1. Tragelaphini - spiral-horned antelope

Bushbuck

The Cape bushbuck , also known as imbabala is a common, medium-sized and a widespread species of antelope in sub-Saharan Africa. It is found in a wide range of habitats, such as rain forests, montane forests, forest-savanna mosaic, savanna, bushveld, and woodland. Its stands around 90 cm at the shoulder and weigh from 45 to 80 kg. They are generally solitary, territorial browsers.

known as imbabala is a common, medium-sized and a widespread species of antelope in sub-Saharan Africa. It is found in a wide range of habitats, such as rain forests, montane forests, forest-savanna mosaic, savanna, bushveld, and woodland. Its stands around 90 cm at the shoulder and weigh from 45 to 80 kg. They are generally solitary, territorial browsers.

Although rarely seen, as it spends most of its time deep in the thick bush, there are around 1 million in Africa

Common Eland

The common eland (southern eland or eland antelope) is a large-sized savannah and plains antelope from East and Southern Africa. An adult male is around 1.6 m tall at the shoulder (females are 20 cm shorter) and can weigh up to 942 kg with a typical range of 500–600 kg. Only the giant eland is (on average bigger). It was described by Peter Simon Pallas in 1766. Population of 136,000, can form herds of 500

The common eland (southern eland or eland antelope) is a large-sized savannah and plains antelope from East and Southern Africa. An adult male is around 1.6 m tall at the shoulder (females are 20 cm shorter) and can weigh up to 942 kg with a typical range of 500–600 kg. Only the giant eland is (on average bigger). It was described by Peter Simon Pallas in 1766. Population of 136,000, can form herds of 500

Giant Eland

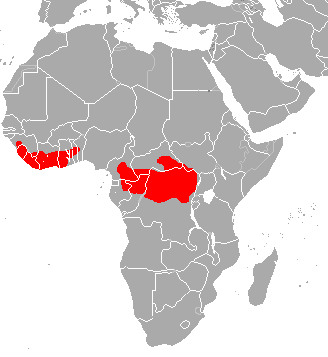

The giant eland, (also known as Lord Derby’s eland and greater eland) is an open-forest and savanna antelope.

The giant eland, (also known as Lord Derby’s eland and greater eland) is an open-forest and savanna antelope.

It was described in 1847 by John Edward Gray. The giant eland is the largest species of antelope, with a body length ranging from 220–290 cm (87–114 in). There are two subspecies: T. d. derbianus and T. d. gigas.

The giant eland is a herbivore, living in small mixed gender herds consisting of 15–25 members. Giant elands have large home ranges. They can run at up to 70 km/h. They mostly inhabit broad-leafed savannas and woodlands and are listed as vulnerable and have a wild population of 12,000-14,000

Greater Kudu

The greater kudu is a large woodland antelope, you can see its distribution on the map. Despite occupying such widespread territory, they are sparsely populated in most areas due to declining habitat, deforestation, and poaching.

The greater kudu is a large woodland antelope, you can see its distribution on the map. Despite occupying such widespread territory, they are sparsely populated in most areas due to declining habitat, deforestation, and poaching.

The spiral horns are impressive, and grow at one curl every 3 years – they are fully grown at 7 and a half years with 2 and a half turns. Three subspecies have been agreed (one described has been rejected) :

- T. s. strepsiceros – southern parts of the range from southern Kenya to Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa

- T. s. chora – northeastern Africa from northern Kenya through Ethiopia to eastern Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea

- T. s. cottoni – Chad and western Sudan

Lesser Kudu

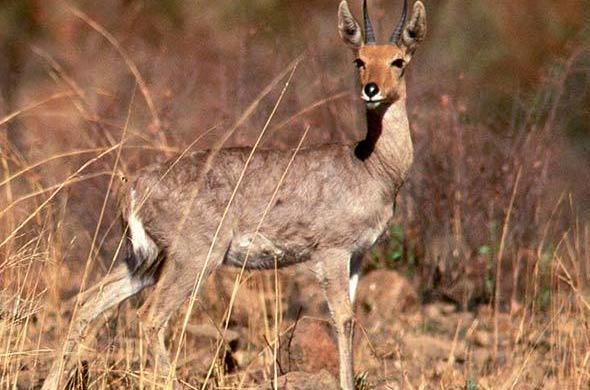

The lesser kudu is a medium-sized bushland antelope found in East Africa. It was first scientifically described by English zoologist Edward Blyth (1869).It stands around 90 cm at the shoulder and weigh from 45 to 80 kg. They are generally solitary, territorial browsers.

lesser kudu is a medium-sized bushland antelope found in East Africa. It was first scientifically described by English zoologist Edward Blyth (1869).It stands around 90 cm at the shoulder and weigh from 45 to 80 kg. They are generally solitary, territorial browsers.

While currently rated not threatened, its population is decreasing. It currently stands at 100,000, but it is loosing territory to humans

Common Bongo (and mountain or Eastern Bongo)

The bongo is a large, mostly nocturnal, forest-dwelling antelope, native to sub-Saharan Africa. Bongos are characterised by a striking reddish-brown coat, black and white markings, white-yellow stripes, and long slightly spiralled horns. It is the only member of its family in which both sexes have horns. Bongos have a complex social interaction and are found in African dense forest mosaics. They are the third-largest antelope in the world.

The bongo is a large, mostly nocturnal, forest-dwelling antelope, native to sub-Saharan Africa. Bongos are characterised by a striking reddish-brown coat, black and white markings, white-yellow stripes, and long slightly spiralled horns. It is the only member of its family in which both sexes have horns. Bongos have a complex social interaction and are found in African dense forest mosaics. They are the third-largest antelope in the world.

The Common (western or lowland bongo), faces an ongoing population decline, and the IUCN considers it to be Near Threatened. The picture to the right is of a common bongo. Beneath that is a short video about a common bongo. The mountain bongo, which is discussed below, has a video below the common bongo.

The mountain bongo (or eastern) of Kenya, has a coat even more vibrant than the common version. The mountain bongo is only found in the wild in a few mountain regions of central Kenya. This bongo is classified by the IUCN as Critically Endangered (where it breeds readily). (this is not on the map above). Only 100 live wild, split between 4 areas of Kenya

T

The Nyala is a spiral horned species found in Southern Africa. The nyala is mainly active in the early morning and the late afternoon. It generally browses during the day if temperatures are 20–30 °C and during the night in the rainy season. The nyala feeds upon foliage, fruits and grasses, and requires sufficient fresh water. It is a very shy animal, and prefers water holes to the river bank. Not territorial, they are very cautious creatures. They live in single-sex or mixed family groups of up to 10 individuals, but old males live alone. They inhabit thickets within dense and dry savanna woodlands. The main predators of the nyala are lion, leopard and African wild dog, while baboons and raptorial birds prey on juveniles. Males and females are sexually mature at 18 and 11–12 months of age respectively, though they are socially immature until five years old. They have one calf after 7 months of gestation. Its population is stable, with the greatest threat coming from habitat loss as humans expand. There are thought to be 36500 and the population is stable.

The Nyala is a spiral horned species found in Southern Africa. The nyala is mainly active in the early morning and the late afternoon. It generally browses during the day if temperatures are 20–30 °C and during the night in the rainy season. The nyala feeds upon foliage, fruits and grasses, and requires sufficient fresh water. It is a very shy animal, and prefers water holes to the river bank. Not territorial, they are very cautious creatures. They live in single-sex or mixed family groups of up to 10 individuals, but old males live alone. They inhabit thickets within dense and dry savanna woodlands. The main predators of the nyala are lion, leopard and African wild dog, while baboons and raptorial birds prey on juveniles. Males and females are sexually mature at 18 and 11–12 months of age respectively, though they are socially immature until five years old. They have one calf after 7 months of gestation. Its population is stable, with the greatest threat coming from habitat loss as humans expand. There are thought to be 36500 and the population is stable.

Mountain Nyala

The mountain Nyala (also known as the Balbok) is a large antelope found in high altitude woodlands in just a small part of central Ethiopia. The coat is grey to brown, marked with two to five poorly defined white strips extending from the back to the underside, and a row of six to ten white spots. White markings are present on the face, throat and legs as well. Males have a short dark erect crest, about 10 cm (3.9 in) high, running along the middle of the back. Only males possess horns.

The mountain Nyala (also known as the Balbok) is a large antelope found in high altitude woodlands in just a small part of central Ethiopia. The coat is grey to brown, marked with two to five poorly defined white strips extending from the back to the underside, and a row of six to ten white spots. White markings are present on the face, throat and legs as well. Males have a short dark erect crest, about 10 cm (3.9 in) high, running along the middle of the back. Only males possess horns.

The mountain nyala are shy and elusive towards human beings. They form small temporary herds. Males are not territorial. Primarily a browser. They will grazing occasionally. Males and females are sexually mature at 2 years old.. Gestation lasts for eight to nine months, after which a single calf is born. The lifespan of a mountain nyala is around 15 to 20 years.

Found in mountain woodland -between 3000m and 4000m. Human settlement and large livestock population have forced the animal to occupy heath forests at an altitude of above 3,400 m (11,200 ft). Mountain nyala are endemic to the Ethiopian highlands east of the Rift Valley. As much as half of the population live within 200 square km (77 sq mi) area of Gaysay, in the northern part of the Bale Mountains National Park. The mountain nyala has been classified under the Endangered category of the (IUCN). Their influence on Ethiopian culture is notable, with the mountain nyala being featured on the obverse of Ethiopian ten cents coins.

Sitatunga Antelope

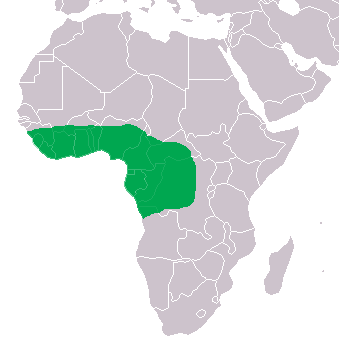

The sitatunga (or marshbuck)is a  swamp-dwelling medium-sized antelope found throughout central Africa (see the map to the right. The sitatunga is mostly confined to swampy and marshy habitats. Here they occur in tall and dense vegetation as well as seasonal swamps, marshy clearings in forests, riparian thickets and mangrove swamps.

swamp-dwelling medium-sized antelope found throughout central Africa (see the map to the right. The sitatunga is mostly confined to swampy and marshy habitats. Here they occur in tall and dense vegetation as well as seasonal swamps, marshy clearings in forests, riparian thickets and mangrove swamps.

The scientific name of the sitatunga is Tragelaphus spekii. The species was first described by the English explorer John Hanning Speke in 1863.

It is listed as least concern with 170,000-200,000, and are found in 25 countries. However 40% live outside reserves, so the situation could get worse fast.

Note: these animals have been dealt with in less detail than others. Should you be interested in finding out if I have written on these animals or what exactly I said, you can find a list of articles about each below its information.

Reedbuck is found in Southern Africa. It is a midsized

Reedbuck is found in Southern Africa. It is a midsized

The Nile lechwe or Mrs Gray’s lechwe is an endangered species of antelope found in swamps and grasslands in South Sudan and Ethiopia.

The Nile lechwe or Mrs Gray’s lechwe is an endangered species of antelope found in swamps and grasslands in South Sudan and Ethiopia.

The puku is a medium-sized antelope found in wet grasslands in southern Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and more concentrated in the Okavango Delta in Botswana. Nearly one-third of all puku are found in protected areas, zoos, and national parks due to their diminishing habitat (the issue here, is that these 2/3 are clearly at danger of disappearing if humans change their behaviour. They are currenly listed as not threatened

The puku is a medium-sized antelope found in wet grasslands in southern Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and more concentrated in the Okavango Delta in Botswana. Nearly one-third of all puku are found in protected areas, zoos, and national parks due to their diminishing habitat (the issue here, is that these 2/3 are clearly at danger of disappearing if humans change their behaviour. They are currenly listed as not threatened