Both ostrich species Combined PaleoNeolithic photo credit Diego Delso&Ninara

Ostrich

Common Ostrich

Somali Ostrich

The common ostrich is found across a large part of the African Continent. Until 1919 there was a fourth subspecies of the common ostrich which was found across much of the Arabian Peninsular. It was completely extinct in the wild by 1972. They have now been reintroduced to Israel, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and United Arab Emirates – though it is hard to find accurate figures for how many are found there now. (Do get in touch if you operate a reserve with these birds present, we would love to help people find you).

As you can see, the other African subspecies are still going.

The Somali Ostrich was only recognized as a separate species back in 2014, having been thought to be a subspecies until them.

A report to the IUCN in 2006 believed that this ostrich was common in central and southern Somalia until 1970-80. However, following the breakdown in the country, it is not surprising that conservation took back-stage, and it is questionable as to whether any remain (in the horn of africa).

In Kenya it is farmed for meat, feathers and eggs.

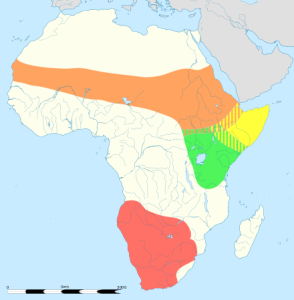

This is a map of the different Ostrich species and subspecies range

This is a map of the different Ostrich species and subspecies range

- The yellow area, shows the range of the Somali Ostrich – Now recognized as a separate species.

- The green area shows the range of the Massai Ostrich – while this population is listed as least concern, its numbers are in decline

- The red is the South African Ostrich, this is generally secure, though only found within reserves.

- The Orange is the range of the North African Ostrich: classed as critically endangered, it is only found in 6 of the 18 countries it originally roamed. It is the largest and heaviest subspecies. The countries it is still found in include fragmented pockets of Cameroon, Chad, Central African Republic and Senegal. They have also been reintroduced into Chad, Morocco and in 2014 (127 years after being lost) Tunisia. They were reintroduced to Saudi Arabia in the Mahazat as-Sayd Protected Area in 1994 and this population has done well with around 90-100 now living within this reserve

There is thought to be approximately 150,000 ostrich left in the wild. Having said this, like other large species, they are prone to local extinction. The best way to see these in the wild are to head to reserves where they still exist.

Unfortunately, they are not easy to look after – in smaller reserves with large predators, they can be hunted and face local extinction. As such, while there are other reserves where they hang on, the majority of their remaining population are split between big reserves like the Kruger and the Serengeti, and small reserves like the Cape point national park in South Africa (this reserve is only 77.5 square km, or around 30 square miles and was in the past a big 5 nature reserve. Now, only the cape leopard is present and this is very rarely seen.

If you wish to see the Ostrich look in our list of wild places. Kruger, Okavango and the Serengeti all have ostrich (in Kruger you need to look in the more sparsely area in the north of the park).

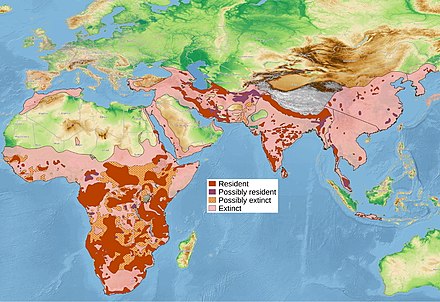

50 years ago, Africa was estimated to have 700,000 the current number is nearer to 50,000 (the 700,000 figure came from a study in 1988, estimates vary widely, when I have written all my African leopard pages, I will give an estimate based on all the country estimates (it should be noted, however that this may be no more accurate). This is not evenly spread, such that while 34 countries are thought to still host them. It should be noted, that the so called Barbary leopard is included in this subspecies. While there is still much debate (not least the suggestion that the Sahara might have stopped gene from from the Barbary region to the rest of Africa. In a similar way, there is discussion on a variety of different populations of leopards, but these will not get their own tab, until they are declared as recognized subspecies (there was, at one time as many as 37 claimed different subspecies of leopard spread across Africa and Asia, many were lost, when the genetic differences were found to be so small).

50 years ago, Africa was estimated to have 700,000 the current number is nearer to 50,000 (the 700,000 figure came from a study in 1988, estimates vary widely, when I have written all my African leopard pages, I will give an estimate based on all the country estimates (it should be noted, however that this may be no more accurate). This is not evenly spread, such that while 34 countries are thought to still host them. It should be noted, that the so called Barbary leopard is included in this subspecies. While there is still much debate (not least the suggestion that the Sahara might have stopped gene from from the Barbary region to the rest of Africa. In a similar way, there is discussion on a variety of different populations of leopards, but these will not get their own tab, until they are declared as recognized subspecies (there was, at one time as many as 37 claimed different subspecies of leopard spread across Africa and Asia, many were lost, when the genetic differences were found to be so small).

The number of Indian leopards in the wild is a worryingly low number. Some places suggest around 9500, while others suggest 12,000-14,000 (remember that the area of

The number of Indian leopards in the wild is a worryingly low number. Some places suggest around 9500, while others suggest 12,000-14,000 (remember that the area of

In 2008, the size of this subspecies left in the wild was thought to be between 45 and 200. As such, it is perhaps not surprising that this subspecies has been critically endangered since 1996.

In 2008, the size of this subspecies left in the wild was thought to be between 45 and 200. As such, it is perhaps not surprising that this subspecies has been critically endangered since 1996.

Caucasian (also called Persian) Leopard)

Caucasian (also called Persian) Leopard)

Only described in 1956, they are relatively similar to the Indian Leopard, and were thought to be part of that subspecies until then. There are only 800 of this subspecies of leopard, and they were listed as vulnerable in 2020, and unfortunately it is thought to still be declining. It is thought, that as a result of being the apex predator on the island, they have got bigger.

Only described in 1956, they are relatively similar to the Indian Leopard, and were thought to be part of that subspecies until then. There are only 800 of this subspecies of leopard, and they were listed as vulnerable in 2020, and unfortunately it is thought to still be declining. It is thought, that as a result of being the apex predator on the island, they have got bigger.

Records from before 1930 suggest that this species of Leopard used to live near Beijing and in the mountains to the North-west. The wild population is estimated at around 110, so is one of the more endangered leopard species in the world. It is thought that this population and the Amur Leopard species were connected until just a few hundred years ago. As such, it may well be possible to boost genetic variability if that were to become necessary.

Records from before 1930 suggest that this species of Leopard used to live near Beijing and in the mountains to the North-west. The wild population is estimated at around 110, so is one of the more endangered leopard species in the world. It is thought that this population and the Amur Leopard species were connected until just a few hundred years ago. As such, it may well be possible to boost genetic variability if that were to become necessary.

Like many cats – both big and lesser cats, they have rare colourings. These are not separate species, instead they are either melanistic, or albino.

Like many cats – both big and lesser cats, they have rare colourings. These are not separate species, instead they are either melanistic, or albino.