Dugong and Manatees

The family Sirenia consists of 2 genus, the Dugongidae (only extant species is the Dugong) and Trichechidae which contains the 3 Manatee species.

The Dugong is the species in the top left (if you cannot pick it out). The Steller sea cow was a close relation of the Dugong

The big difference, is that unlike Manatees with a paddle shaped tail, where as Dugongs have fluked tails.

As always, as links are made to help with tourism, these will either appear below, or each species will be spun off to have its own page. Ecotourism need not have a big impact on the species and its natural behaviour, however, by giving them financial value to the local population you greatly increase the liklihood of survival as well as increasing the standard of living for local people.

Should you work in tourism dealing with these species, do get in touch, there is a link at the top of the home page, with a simple form.

Dugong– The only surviving Dugongidae after the stellers sea cow (described in 1741 and hunted to extinction by 1768 for hide meat and fat) was lost.

Dugong– The only surviving Dugongidae after the stellers sea cow (described in 1741 and hunted to extinction by 1768 for hide meat and fat) was lost.

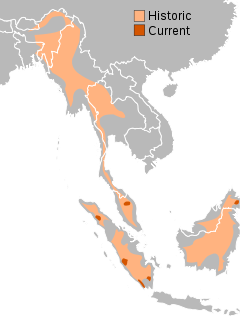

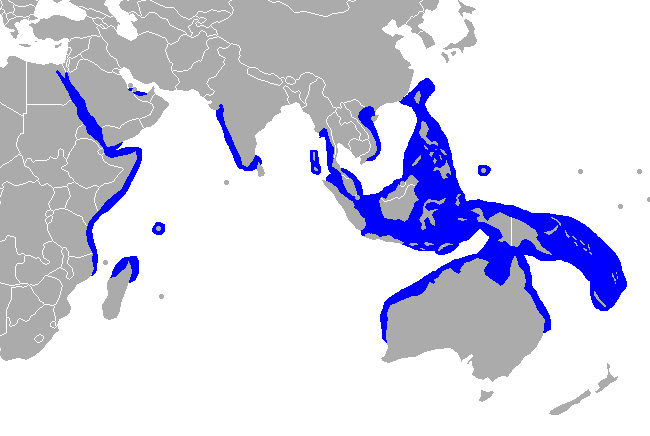

It is found in the waters of around 37 countries in the Indo-west Pacific. It has recently become functionally extinct in Chinese waters, and may well be lost entirely in the near future. Its thought that while their current range is highly fractured, it is probably still a similar limit to before. These countries between them, give around 140,000km of coastline, and this area maps with where the correct species of sea grasses grow. The worldwide population is thought to have declined 20% in the last 90 years, though this is pretty good compared to many other species.

There are currently thought to be 100,000, with its conservation status being Vulnerable

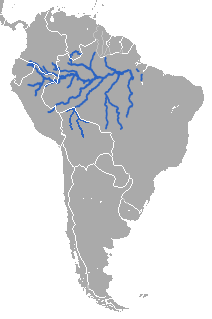

Amazon ian Manatee-Found in parts of the Amazon basin, throughout parts of Brazil, Colombia Peru and Ecuador.

ian Manatee-Found in parts of the Amazon basin, throughout parts of Brazil, Colombia Peru and Ecuador.

It is the smallest of the surviving Manatees. Weights fall between 7,5kg and 350kg, with a 75cm-225cm length. Given that it is likely decreasing, it is going to be below this now.

They are exclusively herbivorous, feeding on water lettuce and hyacinth. During a day, they can consume around 8% of their bodyweight. This mostly occurs during the wet season, during the dry season they return to the main river and survive on their fat reserves. They have a prehensile snout (like a less developed trunk) for feeding

They are considered Vulnerable, with the last count giving an upper limit of 10,000, however, this was in 1997.

West-Indian manatee- So na med, because they were first sighted amongst a group of Islands called the West-Indies in the Caribbean – it is no-where near India (as you can see). They live in shallow coastal areas. They have a prehensile snout (like a less developed trunk) for feeding. Unlike elephants, they are not limited to 6 sets of teeth, but only having molars (24-36) it is a simpler layout. As their range includes Florida (well known from the Everglades) this species is well known in places. They are hard to count, living in murky water,

med, because they were first sighted amongst a group of Islands called the West-Indies in the Caribbean – it is no-where near India (as you can see). They live in shallow coastal areas. They have a prehensile snout (like a less developed trunk) for feeding. Unlike elephants, they are not limited to 6 sets of teeth, but only having molars (24-36) it is a simpler layout. As their range includes Florida (well known from the Everglades) this species is well known in places. They are hard to count, living in murky water,

Listed as vulnerable, the whole population is not thought to be greater than 10,000. The 2 subspecies are the Florida manatee (around 2500) and the Antillean Manatee which is found off the Atlantic coast of Mexico and central south America (particularly in the waters of greater Antilles) potentially, historically found along the coast of Texas (and as far north as Dennis, Tennessee).

African Manatee- (or West African Manatee) Although found both on the coast and inland, there is no significant genetic difference between these populations. African Manatees can be found in West African regions which include a wide range of countries – requiring cross nation action to save them. Manatees are found in brackish waters to freshwater: in oceans, rivers, lakes, coastal estuaries, reservoirs, lagoons, and bays on the coast.

Manatee) Although found both on the coast and inland, there is no significant genetic difference between these populations. African Manatees can be found in West African regions which include a wide range of countries – requiring cross nation action to save them. Manatees are found in brackish waters to freshwater: in oceans, rivers, lakes, coastal estuaries, reservoirs, lagoons, and bays on the coast.

The areas with the highest manatee populations are Guinea-Bissau, the lagoons of Côte d’Ivoire, the southern portions of the Niger River in Nigeria, the Sanaga River in Cameroon, the coastal lagoons in Gabon, and the lower parts of the Congo River. Alone amongst manatee species, the African manatee is Omnivorous, eating clams and molluscs as well as fish found in nets (can make up 50% of diet). They are more adaptable than other manatees, being able to survive in salt water (though they need access to fresh water to drink).

They are nocturnal, but many countries, a dead manatee is worth a lot to hunters. They are listed on CITES Appendix 1 with a population under 10,000. Cote d’Ivoire has a population of 750-800. Some of the biggest populations still live in Gabon, status is unknown in many areas. There is much tourism potential – worth a lot in Florida.