and critically endangered in Myanmar and Vietnam

The

The

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species.

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species. common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

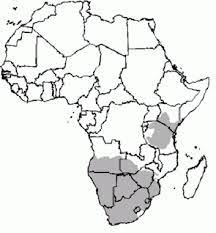

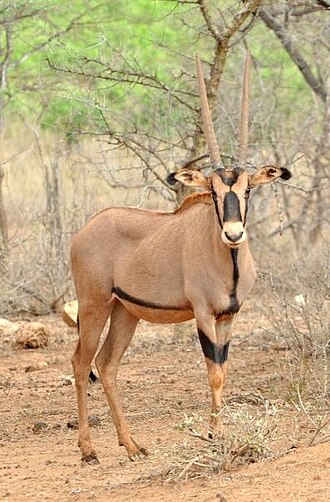

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

Impala

Impala antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

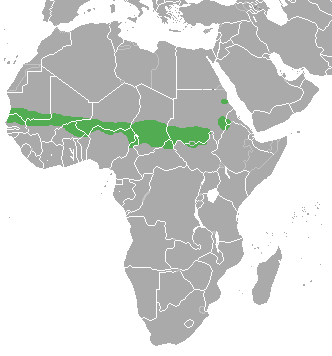

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle.

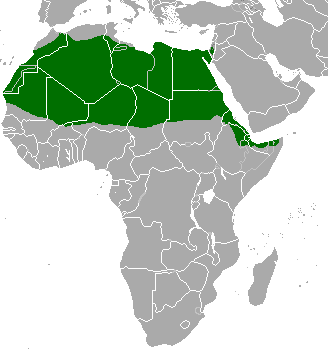

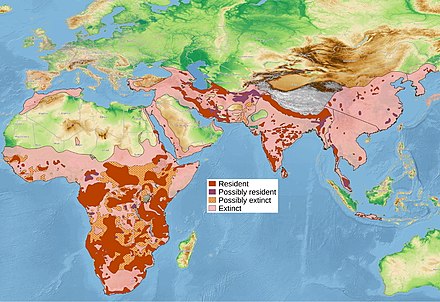

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle. Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places. A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice. The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams.

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams.  The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink. A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda. The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

The Arabian Tahr is a species of Tahr found in eastern Arabia. They were recently moved to their own genus Arabitragus. It is the smallest Tahr species, and both genders have rear facing small horns. They have longish fur of redish brown fur, with a black stripe running down its back. They live in the Hajar Mountains in Oman and the United Arab Emirates, at evelation of up to 1800m.

The Arabian Tahr is a species of Tahr found in eastern Arabia. They were recently moved to their own genus Arabitragus. It is the smallest Tahr species, and both genders have rear facing small horns. They have longish fur of redish brown fur, with a black stripe running down its back. They live in the Hajar Mountains in Oman and the United Arab Emirates, at evelation of up to 1800m. The Barbary Sheep, is found in a variety of locations across northern Europe. Biggest populations include

The Barbary Sheep, is found in a variety of locations across northern Europe. Biggest populations include

The Bharal is found in the high Himalayas.It is split into 3 subspecies

The Bharal is found in the high Himalayas.It is split into 3 subspecies

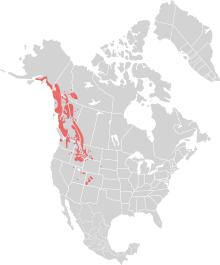

The mountain goat is sometimes referred to as the rocky mountain goat, as this is where it is found. They are incredibly sure-footed, and can often be seen seemingly defying gravity, standing on the steepest of cliffs. This appears to be a defence strategy, as lower down the mountains, brown bears and black bears, as well as

The mountain goat is sometimes referred to as the rocky mountain goat, as this is where it is found. They are incredibly sure-footed, and can often be seen seemingly defying gravity, standing on the steepest of cliffs. This appears to be a defence strategy, as lower down the mountains, brown bears and black bears, as well as  Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern

Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern

From the genus Ovibos, this map shows their range (blue is reintroductions, while red is historic range. In the long past, there were a variety of species that looked very much like this, however, not any more. The also evolved in Asia, before spreading to Europe and over to America. This map is hard to read, but they are found in Arctic areas of Alaska,

From the genus Ovibos, this map shows their range (blue is reintroductions, while red is historic range. In the long past, there were a variety of species that looked very much like this, however, not any more. The also evolved in Asia, before spreading to Europe and over to America. This map is hard to read, but they are found in Arctic areas of Alaska,  Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern India, western Bhutan and Nepal. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List, as the population is declining due to both hunting and habitat loss – with the population in its native range thought to be around 2200.

Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern India, western Bhutan and Nepal. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List, as the population is declining due to both hunting and habitat loss – with the population in its native range thought to be around 2200.

The Tibetan antelope also known as Chiru, is found in the area shown in the map to the left and is a medium-sized bovid native to the north-eastern Tibetan plateau. Most of the population live within the Chinese border, while some scatter across India and Bhutan in the high altitude plains, hill plateau and montane valley.

The Tibetan antelope also known as Chiru, is found in the area shown in the map to the left and is a medium-sized bovid native to the north-eastern Tibetan plateau. Most of the population live within the Chinese border, while some scatter across India and Bhutan in the high altitude plains, hill plateau and montane valley.

The Alpine Ibex is found throughout much of the Alps (as you can see in the map). It is also known as the Capra ibex, and the Steinbock.

The Alpine Ibex is found throughout much of the Alps (as you can see in the map). It is also known as the Capra ibex, and the Steinbock. The Bezoar ibex range is shown in the map to the left of this text. Unfortunately, they are not doing well, with only a few thousand left in the wild, primarily arouund the Caucasus.

The Bezoar ibex range is shown in the map to the left of this text. Unfortunately, they are not doing well, with only a few thousand left in the wild, primarily arouund the Caucasus.

The iberian Ibex is found throughout much eastern Iberian peninsular, with sporadic range in other parts of the peninsular. It is listed as least concern. There have been 4 subspecies identified but 2 are extinct. The surviving species are the western Iberian ibex and the Southeastern Iberian ibex (also known as the Beceite Ibex). They have an estimated combined population of 50,000 left in the wild. They are classed as least concern.

The iberian Ibex is found throughout much eastern Iberian peninsular, with sporadic range in other parts of the peninsular. It is listed as least concern. There have been 4 subspecies identified but 2 are extinct. The surviving species are the western Iberian ibex and the Southeastern Iberian ibex (also known as the Beceite Ibex). They have an estimated combined population of 50,000 left in the wild. They are classed as least concern. The Markhor is found through the green areas on the map (The markhor is a large wild Capra (goat) species native to South Asia and Central Asia, mainly within Pakistan, the Karakoram range, parts of Afghanistan, and the Himalayas. It is listed on the IUCN Red List as Near Threatened since 2015.)

The Markhor is found through the green areas on the map (The markhor is a large wild Capra (goat) species native to South Asia and Central Asia, mainly within Pakistan, the Karakoram range, parts of Afghanistan, and the Himalayas. It is listed on the IUCN Red List as Near Threatened since 2015.)

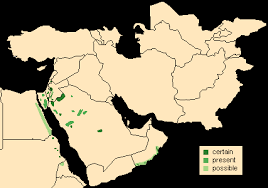

The Nubian Ibex has a relatively restricted range (as can be seen from the map to the left). The population across this area is under 5000, with the largest population in Israel (1200-1400). It is considered vulnerable. Their population has remained surprisingly stable over the last 10,000 years as the advent of domestic animals came in. Nubian Ibex, like other Ibex species take refuge on impossibly steep cliffs, and are more and more viligant the farther they are from these safe zones. This nimbleness also allows them to climb trees.

The Nubian Ibex has a relatively restricted range (as can be seen from the map to the left). The population across this area is under 5000, with the largest population in Israel (1200-1400). It is considered vulnerable. Their population has remained surprisingly stable over the last 10,000 years as the advent of domestic animals came in. Nubian Ibex, like other Ibex species take refuge on impossibly steep cliffs, and are more and more viligant the farther they are from these safe zones. This nimbleness also allows them to climb trees. The Siberian ibex is also known using regionalized names including Altai ibex, Asian ibex, Central Asian ibex, Gobi ibex, Himalayan ibex, Mongolian ibex or Tian Shan ibex.

The Siberian ibex is also known using regionalized names including Altai ibex, Asian ibex, Central Asian ibex, Gobi ibex, Himalayan ibex, Mongolian ibex or Tian Shan ibex.

The Walia Ibex does not have a large range (see it to the left). It is classed as vulnerable and numbers 450-500 in the wild, living in the Simien mountains of Ethiopia.

The Walia Ibex does not have a large range (see it to the left). It is classed as vulnerable and numbers 450-500 in the wild, living in the Simien mountains of Ethiopia. The west Asian Ibex (often referred to as wild goat) has the range shown on the left. It inhabits forests, shrubland and rocky areas across this range. It is classed as near threatened, largely as a result of degradation and destruction of their habitat. It is thought to be the ancestor of the domestic goat.

The west Asian Ibex (often referred to as wild goat) has the range shown on the left. It inhabits forests, shrubland and rocky areas across this range. It is classed as near threatened, largely as a result of degradation and destruction of their habitat. It is thought to be the ancestor of the domestic goat.

Native to this region of north America, there are 3 recognized subspecies, though in the past 7 were recognized.

Native to this region of north America, there are 3 recognized subspecies, though in the past 7 were recognized.

Also known as thin horn sheep, there are only 2 subspecies, being the nominate subspecies and the stone sheep.

Also known as thin horn sheep, there are only 2 subspecies, being the nominate subspecies and the stone sheep.

Also known as the Siberian bighorn sheep. They are

Also known as the Siberian bighorn sheep. They are

Also known as arkars, shapo, or shapu, is a wild sheep native to Central and South Asia. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and its range map is to the left.

Also known as arkars, shapo, or shapu, is a wild sheep native to Central and South Asia. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and its range map is to the left. The chamois or Alpine chamois is a species of goat-antelope native to the mountains in Southern Europe, from the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Apennines, the Dinarides, the Tatra to the Carpathian Mountains, the Balkan Mountains, the

The chamois or Alpine chamois is a species of goat-antelope native to the mountains in Southern Europe, from the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Apennines, the Dinarides, the Tatra to the Carpathian Mountains, the Balkan Mountains, the

The Pyrenean chamois is a goat-antelope that lives in the Pyrenees and Cantabrian Mountains of Spain,

The Pyrenean chamois is a goat-antelope that lives in the Pyrenees and Cantabrian Mountains of Spain,  Also known as a Thar, It is the official state animal of the Indian state of Mizoram. It has at various times been considered a separate species in its own right. At the moment, it is thought to be a subspecies of the mainland Serow, however it has moved back and forwards in recent years, so we will list them all.

Also known as a Thar, It is the official state animal of the Indian state of Mizoram. It has at various times been considered a separate species in its own right. At the moment, it is thought to be a subspecies of the mainland Serow, however it has moved back and forwards in recent years, so we will list them all.

It is found in dense woodland in

It is found in dense woodland in  As can be seen, the Mainland Serow includes the whole range of Himalayan Serow, and both species look very similar. It has already declined by 30% in the last 3 generations, and is classed as vulnerable. This is at least, in part, a result of deforestation and expansion of the palm oil industry. Unfortunately, there is no estimate at the current time, for the size of this wild population.

As can be seen, the Mainland Serow includes the whole range of Himalayan Serow, and both species look very similar. It has already declined by 30% in the last 3 generations, and is classed as vulnerable. This is at least, in part, a result of deforestation and expansion of the palm oil industry. Unfortunately, there is no estimate at the current time, for the size of this wild population.

Also known as the Burmese red serow, the range of this species (or possibly subspecies, as it has at time been thought of as a subspecies of the Sumatran Serow) is shown in the map to the left.

Also known as the Burmese red serow, the range of this species (or possibly subspecies, as it has at time been thought of as a subspecies of the Sumatran Serow) is shown in the map to the left. This map shows the range of all serow species (or subspecies) the Southern Serow, inhabits the grey range that is lowest on the map. They are classed as vulnerable to extinction. There is no estimate for them across their whole range, but the population of Malaysia is thought to be between 500-750.

This map shows the range of all serow species (or subspecies) the Southern Serow, inhabits the grey range that is lowest on the map. They are classed as vulnerable to extinction. There is no estimate for them across their whole range, but the population of Malaysia is thought to be between 500-750.

The Taiwanese Serow (also known as the Formosan Serow) lives on the island of Taiwan. It is classed as least concern, but there is no concrete estimate on its wild numbers. Generally browsers, they are very shy, and are usually not seen, merely known of there prescense from their droppings.

The Taiwanese Serow (also known as the Formosan Serow) lives on the island of Taiwan. It is classed as least concern, but there is no concrete estimate on its wild numbers. Generally browsers, they are very shy, and are usually not seen, merely known of there prescense from their droppings. Also known as the grey long-tailed goral or central Chinese goral, is a species of goral, a small goat-like ungulate, native to mountainous regions of Myanmar, China, India,

Also known as the grey long-tailed goral or central Chinese goral, is a species of goral, a small goat-like ungulate, native to mountainous regions of Myanmar, China, India,

The Himalayan goral also known as the gray goral, is a bovid species native to the Himalayas. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List because the population is thought to be declining significantly due to habitat loss and hunting for meat. It is also on CITES appendix 1 which bans trade. There is no estimate on numbers.

The Himalayan goral also known as the gray goral, is a bovid species native to the Himalayas. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List because the population is thought to be declining significantly due to habitat loss and hunting for meat. It is also on CITES appendix 1 which bans trade. There is no estimate on numbers. This species is not living in the best place for active conservation, and it is thought taht there may be only 250 left in the wild. Much of this species population live along the borders of North Korea. In some ways this is positive, as the way the country has been run, means that animals lost elsewhere still thrive here (there is possibly still tigers in north korea). Apart from during the rut when males roam far and wide, each individual tends to stay within a 100 acre area.

This species is not living in the best place for active conservation, and it is thought taht there may be only 250 left in the wild. Much of this species population live along the borders of North Korea. In some ways this is positive, as the way the country has been run, means that animals lost elsewhere still thrive here (there is possibly still tigers in north korea). Apart from during the rut when males roam far and wide, each individual tends to stay within a 100 acre area.

The red goral is considered vulnerable to extinction (a better situation than many other goral species (or perhaps subspecies). The upper bound for its population is thought to be around 10,000, though it is thought by many, that the population is likely to be very much lower.

The red goral is considered vulnerable to extinction (a better situation than many other goral species (or perhaps subspecies). The upper bound for its population is thought to be around 10,000, though it is thought by many, that the population is likely to be very much lower.

50 years ago, Africa was estimated to have 700,000 the current number is nearer to 50,000 (the 700,000 figure came from a study in 1988, estimates vary widely, when I have written all my African leopard pages, I will give an estimate based on all the country estimates (it should be noted, however that this may be no more accurate). This is not evenly spread, such that while 34 countries are thought to still host them. It should be noted, that the so called Barbary leopard is included in this subspecies. While there is still much debate (not least the suggestion that the Sahara might have stopped gene from from the Barbary region to the rest of Africa. In a similar way, there is discussion on a variety of different populations of leopards, but these will not get their own tab, until they are declared as recognized subspecies (there was, at one time as many as 37 claimed different subspecies of leopard spread across Africa and Asia, many were lost, when the genetic differences were found to be so small).

50 years ago, Africa was estimated to have 700,000 the current number is nearer to 50,000 (the 700,000 figure came from a study in 1988, estimates vary widely, when I have written all my African leopard pages, I will give an estimate based on all the country estimates (it should be noted, however that this may be no more accurate). This is not evenly spread, such that while 34 countries are thought to still host them. It should be noted, that the so called Barbary leopard is included in this subspecies. While there is still much debate (not least the suggestion that the Sahara might have stopped gene from from the Barbary region to the rest of Africa. In a similar way, there is discussion on a variety of different populations of leopards, but these will not get their own tab, until they are declared as recognized subspecies (there was, at one time as many as 37 claimed different subspecies of leopard spread across Africa and Asia, many were lost, when the genetic differences were found to be so small).

The number of Indian leopards in the wild is a worryingly low number. Some places suggest around 9500, while others suggest 12,000-14,000 (remember that the area of

The number of Indian leopards in the wild is a worryingly low number. Some places suggest around 9500, while others suggest 12,000-14,000 (remember that the area of

In 2008, the size of this subspecies left in the wild was thought to be between 45 and 200. As such, it is perhaps not surprising that this subspecies has been critically endangered since 1996.

In 2008, the size of this subspecies left in the wild was thought to be between 45 and 200. As such, it is perhaps not surprising that this subspecies has been critically endangered since 1996.

Caucasian (also called Persian) Leopard)

Caucasian (also called Persian) Leopard)

Only described in 1956, they are relatively similar to the Indian Leopard, and were thought to be part of that subspecies until then. There are only 800 of this subspecies of leopard, and they were listed as vulnerable in 2020, and unfortunately it is thought to still be declining. It is thought, that as a result of being the apex predator on the island, they have got bigger.

Only described in 1956, they are relatively similar to the Indian Leopard, and were thought to be part of that subspecies until then. There are only 800 of this subspecies of leopard, and they were listed as vulnerable in 2020, and unfortunately it is thought to still be declining. It is thought, that as a result of being the apex predator on the island, they have got bigger.

Records from before 1930 suggest that this species of Leopard used to live near Beijing and in the mountains to the North-west. The wild population is estimated at around 110, so is one of the more endangered leopard species in the world. It is thought that this population and the Amur Leopard species were connected until just a few hundred years ago. As such, it may well be possible to boost genetic variability if that were to become necessary.

Records from before 1930 suggest that this species of Leopard used to live near Beijing and in the mountains to the North-west. The wild population is estimated at around 110, so is one of the more endangered leopard species in the world. It is thought that this population and the Amur Leopard species were connected until just a few hundred years ago. As such, it may well be possible to boost genetic variability if that were to become necessary.

Like many cats – both big and lesser cats, they have rare colourings. These are not separate species, instead they are either melanistic, or albino.

Like many cats – both big and lesser cats, they have rare colourings. These are not separate species, instead they are either melanistic, or albino.

The country with the most tigers is India, hosting around 70% of the remaining tigers, or a little over 3000. However, this is down from 100,000 in 1900. In 2006 the Indian tiger population was as low as just 1411 – there are individual reserves in Africa with more lions in than this number. Given that there are 54 tiger reserves in India, that leaves an average population of just 30 per reserve – translocation will be required to maintain genetically healthy tigers. Formerly working on pug-marks, counting has been replaced with photo identification, as pug marks were overestimating the population (Simlipal reserve in Orissa state claimed 101 tigers in 2004, yet in 2010 a photo count stated 61, and this is thought a a huge over estimate, as the same state government claims just 45 tigers across the state. Sariska and Panna reserves in India are worse with the government having to admit that there are no tigers left (2 reserves of at least 5 so called tiger reserves with none left).

The country with the most tigers is India, hosting around 70% of the remaining tigers, or a little over 3000. However, this is down from 100,000 in 1900. In 2006 the Indian tiger population was as low as just 1411 – there are individual reserves in Africa with more lions in than this number. Given that there are 54 tiger reserves in India, that leaves an average population of just 30 per reserve – translocation will be required to maintain genetically healthy tigers. Formerly working on pug-marks, counting has been replaced with photo identification, as pug marks were overestimating the population (Simlipal reserve in Orissa state claimed 101 tigers in 2004, yet in 2010 a photo count stated 61, and this is thought a a huge over estimate, as the same state government claims just 45 tigers across the state. Sariska and Panna reserves in India are worse with the government having to admit that there are no tigers left (2 reserves of at least 5 so called tiger reserves with none left).

Russia hosts one of the hardest tigers to see. However, there are now around 500 Amur tigers roaming the remote far east of Russia, up from less than 40 in the 1940s, this population has also had great gains.

Russia hosts one of the hardest tigers to see. However, there are now around 500 Amur tigers roaming the remote far east of Russia, up from less than 40 in the 1940s, this population has also had great gains.