2. Reduncinae - Rhebok, Reedbuck, Waterbuck

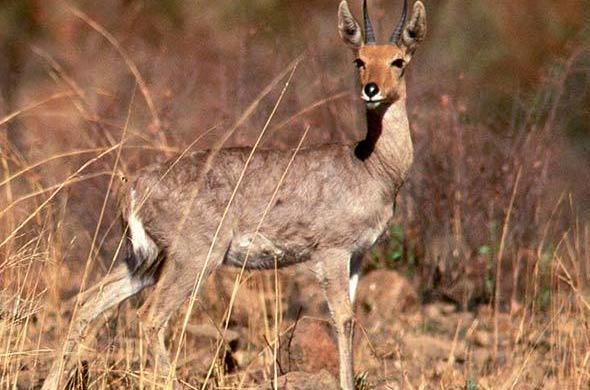

Bohor Reedbuck

The bohor reedbuck is an antelope native to central Africa.

The head-and-body length of this medium-sized antelope is typically between 100–135 cm. Females are smaller. This sturdily built antelope has a yellow to grayish brown coat. Only the males possess horns which measure about 25–35 cm long. There are 5 subspecies:

- R. r. bohor Rüppell, 1842: Also known as the Abyssinian bohor reedbuck. It occurs in southwestern, western and central Ethiopia, and Blue Nile (Sudan).

- R. r. cottoni (W. Rothschild, 1902): It occurs in the Sudds (Southern Sudan), northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and probably in northern Uganda.

- R. r. nigeriensis (Blaine, 1913): This subspecies occurs in Nigeria, northern Cameroon, southern Chad and Central African Republic.

- R. r. redunca (Pallas, 1767): Its range extends from Senegal east to Togo. It inhabits the northern savannas of Africa.

- R. r. wardi (Thomas, 1900): Found in Uganda, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and eastern Africa.

Mountain Reedbuck

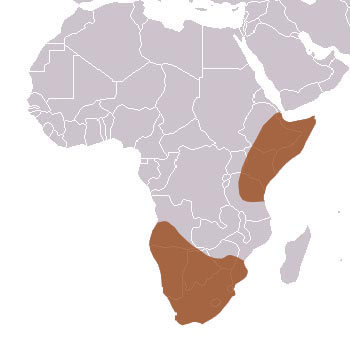

The mountain reedbuck has 3 subspecies.  The western mountain reedbuck only has 450 individuals still living wild, (shown on the map in red) also known as the Adamwa mountain reedbuck which is restricted to the highlands of Cameroon. The Eastern mountain reedbuck (or Chanlers) has 2900 wild individuals, is found in parts of Kenya and Ethiopia. The Southern moutnain reedbuck, blue, (33,000) is found in the Drakensburg mountains of South Africa.

The western mountain reedbuck only has 450 individuals still living wild, (shown on the map in red) also known as the Adamwa mountain reedbuck which is restricted to the highlands of Cameroon. The Eastern mountain reedbuck (or Chanlers) has 2900 wild individuals, is found in parts of Kenya and Ethiopia. The Southern moutnain reedbuck, blue, (33,000) is found in the Drakensburg mountains of South Africa.

Southern Reedbuck

The Southern, or common  Reedbuck is found in Southern Africa. It is a midsized antelope, standing 134-167cm tall

Reedbuck is found in Southern Africa. It is a midsized antelope, standing 134-167cm tall

It was described in 1785 by Pieter Boddaert. Southern reedbucks live in pairs or alone, though occasionally they will form herds of up to 20. They prefer to lie in grass or reed beds in the heat of the day and feed during sunrise and sunset, or sometimes even at night. Old reedbucks are permanently territorial, with territories around 35-60 hectares, and generally live with a single female, preventing contact with rival males. Females and young males perform an ‘appeasement dance’ for older males. Within this territory, it is active all the time in summer, but it is nocturnal in the wet season. It regularly uses paths to reach good sites to rest, graze, and drink water. They are hunted by all the top predators in the area, including Lion, Leopard, Cheetah hyena and wild dog, as well as animals like snakes.

They are easily hunted, and combined with loss of territory to human expansion, the population is down. About 60% occur in protected reserves, but in some countries like Gabon and the DRC are though to almost be locally extinct.

Kob

The puku is a mid-sized antelope found in wet grasslands in Southern Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and more concentrated in the Okavango Delta in Botswana.

Nearly one-third of all puku are found in protected areas, zoos, and national parks due to their diminishing habitat (though this still leaves 2/3 of Puku living outside all protected areas.

Red Lechwe

Red Lechewe is a species of antelope found in the south of eastern African. The red lechwe is native to Botswana, Zambia, southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, northeastern Namibia, and eastern Angola, especially in the Okavango Delta, Kafue Flats, and Bangweulu Wetlands. They are found in shallow water, and have a substance on their legs which allows them to run pretty fast. Total population is around 160,000

is a species of antelope found in the south of eastern African. The red lechwe is native to Botswana, Zambia, southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, northeastern Namibia, and eastern Angola, especially in the Okavango Delta, Kafue Flats, and Bangweulu Wetlands. They are found in shallow water, and have a substance on their legs which allows them to run pretty fast. Total population is around 160,000

Four subspecies of the lechwe have been recognized

- Common red lechwe (Gray, 1850) – Widely distributed in the wetlands of Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia and Zambia. (80,000)

- Kafue Flats lechwe (Haltenorth, 1963) – It is confined within the Kafue Flats (seasonally inundated flood-plain on the Kafue River, Zambia). (28,000)

- † Roberts’ lechwe (Rothschild, 1907) – Formerly found in northeastern Zambia, now extinct. Also called the Kawambwa lechwe.

- Black lechwe (Kobus leche smithemani) (Lydekker, 1900) – Found in the Bangweulu region of Zambia. (50,000)

In addition, the Upemba lechwe (1000) and the extinct Cape lechwe are also considered subspecies by some authorities. Although related and sharing the name “lechwe”, the Nile lechwe (below) is consistently recognized as a separate species.

Nile Lechwe

The Nile lechwe or Mrs Gray’s lechwe is an endangered species of antelope found in swamps and grasslands in South Sudan and Ethiopia.

The Nile lechwe or Mrs Gray’s lechwe is an endangered species of antelope found in swamps and grasslands in South Sudan and Ethiopia.

Nile lechwe can visually signal and vocalize to communicate with each other. They rear high in the air in front of their opponents and turn their heads to the side while displaying. Females are quite loud, making a toad-like croaking when moving. Known predators are humans, lions, crocodiles, cheetahs, wild dogs, hyenas and leopards. They flee to water if disturbed, but females defend their offspring from smaller predators by direct attack, mainly kicking. Nile lechwe are crepuscular, active in the early morning and late afternoon. They gather in herds of up to 50 females and one male or in smaller all-male herds. They divide themselves into three social groups: females and their new offspring, bachelor males, and mature males with territories. A males with territory sometimes allows a bachelor male into his territory to guard the region and not to copulate. They are sexually mature at 2.

Nile lechwe feed on succulent grasses and water plants. They have the special capability to wade in shallow waters and swim in deeper waters, and may feed on young leaves from trees and bushes, rearing up to reach this green vegetation. Nile lechwe are also found in marshy areas, where they eat aquatic plants. Around 32,000 and are classed as endangered

Puku

The puku is a medium-sized antelope found in wet grasslands in southern Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and more concentrated in the Okavango Delta in Botswana. Nearly one-third of all puku are found in protected areas, zoos, and national parks due to their diminishing habitat (the issue here, is that these 2/3 are clearly at danger of disappearing if humans change their behaviour. They are currenly listed as not threatened

The puku is a medium-sized antelope found in wet grasslands in southern Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and more concentrated in the Okavango Delta in Botswana. Nearly one-third of all puku are found in protected areas, zoos, and national parks due to their diminishing habitat (the issue here, is that these 2/3 are clearly at danger of disappearing if humans change their behaviour. They are currenly listed as not threatened

Two subspecies exist:

- Senga Puku

- Southern Puku

Waterbuck

The waterbuck  is a large antelope found widely in sub-Saharan Africa.It was first described by Irish naturalist William Ogilby in 1833.

is a large antelope found widely in sub-Saharan Africa.It was first described by Irish naturalist William Ogilby in 1833.

Its 13 subspecies are grouped under two varieties: the common or ellipsiprymnus waterbuck and the defassa waterbuck. The head-and-body length is typically between 177 and 235cm and the typical height is between 120 and 136cm. In this antelope, males are taller and heavier than females. Males reach roughly 127 cm at the shoulder, while females reach 119cm. Males typically weigh 198–262 kg and females 161–214 kg. Their coat colour varies from brown to grey. The long, spiral horns, present only on males, curve backward, then forward, and are 55–99 cm long. Waterbucks are rather sedentary in nature. As gregarious animals, they may form herds consisting of six to 30 individuals. These groups are either nursery herds with females and their offspring or bachelor herds. Males start showing territorial behaviour from the age of 5 years, but are most dominant from the six to nine. The waterbuck cannot tolerate dehydration in hot weather, and thus inhabits areas close to sources of water. Predominantly a grazer, the waterbuck is mostly found on grassland. In equatorial regions, breeding takes place throughout the year, but births are at their peak in the rainy season. The gestational period lasts 7–8 months, followed by the birth of a single calf.

Waterbucks inhabit scrub and savanna areas along rivers, lakes, and valleys. Due to their requirement for grasslands and water, waterbucks have a sparse ecotone distribution. The IUCN lists the waterbuck as being of least concern. More specifically, the common waterbuck is listed as of least concern. while the defassa waterbuck is near threatened. The population trend for both is downwards, especially that of the defassa, with large populations being eliminated from certain habitats because of poaching and human disturbance.

The common waterbuck is listed as least concern, while the Defassa is listed as near threatened. Only 60% of this subspecies population is in protected areas, so it could get worse, if they are lost.

The aardwolf is the smallest member of the Hyaenidae family, as you can see from the map, it is a species with two separated populations, one in East Africa and one in Southern Africa. It is insectivorous, and exclusively nocturnal, and is generally thought of as one of the harder animals to see in the wild. If incredibly lucky, you can see them feeding alongside Aardvarks, and even Pangolins, but this is rare. They favour open dry plains and savannahs.

The aardwolf is the smallest member of the Hyaenidae family, as you can see from the map, it is a species with two separated populations, one in East Africa and one in Southern Africa. It is insectivorous, and exclusively nocturnal, and is generally thought of as one of the harder animals to see in the wild. If incredibly lucky, you can see them feeding alongside Aardvarks, and even Pangolins, but this is rare. They favour open dry plains and savannahs.