1. Tragelaphini - spiral-horned antelope

Bushbuck

The Cape bushbuck , also known as imbabala is a common, medium-sized and a widespread species of antelope in sub-Saharan Africa. It is found in a wide range of habitats, such as rain forests, montane forests, forest-savanna mosaic, savanna, bushveld, and woodland. Its stands around 90 cm at the shoulder and weigh from 45 to 80 kg. They are generally solitary, territorial browsers.

known as imbabala is a common, medium-sized and a widespread species of antelope in sub-Saharan Africa. It is found in a wide range of habitats, such as rain forests, montane forests, forest-savanna mosaic, savanna, bushveld, and woodland. Its stands around 90 cm at the shoulder and weigh from 45 to 80 kg. They are generally solitary, territorial browsers.

Although rarely seen, as it spends most of its time deep in the thick bush, there are around 1 million in Africa

Common Eland

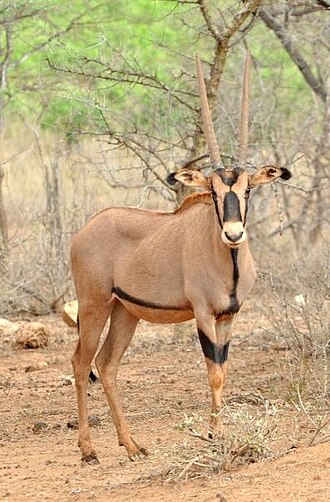

The common eland (southern eland or eland antelope) is a large-sized savannah and plains antelope from East and Southern Africa. An adult male is around 1.6 m tall at the shoulder (females are 20 cm shorter) and can weigh up to 942 kg with a typical range of 500–600 kg. Only the giant eland is (on average bigger). It was described by Peter Simon Pallas in 1766. Population of 136,000, can form herds of 500

The common eland (southern eland or eland antelope) is a large-sized savannah and plains antelope from East and Southern Africa. An adult male is around 1.6 m tall at the shoulder (females are 20 cm shorter) and can weigh up to 942 kg with a typical range of 500–600 kg. Only the giant eland is (on average bigger). It was described by Peter Simon Pallas in 1766. Population of 136,000, can form herds of 500

Giant Eland

The giant eland, (also known as Lord Derby’s eland and greater eland) is an open-forest and savanna antelope.

It was described in 1847 by John Edward Gray. The giant eland is the largest species of antelope, with a body length ranging from 220–290 cm (87–114 in). There are two subspecies: T. d. derbianus and T. d. gigas.

The giant eland is a herbivore, living in small mixed gender herds consisting of 15–25 members. Giant elands have large home ranges. They can run at up to 70 km/h. They mostly inhabit broad-leafed savannas and woodlands and are listed as vulnerable and have a wild population of 12,000-14,000

Greater Kudu

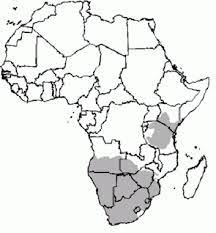

The greater kudu is a large woodland antelope, you can see its distribution on the map. Despite occupying such widespread territory, they are sparsely populated in most areas due to declining habitat, deforestation, and poaching.

The greater kudu is a large woodland antelope, you can see its distribution on the map. Despite occupying such widespread territory, they are sparsely populated in most areas due to declining habitat, deforestation, and poaching.

The spiral horns are impressive, and grow at one curl every 3 years – they are fully grown at 7 and a half years with 2 and a half turns. Three subspecies have been agreed (one described has been rejected) :

- T. s. strepsiceros – southern parts of the range from southern Kenya to Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa

- T. s. chora – northeastern Africa from northern Kenya through Ethiopia to eastern Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea

- T. s. cottoni – Chad and western Sudan

Lesser Kudu

The lesser kudu is a medium-sized bushland antelope found in East Africa. It was first scientifically described by English zoologist Edward Blyth (1869).It stands around 90 cm at the shoulder and weigh from 45 to 80 kg. They are generally solitary, territorial browsers.

lesser kudu is a medium-sized bushland antelope found in East Africa. It was first scientifically described by English zoologist Edward Blyth (1869).It stands around 90 cm at the shoulder and weigh from 45 to 80 kg. They are generally solitary, territorial browsers.

While currently rated not threatened, its population is decreasing. It currently stands at 100,000, but it is loosing territory to humans

Common Bongo (and mountain Bongo)

The bongo is a large, mostly nocturnal, forest-dwelling antelope, native to sub-Saharan Africa. Bongos are characterised by a striking reddish-brown coat, black and white markings, white-yellow stripes, and long slightly spiralled horns. It is the only member of its family in which both sexes have horns. Bongos have a complex social interaction and are found in African dense forest mosaics. They are the third-largest antelope in the world.

The bongo is a large, mostly nocturnal, forest-dwelling antelope, native to sub-Saharan Africa. Bongos are characterised by a striking reddish-brown coat, black and white markings, white-yellow stripes, and long slightly spiralled horns. It is the only member of its family in which both sexes have horns. Bongos have a complex social interaction and are found in African dense forest mosaics. They are the third-largest antelope in the world.

The Common (western or lowland bongo), faces an ongoing population decline, and the IUCN considers it to be Near Threatened.

The mountain bongo (or eastern) of Kenya, has a coat even more vibrant than the common version. The mountain bongo is only found in the wild in a few mountain regions of central Kenya. This bongo is classified by the IUCN as Critically Endangered (where it breeds readily). (this is not on the map above). Only 100 live wild, split between 4 areas of Kenya

Nyala

The Nyala is a spiral horned species

found in Southern Africa. The nyala is mainly active in the early morning and the late afternoon. It generally browses during the day if temperatures are 20–30 °C and during the night in the rainy season. The nyala feeds upon foliage, fruits and grasses, and requires sufficient fresh water. It is a very shy animal, and prefers water holes to the river bank. Not territorial, they are very cautious creatures. They live in single-sex or mixed family groups of up to 10 individuals, but old males live alone. They inhabit thickets within dense and dry savanna woodlands. The main predators of the nyala are lion, leopard and African wild dog, while baboons and raptorial birds prey on juveniles. Males and females are sexually mature at 18 and 11–12 months of age respectively, though they are socially immature until five years old. They have one calf after 7 months of gestation. Its population is stable, with the greatest threat coming from habitat loss as humans expand. There are thought to be 36500 and the population is stable.

Mountain Nyala

The mountain Nyala ( also known as the Balbok) is a large antelope found in high altitude woodlands in just a small part of central Ethiopia. The coat is grey to brown, marked with two to five poorly defined white strips extending from the back to the underside, and a row of six to ten white spots. White markings are present on the face, throat and legs as well. Males have a short dark erect crest, about 10 cm (3.9 in) high, running along the middle of the back. Only males possess horns.

also known as the Balbok) is a large antelope found in high altitude woodlands in just a small part of central Ethiopia. The coat is grey to brown, marked with two to five poorly defined white strips extending from the back to the underside, and a row of six to ten white spots. White markings are present on the face, throat and legs as well. Males have a short dark erect crest, about 10 cm (3.9 in) high, running along the middle of the back. Only males possess horns.

The mountain nyala are shy and elusive towards human beings. They form small temporary herds. Males are not territorial. Primarily a browser. They will grazing occasionally. Males and females are sexually mature at 2 years old.. Gestation lasts for eight to nine months, after which a single calf is born. The lifespan of a mountain nyala is around 15 to 20 years.

Found in mountain woodland -between 3000m and 4000m. Human settlement and large livestock population have forced the animal to occupy heath forests at an altitude of above 3,400 m (11,200 ft). Mountain nyala are endemic to the Ethiopian highlands east of the Rift Valley. As much as half of the population live within 200 square km (77 sq mi) area of Gaysay, in the northern part of the Bale Mountains National Park. The mountain nyala has been classified under the Endangered category of the (IUCN). Their influence on Ethiopian culture is notable, with the mountain nyala being featured on the obverse of Ethiopian ten cents coins.

Situnga Antelope

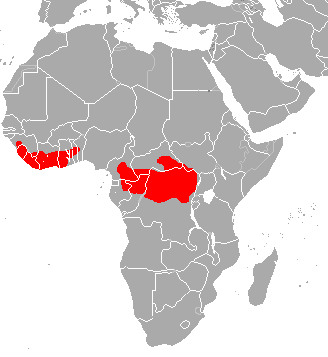

The sitatunga (or marshbuck)is a  swamp-dwelling medium-sized antelope found throughout central Africa (see the map to the right. The sitatunga is mostly confined to swampy and marshy habitats. Here they occur in tall and dense vegetation as well as seasonal swamps, marshy clearings in forests, riparian thickets and mangrove swamps.

swamp-dwelling medium-sized antelope found throughout central Africa (see the map to the right. The sitatunga is mostly confined to swampy and marshy habitats. Here they occur in tall and dense vegetation as well as seasonal swamps, marshy clearings in forests, riparian thickets and mangrove swamps.

The scientific name of the sitatunga is Tragelaphus spekii. The species was first described by the English explorer John Hanning Speke in 1863.

It is listed as least concern with 170,000-200,000, and are found in 25 countries. However 40% live outside reserves, so the situation could get worse fast.

Note: these animals have been dealt with in less detail than others. Should you be interested in finding out if I have written on these animals or what exactly I said, you can find a list of articles about each below its information.

The

The

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species.

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species. common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

Impala

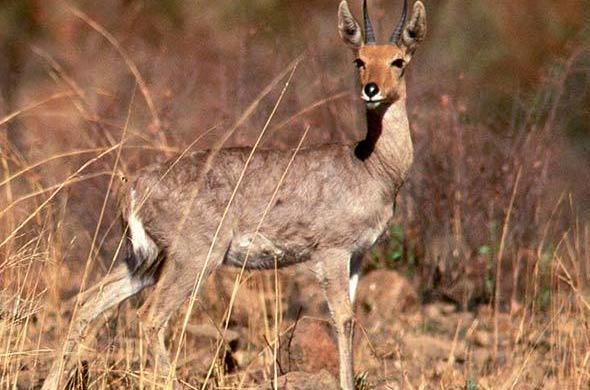

Impala antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

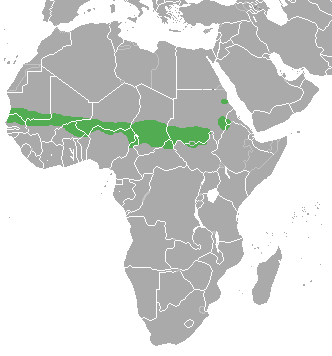

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle.

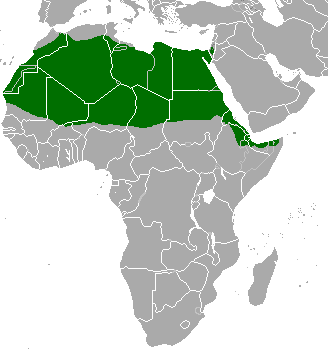

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle. Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places. A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice. The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams.

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams.  The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink. A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda. The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

Reedbuck is found in Southern Africa. It is a midsized

Reedbuck is found in Southern Africa. It is a midsized

The Nile lechwe or Mrs Gray’s lechwe is an endangered species of antelope found in swamps and grasslands in South Sudan and Ethiopia.

The Nile lechwe or Mrs Gray’s lechwe is an endangered species of antelope found in swamps and grasslands in South Sudan and Ethiopia.

The puku is a medium-sized antelope found in wet grasslands in southern Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and more concentrated in the Okavango Delta in Botswana. Nearly one-third of all puku are found in protected areas, zoos, and national parks due to their diminishing habitat (the issue here, is that these 2/3 are clearly at danger of disappearing if humans change their behaviour. They are currenly listed as not threatened

The puku is a medium-sized antelope found in wet grasslands in southern Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and more concentrated in the Okavango Delta in Botswana. Nearly one-third of all puku are found in protected areas, zoos, and national parks due to their diminishing habitat (the issue here, is that these 2/3 are clearly at danger of disappearing if humans change their behaviour. They are currenly listed as not threatened

Image source

Image source

The Iberian wolf is a subspecies of the grey wolf found on the Iberian peninsular. It reached its minimum in the 1970s with 500-700 iindividuals living in the wild. Until the middle of the 19th century, it was widespread, throughout the Iberian peninsular. It should be noted, that wolves have never had high densities, and the wolves of western Europe are not thought to have ever had a population much above 848–26 774 (depending on which end of the estimate you rely – but is the founding population of both the Iberian and Apennine population).

The Iberian wolf is a subspecies of the grey wolf found on the Iberian peninsular. It reached its minimum in the 1970s with 500-700 iindividuals living in the wild. Until the middle of the 19th century, it was widespread, throughout the Iberian peninsular. It should be noted, that wolves have never had high densities, and the wolves of western Europe are not thought to have ever had a population much above 848–26 774 (depending on which end of the estimate you rely – but is the founding population of both the Iberian and Apennine population).

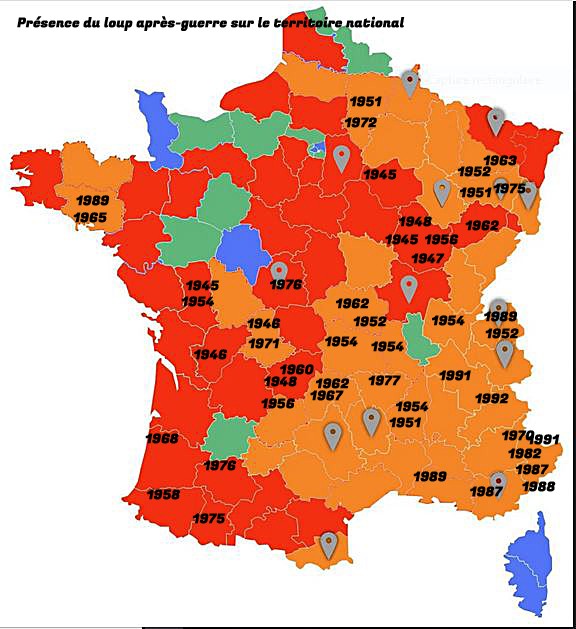

The Apennine wolf is also known as the Italian wolf. Back in the 1970s the population reached its minimum, where the population reached 70-100 individuals. It has recovered well since then, with an Italian population of roughly 3300. However, since the early 1990s, this subspecies has been gradually moving into France. As such, at the end of 2022 the number was estimated at 1104 wolves in France.

The Apennine wolf is also known as the Italian wolf. Back in the 1970s the population reached its minimum, where the population reached 70-100 individuals. It has recovered well since then, with an Italian population of roughly 3300. However, since the early 1990s, this subspecies has been gradually moving into France. As such, at the end of 2022 the number was estimated at 1104 wolves in France.

The Eurasian wolf (often referred to as the Russian wolf), is the subspecies which runs down the east coast of the Adriatic sea, as well as the majority of Russia and northern Europe.

The Eurasian wolf (often referred to as the Russian wolf), is the subspecies which runs down the east coast of the Adriatic sea, as well as the majority of Russia and northern Europe.

The Tundra wolf – Canis lupus Albus is the Eurasian equivalent of the Arctic wolf. Also known as the Turukhan wolf, it is native to Eurasia’s tundra and forest-tundra zones from Finland to the Kamchatka Peninsula. It was first described in 1792 by Robert Kerr.

The Tundra wolf – Canis lupus Albus is the Eurasian equivalent of the Arctic wolf. Also known as the Turukhan wolf, it is native to Eurasia’s tundra and forest-tundra zones from Finland to the Kamchatka Peninsula. It was first described in 1792 by Robert Kerr.

The Indian wolf is one of the more well known, partly as their starring role in the Jungle book by Rudyard Kipling. I do remember my great grandmother talking about seeing 4 wolves running in the distance. It is thought to have 2000-3000 individuals left in the wild, though given its former large range, this does not appear very high. It should not be surprising, therefore, to hear that this is considered as one of the most endangered subspecies of the grey wolf – it officially has the conservation status of endangered – now it is considered endangered, and people talk about it at high risk, but it should be remembered that there are still 2000-3000, which is a pretty high number for a species considered more than just endangered.

The Indian wolf is one of the more well known, partly as their starring role in the Jungle book by Rudyard Kipling. I do remember my great grandmother talking about seeing 4 wolves running in the distance. It is thought to have 2000-3000 individuals left in the wild, though given its former large range, this does not appear very high. It should not be surprising, therefore, to hear that this is considered as one of the most endangered subspecies of the grey wolf – it officially has the conservation status of endangered – now it is considered endangered, and people talk about it at high risk, but it should be remembered that there are still 2000-3000, which is a pretty high number for a species considered more than just endangered.

The Steppe wolf also known as the Caspian sea wolf is a wolf subspecies that is found in the region around the Caspian sea, though the Steppe wolf is perhaps more useful a name as it extends far from the Caspian sea. Much of its range is in Kazakhstan as the working figure is 30,000 individuals, however, the survey which produced this number was completed in 2007, and given the lack of any protection and the widespread enjoyment, got from hunting wolves, it seems highly unlikely that the current population is anywhere near that size.

The Steppe wolf also known as the Caspian sea wolf is a wolf subspecies that is found in the region around the Caspian sea, though the Steppe wolf is perhaps more useful a name as it extends far from the Caspian sea. Much of its range is in Kazakhstan as the working figure is 30,000 individuals, however, the survey which produced this number was completed in 2007, and given the lack of any protection and the widespread enjoyment, got from hunting wolves, it seems highly unlikely that the current population is anywhere near that size.

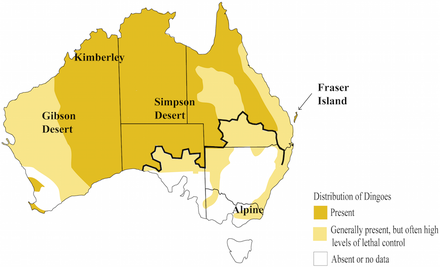

Closely related to the new Guinea singing dog, the Dingo is a dog species that has a relatively wide range. There is some debate about how it got to some of its homes, and whether it may have come alongside early humans.

Closely related to the new Guinea singing dog, the Dingo is a dog species that has a relatively wide range. There is some debate about how it got to some of its homes, and whether it may have come alongside early humans.

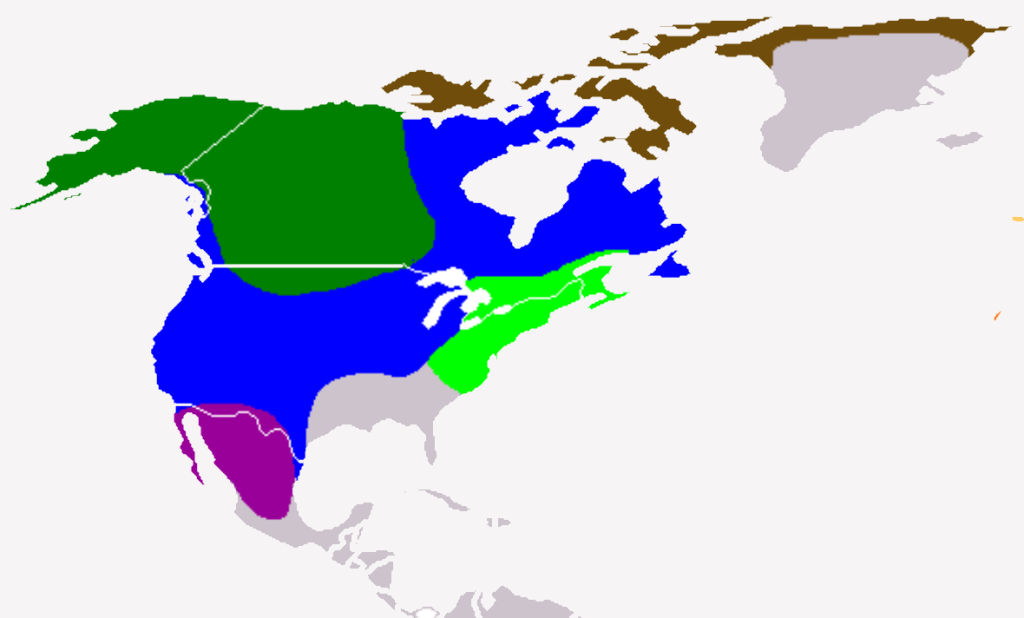

Mexican wolves (scientific name is Canis lupus baileyi) are currently only found in a small area as seen on the map to the right. It is a fantastic improvement on the situation around 1970 when the species was extinct in the wild. The first reintroduction was carried out in 1998. Unfortunately, founded by just 7 individuals, the population is highly inbred. Never-the-less, currently, the

Mexican wolves (scientific name is Canis lupus baileyi) are currently only found in a small area as seen on the map to the right. It is a fantastic improvement on the situation around 1970 when the species was extinct in the wild. The first reintroduction was carried out in 1998. Unfortunately, founded by just 7 individuals, the population is highly inbred. Never-the-less, currently, the

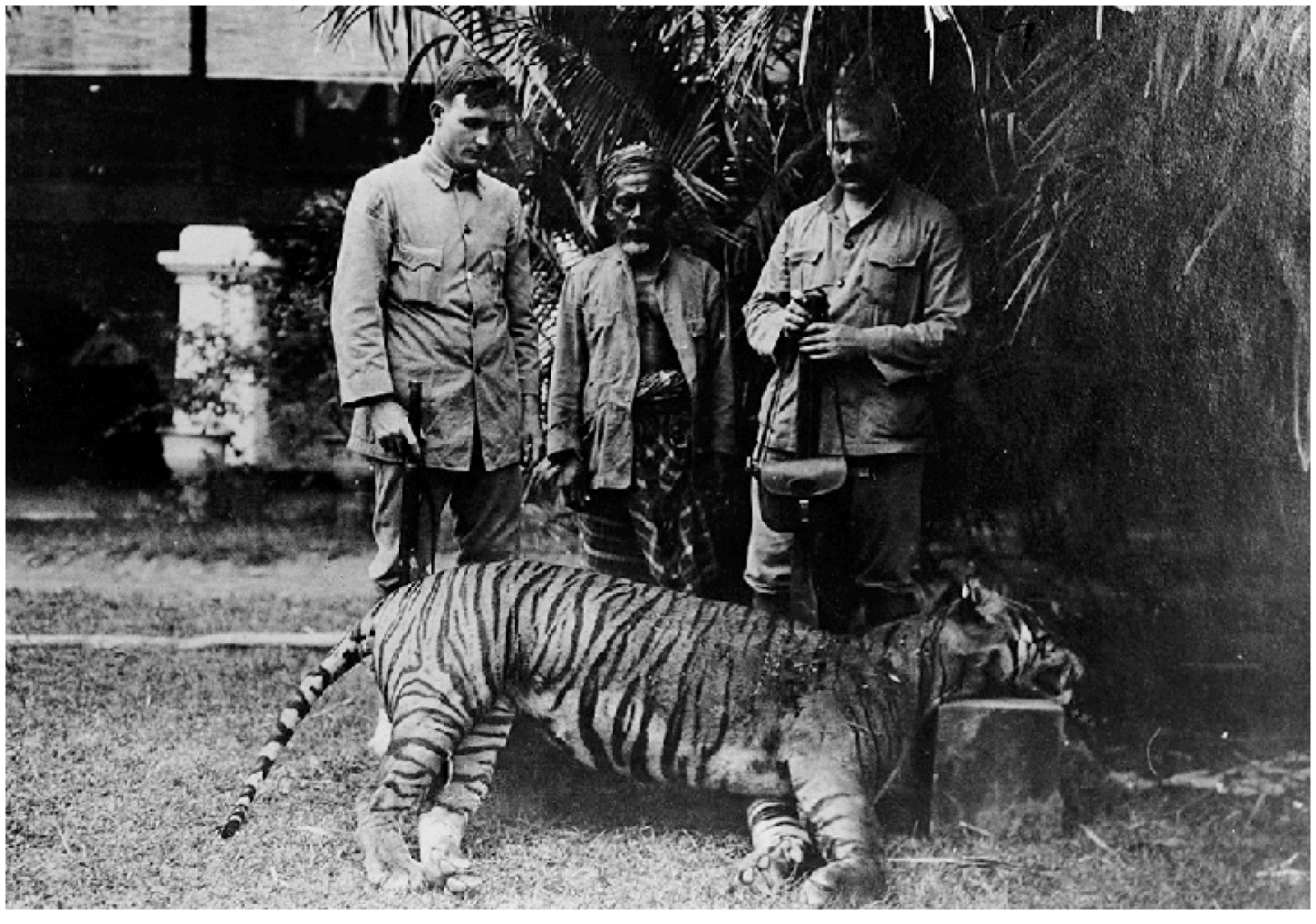

The country with the most tigers is India, hosting around 70% of the remaining tigers, or a little over 3000. However, this is down from 100,000 in 1900. In 2006 the Indian tiger population was as low as just 1411 – there are individual reserves in Africa with more lions in than this number. Given that there are 54 tiger reserves in India, that leaves an average population of just 30 per reserve – translocation will be required to maintain genetically healthy tigers. Formerly working on pug-marks, counting has been replaced with photo identification, as pug marks were overestimating the population (Simlipal reserve in Orissa state claimed 101 tigers in 2004, yet in 2010 a photo count stated 61, and this is thought a a huge over estimate, as the same state government claims just 45 tigers across the state. Sariska and Panna reserves in India are worse with the government having to admit that there are no tigers left (2 reserves of at least 5 so called tiger reserves with none left).

The country with the most tigers is India, hosting around 70% of the remaining tigers, or a little over 3000. However, this is down from 100,000 in 1900. In 2006 the Indian tiger population was as low as just 1411 – there are individual reserves in Africa with more lions in than this number. Given that there are 54 tiger reserves in India, that leaves an average population of just 30 per reserve – translocation will be required to maintain genetically healthy tigers. Formerly working on pug-marks, counting has been replaced with photo identification, as pug marks were overestimating the population (Simlipal reserve in Orissa state claimed 101 tigers in 2004, yet in 2010 a photo count stated 61, and this is thought a a huge over estimate, as the same state government claims just 45 tigers across the state. Sariska and Panna reserves in India are worse with the government having to admit that there are no tigers left (2 reserves of at least 5 so called tiger reserves with none left).

Russia hosts one of the hardest tigers to see. However, there are now around 500 Amur tigers roaming the remote far east of Russia, up from less than 40 in the 1940s, this population has also had great gains.

Russia hosts one of the hardest tigers to see. However, there are now around 500 Amur tigers roaming the remote far east of Russia, up from less than 40 in the 1940s, this population has also had great gains.