Would you like to list your wildlife destination on this site?

Living alongside wildlife can be complicated. A farmer will struggle to enjoy the presence of predators, even if they have not attacked his livestock.

On this website, our aim is to allow people to benefit from wildlife that they share their land with, whether this is to bring in some extra money, or to pay for protection for livestock, or whether it is the primary use (any farmers care about the environment more than city dwellers, so our aim is to make sure that where possible protecting wildlife pays – by giving them the ability to list their land for people to see the wildlife that they farm beside). Whether you live or work in one of the worlds great wildernesses or national parks, or you own wilderness on the edge of one of these (Sabi sands, one of the oldest private reserves borders the Kruger) we want to help people find you, so that you can show them all the wonderful wildlife on your land.

There are examples of each type of page to look at. Do look at the ecosystem you are located in/by is already listed as we can add further options, but will not list ecosystems more than once.

We follow a relatively simplistic booking process, where a form on the website will generate an email booking. We can also include a calendar showing your availability.

There is a link to a form for each category, as well as a further form at the bottom of the page for any questions. This form includes the ability to submit photos of your offering and the wildlife in your vicinity (both are of importance, unless your wildlife destination is already listed) . We work on a simple pricing structure, where we charge you 10% of the cost of any booking that you recieve through us. (opens in a new tab)

Do you run a lodge or campsite within a protected area?

As you can see we have listed a number of lodges in parts of Africa, but the aim of this site was to simplify wild travel and so we are keen to work with any lodge that would like to.

In order to list your property, we will need:

- Pictures of your accommodation, with information on cost and amenities

- Information on the wilderness that surrounds your property, whether it is information on a national park or reserve. (While information on the area around where you operate is always good, should your reserve already be listed, we need less here)

- Information as to what wildlife can be seen in the area, with some good pictures.

Feel free to view our lodges and reserves currently public to see what your listing can look like. If you are particular about your branding look, we are happy to put up your listing as you would like. Fill in the form at the link below.

Fill in the form in this link to list your wild place -campsite lodge or similar

Or perhaps you share your vicinity with wildlife

Whatever the reason that you own land, it will be part of a natural ecosystem and as such you are likely to have some animals that live on it with you. This can cause complications with many land uses such as farming, where predators may eat some of your livestock.

Many people will happily pay to have a chance of seeing some of these animals that can be a complication, and by utilising these visits you can make some extra money to help offset any financial losses from predation or damage to property.

This could range from South African farmers who share their land with cheetahs, to European farmers who might share their land with bears or wolves, or perhaps simply an active badgers sett in the UK.

Alternatively, you could own a restaurant where bush babies could be seen in the evening.

The possibilities are endless.

To be listed we will need:

Photos of your land with the animal/bird in question (or information on the ecosystem in which your land sits. It is worth looking at what is already up, as we will list ecosystems only once- so if someone has already listed your ecosystem, we can simply add your wildlife opportunity below.

Details of what you are offering and where it is

- Accommodation (camping or hut etc). This is particularly important if the wildlife is nocturnal or is based in a particularly remote area

- A game drive to see the wildlife at a set time.

- A restaurant, from which wildlife can be watched. This could be anything from interesting birds, lizards or indeed perhaps a resident bush baby

- Anything else that you can think of that follows along similar lines

- Information on price

Or perhaps you run a wildlife hide of some kind

For many people the only way they can have a chance of seeing many animals, particularly nocturnal ones, is by sitting in a hide. Many of my most memorable wildlife moments have been had sitting in a wildlife hide watching something unfold in front of me. This need not be on protected land, so long as the hide is not ever used for hunting.

In order to list your hide, we will need:

- Pictures of your hide with information on cost and amenities.

- Pictures of the view people will get from the hide

- Pictures of some of the wildlife that has been photographed from the hide, as well as information on frequency and anything else of interest.

See our one example currently live

Finally, we are keen to support wildlife guides, boat trips, wildlife treks, wildlife drives & other similar ecotourism.

Even in some of the wildest places on earth, it is very easy to spend weeks there and see none of the local animals.

A wildlife guide can make a big difference. Be it a trip on a boat to sea the marine life, or a car journey into a reserve nearby.

I am aware though, how often, it is hard to connect with local guides when you are visiting an area.

As such I am keen to list local guides, and the ability to book.

To be listed, I will need:

- Some information about the wildlife you often see when you take people out, preferably with some pictures (and where)

- What services you offer (are you just a guide or can you offer a place to stay as well)

- Any other information that you would like to pass on

- Pricing

Fill in the form in this link if you are a wildlife guide and would like to list your services on our website, or you run trips to see marine wildlife, or in reserves around your home.

Below is a form, which will allow you to enter all the information that you need for your page to be built. in one of these categories please fill in the form below (we aim to be a place where the whole of the wildlife tourism industry (bar any form of hunting) can advertise). Iif we do not serve your field let us know, we can either create a new section or instead fit it into another area.

Have a look at the listings we currently have to get an idea of what your listing will look like, and what we need.

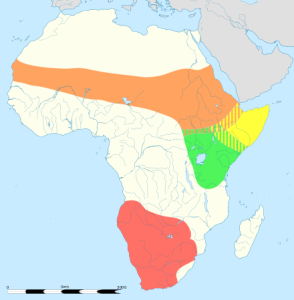

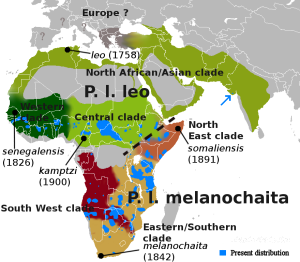

This is a map of the different Ostrich species and subspecies range

This is a map of the different Ostrich species and subspecies range

The

The

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species.

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species. common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

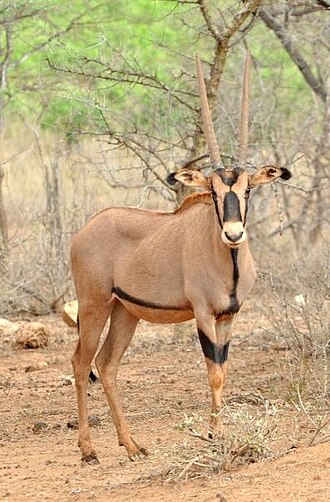

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

Impala

Impala antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

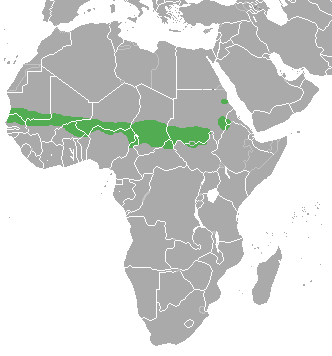

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle.

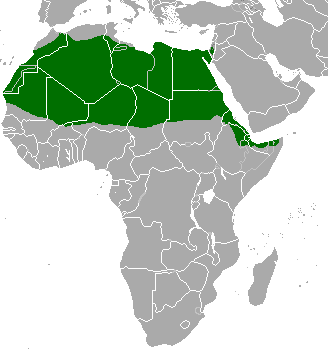

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle. Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

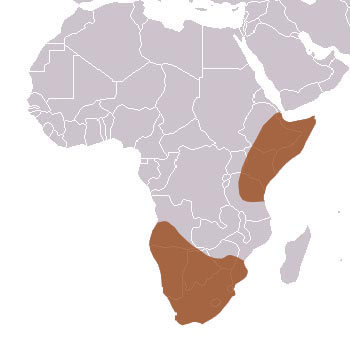

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places. A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice. The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams.

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams.  The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink. A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda. The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

Image source

Image source

Image by

Image by