Flamingoes and Grebes

At the top of the page is an image of every species of flamingo, below you will find some information on each species. Below this, you will find the same for the grebes.

As always, should you work in tourism or conservation of any of these species, do get in touch, we are keen to help people find you. Click on list your wild place on the homepage main menu.

American Flamingo

Found in the West Indies, northern South America (including the Galápagos Islands) and the Yucatan Peninsula. It was considered cospecifc with the greater flamingo, but they are now recognized as separate species (it is also closely related to the Chilean flamingo).

Found in the West Indies, northern South America (including the Galápagos Islands) and the Yucatan Peninsula. It was considered cospecifc with the greater flamingo, but they are now recognized as separate species (it is also closely related to the Chilean flamingo).

Formerly it was a culture icon in Southern Florida, but was largely extirpated by 1900. Having said this, there are vagrant flamingos in Florida, and these now often stay in the country worldwide.

There are 80,000-90,000 left in the wild, and there are 4 breeding colonies: in South America (in the Galápagos Islands of Ecuador, coastal Colombia and Venezuela, and northern Brazil), in the West Indies (Trinidad and Tobago, Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola (the Dominican Republic and Haiti), The Bahamas, the Virgin Islands, and the Turks and Caicos Islands), and tropical and subtropical areas of continental North America (along the northern coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, and formerly southern Florida in the United States).

Andean Flamingo

Found in the Andes mountains of South America, it is in the same genus as the James Flamingo. Indeed, the Chilean Andea and James flamingo often share nesting sites and are relatively closely related.

of South America, it is in the same genus as the James Flamingo. Indeed, the Chilean Andea and James flamingo often share nesting sites and are relatively closely related.

It is considered vulnerable to extinction with roughly 34,000 remaining in the wild, but declining over time.

As with other flamingos they are filter feeders, though what they filter can vary from algae to small fish – which they look for in shallow salty water.

They migrate between salt lakes in the summer and lower wetlands in winter – with the capacity of covering 700 miles a day.

The threat that this species faces, is generally due to human activity of mining and other changes to their habitat.

Chilean Flamingo

Closely related to  the American and greater flamingo, it is listed as near threatened in the wild with a wild population of about 200,000. Population declines are due to habitat loss and degradation, harvesting and human disturbance.

the American and greater flamingo, it is listed as near threatened in the wild with a wild population of about 200,000. Population declines are due to habitat loss and degradation, harvesting and human disturbance.

While they are only currently listed as near threatened, there is a great deal of concern about falling populations, and as such they are relatively common in zoos and there is an active breeding program..

Greater Flamingo

The greaterflamingo has the greatest of ranges of any species (as you can see from the map. While it is found down the East coast of Africa, it is also found on the northwest coast and the northern coast. It is also present in the middle east, and throughout much of Sothern Europe. Its range also extends into India. It is listed as least concern with a population between 550,000 and 680,000 with between 45,000 and 125,000 living in Europe – the Camargue is the most famous in Southern France

They are listed as least concern

James Flamingo

The James flamingo is also found on the high Andean plateau, and is closely related to the Andean Flamingo. It was thought extinct until a population was rediscovered in 1956, and the current population is thought to be around 106,000.

It is currently listed as near threatened, and on CITES appendix 2.

Lesser Flamingo![]()

Found in Sub-Saharan Africa and India. While the smallest species, it still stands 80-90cm tall. The easiest way to tell this and the greater flamingo (with overlapping range) apart is that the greater flamingo has more black on its bill.

Estimates on the number of this species range from “above” 2 million to as much as 5 million.

They generally breed in highly caustic lakes of the great rift valley in Africa, though there are places in India and a few other places as well.

They are classed as near threatened. While their choice of nesting site protects from many predators, it is still true that many flamingos are killed. From fish eagles to baboons and big cats, there are many species who will eat a flamingo if they can get hold of it.

It is well worth seeing this animal in the wild. Seeing 750,000 lesser flamingos on lake nakuru in kenya is a site that is hard to forget.

Visits to see flamingos are well worth it, and while some live in remote places, it is usually a species which is reliable. Please get in touch if you work in tourism or conservation of this species. Click on list your wild place on the home page of the website.

Tiger leaves reserve and is found on someone’s bed

- Tim

- July 21, 2019

Africa and India set up their nature reserves very differently. In Africa reserves that house lions and leopards, and animals such as this, are very large, often covering more than...

Next the Grebes

While some sites claim 22 species, my list has found that some of these were extinct (indeed, according to my list there were 3 species that have gone extinct. If there are any experts out there who notice one missing, let me know

We are eager as always to help people find places to see these birds. Do let me know if you work in wildlife tourism or run a place to stay where these birds are regularly seen. Click on list your wild place on the front page of the website.

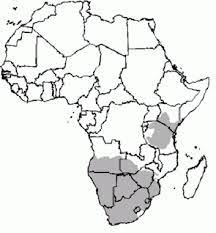

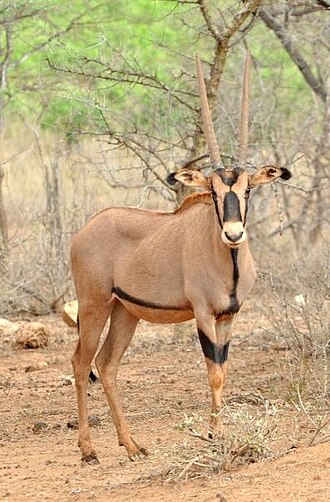

The HIrola ( also known as the Hunters hartebeest or hunters antelope) is a critically endangered species. It was named by H.C.V Hunter (a big game hunter and zoologist) in 1888. It is the only member of the genus Beatragus, and it currently has 300-500 individuals living in the wild (there are none in captivity).

The HIrola ( also known as the Hunters hartebeest or hunters antelope) is a critically endangered species. It was named by H.C.V Hunter (a big game hunter and zoologist) in 1888. It is the only member of the genus Beatragus, and it currently has 300-500 individuals living in the wild (there are none in captivity).

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species.

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species. common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

are found in a band across Africa, including areas of Eastern, Central and Western Africa.

are found in a band across Africa, including areas of Eastern, Central and Western Africa.

Impala

Impala antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

known as imbabala is a

known as imbabala is a

The bongo is a large, mostly nocturnal, forest-dwelling antelope, native to sub-Saharan Africa. Bongos are characterised by a striking reddish-brown coat, black and white markings, white-yellow stripes, and long slightly spiralled horns. It is the only member of its family in which both sexes have horns. Bongos have a complex social interaction and are found in African dense forest mosaics. They are the third-largest antelope in the world.

The bongo is a large, mostly nocturnal, forest-dwelling antelope, native to sub-Saharan Africa. Bongos are characterised by a striking reddish-brown coat, black and white markings, white-yellow stripes, and long slightly spiralled horns. It is the only member of its family in which both sexes have horns. Bongos have a complex social interaction and are found in African dense forest mosaics. They are the third-largest antelope in the world.

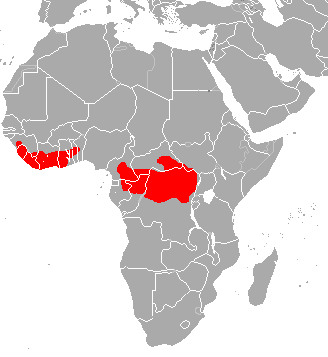

swamp-dwelling medium-sized antelope found throughout central Africa (see the map to the right. The sitatunga is mostly confined to swampy and marshy habitats. Here they occur in tall and dense vegetation as well as seasonal swamps, marshy clearings in forests, riparian thickets and mangrove swamps.

swamp-dwelling medium-sized antelope found throughout central Africa (see the map to the right. The sitatunga is mostly confined to swampy and marshy habitats. Here they occur in tall and dense vegetation as well as seasonal swamps, marshy clearings in forests, riparian thickets and mangrove swamps.

Found off the north coast of Australia (see the map to the right for a more detailed idea, the Yellow is suspected range, and the question marks designate areas which have similar attributes, but where they have never been seen) it looks very similar to the Irrawaddy dolphin, and was only recognized as a separate species in 2005.

Found off the north coast of Australia (see the map to the right for a more detailed idea, the Yellow is suspected range, and the question marks designate areas which have similar attributes, but where they have never been seen) it looks very similar to the Irrawaddy dolphin, and was only recognized as a separate species in 2005.