Researchers have found, that reefs which have birds that fly over them, and therefore leave dropping behind, recover faster and show greater resilience after bleaching. Unfortunately, the reason that we know this, is that on islands which humans had a greater presence, we introduced rats (accidentally) and these rats ate bird eggs, and killed the birds themselves – and these islands were seen to have under 50% of the coral reef growth of those where no rats were present.

It should be noted, that, even countries like the UK do not have a native rat species. The black rat arrived with the romans, while the brown rat arrived in the 16th centuries. It is unlikely that the rat could be eradicated completely in the UK, however, on many of these far smaller islands, which are so important to bird populations, this could happen, and has occurred on a lot of small islands. Removing them from larger islands are totally different.

In many places, such as waters around the British isles (which once hosted much cold water reefs) not only are many of these birds living lower numbers, but also bottom dragging nets have been allowed to destroy large areas. We need to make sure that we map out these reefs, so that this does not happen by mistake.

Found in the West Indies, northern South America (including the Galápagos Islands) and the Yucatan Peninsula. It was considered cospecifc with the greater flamingo, but they are now recognized as separate species (it is also closely related to the Chilean flamingo).

Found in the West Indies, northern South America (including the Galápagos Islands) and the Yucatan Peninsula. It was considered cospecifc with the greater flamingo, but they are now recognized as separate species (it is also closely related to the Chilean flamingo).  of South America, it is in the same genus as the James Flamingo. Indeed, the Chilean Andea and James flamingo often share nesting sites and are relatively closely related.

of South America, it is in the same genus as the James Flamingo. Indeed, the Chilean Andea and James flamingo often share nesting sites and are relatively closely related. the American and greater flamingo, it is listed as near threatened in the wild with a wild population of about 200,000. Population declines are due to habitat loss and degradation, harvesting and

the American and greater flamingo, it is listed as near threatened in the wild with a wild population of about 200,000. Population declines are due to habitat loss and degradation, harvesting and

The

The

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species.

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species. common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

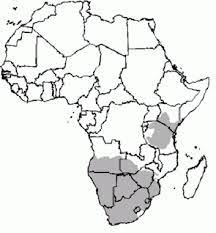

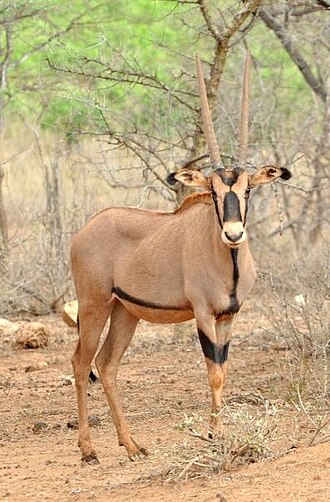

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

Impala

Impala antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

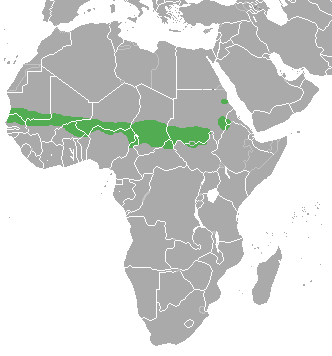

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle.

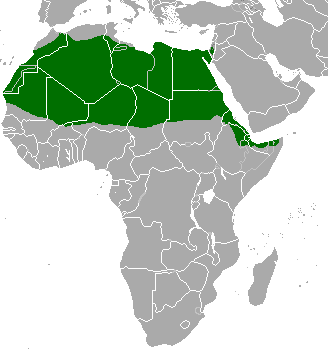

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle. Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places. A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice. The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams.

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams.  The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink. A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda. The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

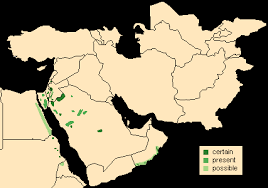

The Arabian Tahr is a species of Tahr found in eastern Arabia. They were recently moved to their own genus Arabitragus. It is the smallest Tahr species, and both genders have rear facing small horns. They have longish fur of redish brown fur, with a black stripe running down its back. They live in the Hajar Mountains in Oman and the United Arab Emirates, at evelation of up to 1800m.

The Arabian Tahr is a species of Tahr found in eastern Arabia. They were recently moved to their own genus Arabitragus. It is the smallest Tahr species, and both genders have rear facing small horns. They have longish fur of redish brown fur, with a black stripe running down its back. They live in the Hajar Mountains in Oman and the United Arab Emirates, at evelation of up to 1800m. The Barbary Sheep, is found in a variety of locations across northern Europe. Biggest populations include

The Barbary Sheep, is found in a variety of locations across northern Europe. Biggest populations include

The Bharal is found in the high Himalayas.It is split into 3 subspecies

The Bharal is found in the high Himalayas.It is split into 3 subspecies

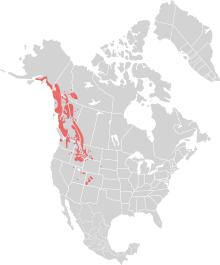

The mountain goat is sometimes referred to as the rocky mountain goat, as this is where it is found. They are incredibly sure-footed, and can often be seen seemingly defying gravity, standing on the steepest of cliffs. This appears to be a defence strategy, as lower down the mountains, brown bears and black bears, as well as

The mountain goat is sometimes referred to as the rocky mountain goat, as this is where it is found. They are incredibly sure-footed, and can often be seen seemingly defying gravity, standing on the steepest of cliffs. This appears to be a defence strategy, as lower down the mountains, brown bears and black bears, as well as  Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern

Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern

From the genus Ovibos, this map shows their range (blue is reintroductions, while red is historic range. In the long past, there were a variety of species that looked very much like this, however, not any more. The also evolved in Asia, before spreading to Europe and over to America. This map is hard to read, but they are found in Arctic areas of Alaska,

From the genus Ovibos, this map shows their range (blue is reintroductions, while red is historic range. In the long past, there were a variety of species that looked very much like this, however, not any more. The also evolved in Asia, before spreading to Europe and over to America. This map is hard to read, but they are found in Arctic areas of Alaska,  Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern India, western Bhutan and Nepal. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List, as the population is declining due to both hunting and habitat loss – with the population in its native range thought to be around 2200.

Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern India, western Bhutan and Nepal. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List, as the population is declining due to both hunting and habitat loss – with the population in its native range thought to be around 2200.

The Tibetan antelope also known as Chiru, is found in the area shown in the map to the left and is a medium-sized bovid native to the north-eastern Tibetan plateau. Most of the population live within the Chinese border, while some scatter across India and Bhutan in the high altitude plains, hill plateau and montane valley.

The Tibetan antelope also known as Chiru, is found in the area shown in the map to the left and is a medium-sized bovid native to the north-eastern Tibetan plateau. Most of the population live within the Chinese border, while some scatter across India and Bhutan in the high altitude plains, hill plateau and montane valley.

The Alpine Ibex is found throughout much of the Alps (as you can see in the map). It is also known as the Capra ibex, and the Steinbock.

The Alpine Ibex is found throughout much of the Alps (as you can see in the map). It is also known as the Capra ibex, and the Steinbock. The Bezoar ibex range is shown in the map to the left of this text. Unfortunately, they are not doing well, with only a few thousand left in the wild, primarily arouund the Caucasus.

The Bezoar ibex range is shown in the map to the left of this text. Unfortunately, they are not doing well, with only a few thousand left in the wild, primarily arouund the Caucasus.

The iberian Ibex is found throughout much eastern Iberian peninsular, with sporadic range in other parts of the peninsular. It is listed as least concern. There have been 4 subspecies identified but 2 are extinct. The surviving species are the western Iberian ibex and the Southeastern Iberian ibex (also known as the Beceite Ibex). They have an estimated combined population of 50,000 left in the wild. They are classed as least concern.

The iberian Ibex is found throughout much eastern Iberian peninsular, with sporadic range in other parts of the peninsular. It is listed as least concern. There have been 4 subspecies identified but 2 are extinct. The surviving species are the western Iberian ibex and the Southeastern Iberian ibex (also known as the Beceite Ibex). They have an estimated combined population of 50,000 left in the wild. They are classed as least concern. The Markhor is found through the green areas on the map (The markhor is a large wild Capra (goat) species native to South Asia and Central Asia, mainly within Pakistan, the Karakoram range, parts of Afghanistan, and the Himalayas. It is listed on the IUCN Red List as Near Threatened since 2015.)

The Markhor is found through the green areas on the map (The markhor is a large wild Capra (goat) species native to South Asia and Central Asia, mainly within Pakistan, the Karakoram range, parts of Afghanistan, and the Himalayas. It is listed on the IUCN Red List as Near Threatened since 2015.)

The Nubian Ibex has a relatively restricted range (as can be seen from the map to the left). The population across this area is under 5000, with the largest population in Israel (1200-1400). It is considered vulnerable. Their population has remained surprisingly stable over the last 10,000 years as the advent of domestic animals came in. Nubian Ibex, like other Ibex species take refuge on impossibly steep cliffs, and are more and more viligant the farther they are from these safe zones. This nimbleness also allows them to climb trees.

The Nubian Ibex has a relatively restricted range (as can be seen from the map to the left). The population across this area is under 5000, with the largest population in Israel (1200-1400). It is considered vulnerable. Their population has remained surprisingly stable over the last 10,000 years as the advent of domestic animals came in. Nubian Ibex, like other Ibex species take refuge on impossibly steep cliffs, and are more and more viligant the farther they are from these safe zones. This nimbleness also allows them to climb trees. The Siberian ibex is also known using regionalized names including Altai ibex, Asian ibex, Central Asian ibex, Gobi ibex, Himalayan ibex, Mongolian ibex or Tian Shan ibex.

The Siberian ibex is also known using regionalized names including Altai ibex, Asian ibex, Central Asian ibex, Gobi ibex, Himalayan ibex, Mongolian ibex or Tian Shan ibex.

The Walia Ibex does not have a large range (see it to the left). It is classed as vulnerable and numbers 450-500 in the wild, living in the Simien mountains of Ethiopia.

The Walia Ibex does not have a large range (see it to the left). It is classed as vulnerable and numbers 450-500 in the wild, living in the Simien mountains of Ethiopia. The west Asian Ibex (often referred to as wild goat) has the range shown on the left. It inhabits forests, shrubland and rocky areas across this range. It is classed as near threatened, largely as a result of degradation and destruction of their habitat. It is thought to be the ancestor of the domestic goat.

The west Asian Ibex (often referred to as wild goat) has the range shown on the left. It inhabits forests, shrubland and rocky areas across this range. It is classed as near threatened, largely as a result of degradation and destruction of their habitat. It is thought to be the ancestor of the domestic goat.

Native to this region of north America, there are 3 recognized subspecies, though in the past 7 were recognized.

Native to this region of north America, there are 3 recognized subspecies, though in the past 7 were recognized.

Also known as thin horn sheep, there are only 2 subspecies, being the nominate subspecies and the stone sheep.

Also known as thin horn sheep, there are only 2 subspecies, being the nominate subspecies and the stone sheep.

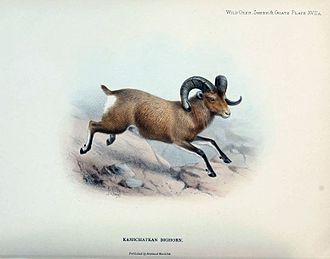

Also known as the Siberian bighorn sheep. They are

Also known as the Siberian bighorn sheep. They are

Also known as arkars, shapo, or shapu, is a wild sheep native to Central and South Asia. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and its range map is to the left.

Also known as arkars, shapo, or shapu, is a wild sheep native to Central and South Asia. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and its range map is to the left. The chamois or Alpine chamois is a species of goat-antelope native to the mountains in Southern Europe, from the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Apennines, the Dinarides, the Tatra to the Carpathian Mountains, the Balkan Mountains, the

The chamois or Alpine chamois is a species of goat-antelope native to the mountains in Southern Europe, from the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Apennines, the Dinarides, the Tatra to the Carpathian Mountains, the Balkan Mountains, the

The Pyrenean chamois is a goat-antelope that lives in the Pyrenees and Cantabrian Mountains of Spain,

The Pyrenean chamois is a goat-antelope that lives in the Pyrenees and Cantabrian Mountains of Spain,  Also known as a Thar, It is the official state animal of the Indian state of Mizoram. It has at various times been considered a separate species in its own right. At the moment, it is thought to be a subspecies of the mainland Serow, however it has moved back and forwards in recent years, so we will list them all.

Also known as a Thar, It is the official state animal of the Indian state of Mizoram. It has at various times been considered a separate species in its own right. At the moment, it is thought to be a subspecies of the mainland Serow, however it has moved back and forwards in recent years, so we will list them all.

It is found in dense woodland in

It is found in dense woodland in  As can be seen, the Mainland Serow includes the whole range of Himalayan Serow, and both species look very similar. It has already declined by 30% in the last 3 generations, and is classed as vulnerable. This is at least, in part, a result of deforestation and expansion of the palm oil industry. Unfortunately, there is no estimate at the current time, for the size of this wild population.

As can be seen, the Mainland Serow includes the whole range of Himalayan Serow, and both species look very similar. It has already declined by 30% in the last 3 generations, and is classed as vulnerable. This is at least, in part, a result of deforestation and expansion of the palm oil industry. Unfortunately, there is no estimate at the current time, for the size of this wild population.

Also known as the Burmese red serow, the range of this species (or possibly subspecies, as it has at time been thought of as a subspecies of the Sumatran Serow) is shown in the map to the left.

Also known as the Burmese red serow, the range of this species (or possibly subspecies, as it has at time been thought of as a subspecies of the Sumatran Serow) is shown in the map to the left. This map shows the range of all serow species (or subspecies) the Southern Serow, inhabits the grey range that is lowest on the map. They are classed as vulnerable to extinction. There is no estimate for them across their whole range, but the population of Malaysia is thought to be between 500-750.

This map shows the range of all serow species (or subspecies) the Southern Serow, inhabits the grey range that is lowest on the map. They are classed as vulnerable to extinction. There is no estimate for them across their whole range, but the population of Malaysia is thought to be between 500-750.

The Taiwanese Serow (also known as the Formosan Serow) lives on the island of Taiwan. It is classed as least concern, but there is no concrete estimate on its wild numbers. Generally browsers, they are very shy, and are usually not seen, merely known of there prescense from their droppings.

The Taiwanese Serow (also known as the Formosan Serow) lives on the island of Taiwan. It is classed as least concern, but there is no concrete estimate on its wild numbers. Generally browsers, they are very shy, and are usually not seen, merely known of there prescense from their droppings. Also known as the grey long-tailed goral or central Chinese goral, is a species of goral, a small goat-like ungulate, native to mountainous regions of Myanmar, China, India,

Also known as the grey long-tailed goral or central Chinese goral, is a species of goral, a small goat-like ungulate, native to mountainous regions of Myanmar, China, India,

The Himalayan goral also known as the gray goral, is a bovid species native to the Himalayas. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List because the population is thought to be declining significantly due to habitat loss and hunting for meat. It is also on CITES appendix 1 which bans trade. There is no estimate on numbers.

The Himalayan goral also known as the gray goral, is a bovid species native to the Himalayas. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List because the population is thought to be declining significantly due to habitat loss and hunting for meat. It is also on CITES appendix 1 which bans trade. There is no estimate on numbers. This species is not living in the best place for active conservation, and it is thought taht there may be only 250 left in the wild. Much of this species population live along the borders of North Korea. In some ways this is positive, as the way the country has been run, means that animals lost elsewhere still thrive here (there is possibly still tigers in north korea). Apart from during the rut when males roam far and wide, each individual tends to stay within a 100 acre area.

This species is not living in the best place for active conservation, and it is thought taht there may be only 250 left in the wild. Much of this species population live along the borders of North Korea. In some ways this is positive, as the way the country has been run, means that animals lost elsewhere still thrive here (there is possibly still tigers in north korea). Apart from during the rut when males roam far and wide, each individual tends to stay within a 100 acre area.

The red goral is considered vulnerable to extinction (a better situation than many other goral species (or perhaps subspecies). The upper bound for its population is thought to be around 10,000, though it is thought by many, that the population is likely to be very much lower.

The red goral is considered vulnerable to extinction (a better situation than many other goral species (or perhaps subspecies). The upper bound for its population is thought to be around 10,000, though it is thought by many, that the population is likely to be very much lower.