It is back in the 1940s that wolves were last resident in the Grand Canyon national park. This is why it was so exciting that a grey wolf is roaming the northern rim of the grand canyon.

Wildlife and conservation new, wild travel information and links for booking

It is back in the 1940s that wolves were last resident in the Grand Canyon national park. This is why it was so exciting that a grey wolf is roaming the northern rim of the grand canyon.

There are currently no know Mexican wolves in Mexico, with the last 5 having been captured in 1980 to create a breeding program. It is possible that a few survived and have not been seen (there is a great deal of wilderness in Mexico), but from what is known they are none left in Mexico.

The wolf is a species that is often on the top of the list of animals that people would like to see in the wild before they die. It is truly a wonderful thing to see.

I have been lucky enough to see them twice, once from a bear hide in Sweden (look at the hide list, this one is the only currently available) as well as also seeing an Iberian wolf briefly, as well as hearing them in the distance.

There is something magical about being in an ecosystem where you are not the only dangerous animal. Wolves are not dangerous in the same way as the big 5 from Africa. Even spending years in the field, you are unlikely to actually to get close to a wolf, and if you do, more often than anything it will run. For much of Europe, humans are having to get used to living alongside them, having destroyed the population in the last few hundred years. But they are essential for a balanced ecosystem – i certainly hope that eventually they will return to this country.

As many as 38 subspecies are listed, and as we make contacts for people to see the wolves, we will add more subspecies. Some examples include the Eurasian wolf, the Indian wolf, the Iberian wolf and even the domestic dog. However, it was found that many of these interbred along their boundary suggesting they are more of a clade than a subspecies. As such, below i have split the wolf species into 2 groups, old and new world wolves. Each will have a page, thought these will remain relatively sparse until we start adding links for where you can see them. I should add (once again) that this is a page for subspecies of the grey wolf. Any closely related wolf like the Alonquin wolf (eastern wolf) or the red wolf have pages of their own, as they have been granted separate species status (as opposed to separate subspecies, which will be listed on this page)

There is a great thirst in our increasingly artificial lives, for people to experience the wild. It is true that many do this on safari in Africa, or on a whale watching trip, but the interest in seeing wolves in their native environment only grows as time goes by.

The wolf is an apex predator. By hunting in packs, they are able to take down much larger prey than they would be alone, though a number of different subspecies have given up this advantage to be able to survive in places where large prey is not available. Subspecies like the African wolf subsist on rats and birds and rabbits and species of similar size. They are incredibly intelligent (when trekking in the Romania mountains we saw the sign of recent visits by the wolves, in order to plan their attack on the vast sheep flocks which would be herded through this narrow valley, several months later) and can plan a significant distance into the future. The Ethiopian wolf (a species that is not a subspecies of the grey wolf, but closely related) hunts in a very similar way, but not being a subspecies of the grey wolf will not appear on this page (it has its own page, accessible from the wild dog page or click here). The domestic dog is a subspecies. The African wild dog, is a relation of the wolf, but is not a subspecies. It is thought that it last shared an ancestor with the wolf around 2 million years ago.

Below is an image of a range of old world wolf subspecies. Each one will have a page devoted to it, and over time, we hope to list places to see each one in the wild. We rely on people who live alongside these animals to list places that people can see them (the whole purpose of this website is to create a wildlife travel marketplace, if you live somewhere wild, list it and make money while showing the world the amazing wildlife on your doorstep (if it is not a wolf, find your species – we wish long term to cater for all)

Old world grey wolf subspecies – Europe Asia Africa (note- the name of each has wolf after it – Iberian wolf etc. This does not apply to the last two). Below is a map of the rough range of the old world species

The Iberian wolf is a subspecies of the grey wolf found on the Iberian peninsular. It reached its minimum in the 1970s with 500-700 iindividuals living in the wild. Until the middle of the 19th century, it was widespread, throughout the Iberian peninsular. It should be noted, that wolves have never had high densities, and the wolves of western Europe are not thought to have ever had a population much above 848–26 774 (depending on which end of the estimate you rely – but is the founding population of both the Iberian and Apennine population).

The Iberian wolf is a subspecies of the grey wolf found on the Iberian peninsular. It reached its minimum in the 1970s with 500-700 iindividuals living in the wild. Until the middle of the 19th century, it was widespread, throughout the Iberian peninsular. It should be noted, that wolves have never had high densities, and the wolves of western Europe are not thought to have ever had a population much above 848–26 774 (depending on which end of the estimate you rely – but is the founding population of both the Iberian and Apennine population).

They have been gradually spreading from their 1970s holdout – in a hunting reserve called the Sierra de Culebra which is a hunting reserve straddling the North eastern border of Portugal, and across the border in Spain. This reserve is fascinating, and may well be a good way to support wolves in other areas. There is significant belief that the wolf populations in Southern Spain is extinct, however, should the recovery of the Iberian wolf is allowed to continue, I could well see wolves re-settling these areas within the next couple of decades

They have in recent years, started to meet with Apennine wolves, who re-entered France back in 1991-1992, and settled in the Pyrenees. The small pockets of wolves in Southern Spain are isolated and are certainly threatened long-term. The Iberian wolf had its last survey in 2021, and at that time the number of wolves was estimated at 2000-2500. It should be noted that in 2021 wolf hunting was banned in Spain – between 2008 and 2013, 623 Iberian wolves were hunted legally, and I think that it is fantastic that this has been banned. Having said that, it means that the wolf hunting number was around 5% of the wolves in the country each year. This is at a level which should allow the population to grow over time.

These wolves are fascinating to see in the wild (I have seen them and heard them), and the best way to make sure that they say in the wild is to go see them. They are fantastic for ecosystems, and are very exciting to see in the wild. As we add destinations, they will appear below.

The Apennine wolf is also known as the Italian wolf. Back in the 1970s the population reached its minimum, where the population reached 70-100 individuals. It has recovered well since then, with an Italian population of roughly 3300. However, since the early 1990s, this subspecies has been gradually moving into France. As such, at the end of 2022 the number was estimated at 1104 wolves in France.

The Apennine wolf is also known as the Italian wolf. Back in the 1970s the population reached its minimum, where the population reached 70-100 individuals. It has recovered well since then, with an Italian population of roughly 3300. However, since the early 1990s, this subspecies has been gradually moving into France. As such, at the end of 2022 the number was estimated at 1104 wolves in France.

The Italian wolf is considered the national animal of the country (at least by some) and features heavily in writings from across the history of the country (going back as far as the Roman empire). It was listed as a subspecies back in 1921, and the range almost exactly 100 years ago in 2019 is shown to the right. It should be noted, that wolf range is likely to have increased significantly in the 5 years that have run since this map was created.

The genetics of this subspecies suggests that it went through a genetic bottleneck in the last 20,000 or so year, and it is thought wolves were isolated south of the alps, and unable to exchange DNA with any other group of wolves. Now they have been able to move beyond the alps, this isolation appears to be over, and there are already couples breeding, which will improve the health of each population as a whole. Keep an eye on the news box below which will list articles on this subspecies.

The Apennine wolf is found throughout much of Italy, and an increasingly large parts of France, as well as even sections in Spain in the Pyrenees. There is much wilderness across its range, and as such there is likely space for a far larger population. It is also worth noting, that the deer population across Italy and France is higher than it has been for some time, and as such a recovered wolf population is likely to control these at more natural levels.

Never-the-less, there is much tourism in all of the range of the Apennine wolf. Any places that we have listed to see this wolf subspecies will appear below.

The Eurasian wolf (often referred to as the Russian wolf), is the subspecies which runs down the east coast of the Adriatic sea, as well as the majority of Russia and northern Europe.

The Eurasian wolf (often referred to as the Russian wolf), is the subspecies which runs down the east coast of the Adriatic sea, as well as the majority of Russia and northern Europe.

It ranges through Scandinavia, the Caucasus, Russia, China, and Mongolia. Its habitat overlaps with the Indian wolf in some regions of Türkiye.

In South eastern Europe it is found in much of the countries in which it lives, but not throughout the area (its distribution is patchy, but relatively easy to move between areas where they are found). The numbers are thought to be roughly 3900 throughout this area.

Its Scandinavian population is not large, but it is thought to still be connected with its Russian population so there is no worry about genetic bottlenecks. Norway and Sweden are thought to have a population of around 450 in total. Around 80% of these are in Sweden, though this is by choice- despite the large area of Norway, they state than 95% of the country should remain wolf free, and the remaining area can only support 3 breeding pairs. This is not scientific but political and as such takes intensive culling each year. Finland has a current population of 300 which is the highest for a century, though modelling suggests a population under 500 is unlikely to remain healthy for long; though given the proximity of Finland to Russia, wolves are able to regularly interbreed across the border.

The Russian wolf population is the largest, and accounts for most of Russia’s wolves. The population was estimated at 40,000. They are hunted, but at the current time, their population appears to be pretty stable.

The Chinese population is 10,000-12,000, while Mongolia has 10,000-20,000

Although, the only subspecies to take the name Russian, Russia hosts a range of wolf subspecies. Also known as the Northern Asian subspecies. I have not found much information on this subspecies, but hope to add more soon as it becomes available.

In places like reserves, these wolves are seen relatively regularly. The reserve we visited a bear hide, has a permanent person looking after it, and he claimed he saw wolves about once a week. While this sub-species does not have a population growing particlarly fast, it is also not shrinking fast either.

We will aim to list places to see them below. Do get in touch if you have somewhere that you do see these wolves regularly, and would like to list your destination. Letting other people pay to see the wildlife that you see all the time, can help reward their ongoing survival as well as bringing in some money which can help you .

The Tundra wolf – Canis lupus Albus is the Eurasian equivalent of the Arctic wolf. Also known as the Turukhan wolf, it is native to Eurasia’s tundra and forest-tundra zones from Finland to the Kamchatka Peninsula. It was first described in 1792 by Robert Kerr.

The Tundra wolf – Canis lupus Albus is the Eurasian equivalent of the Arctic wolf. Also known as the Turukhan wolf, it is native to Eurasia’s tundra and forest-tundra zones from Finland to the Kamchatka Peninsula. It was first described in 1792 by Robert Kerr.

The tundra wolf generally rests in river valleys, thickets and forest clearings. In winter it generally feeds on female or young wild and domestic reindeer, though smaller animals like hares, arctic foxes and other animals are sometimes taken. A survey of stomach contents of 74 wolves caught around Nenets Autonomous Okrug in the 1950s were found to consist of 93.1% reindeer remains. In the summer period, tundra wolves feed extensively on birds and small rodents, as well as newborn reindeer calves.

They are classed as least concern, and as can be seen, have a large range. There is no estimate of their numbers, but it is likely to be one of the more numerous in the world. (if anyone has further information do let me know). As yet, I have not written about the Tundra wolf – it is not easy to find information on it. However, as blogposts are written on this subspecies, they will appear below. It should be noted that when you look up Arctic or Tundra wolf, a number of webpages quote figures of 200,000

The Indian wolf is one of the more well known, partly as their starring role in the Jungle book by Rudyard Kipling. I do remember my great grandmother talking about seeing 4 wolves running in the distance. It is thought to have 2000-3000 individuals left in the wild, though given its former large range, this does not appear very high. It should not be surprising, therefore, to hear that this is considered as one of the most endangered subspecies of the grey wolf – it officially has the conservation status of endangered – now it is considered endangered, and people talk about it at high risk, but it should be remembered that there are still 2000-3000, which is a pretty high number for a species considered more than just endangered.

The Indian wolf is one of the more well known, partly as their starring role in the Jungle book by Rudyard Kipling. I do remember my great grandmother talking about seeing 4 wolves running in the distance. It is thought to have 2000-3000 individuals left in the wild, though given its former large range, this does not appear very high. It should not be surprising, therefore, to hear that this is considered as one of the most endangered subspecies of the grey wolf – it officially has the conservation status of endangered – now it is considered endangered, and people talk about it at high risk, but it should be remembered that there are still 2000-3000, which is a pretty high number for a species considered more than just endangered.

It is found in arid and semi-arid peninsular plains of India, though from the distribution map to the right, you can see that much of its range is found outside India. The Indian wolf lives in smaller packs of 6-8. It has a reputation for cunning, and makes far less noises than other wolves, having very rarely been known to howl. As you can see from the map to the right, although called the Indian wolf, its range stretches far beyond the borders of India

It was described in 1831.

Also the most recently confirm subspecies of the wolf – the African wolf. The move onto the African continent has required a number of changes in behaviour, which makes it easily confused with Jackels, but the African wolf is indeed a wolf. It split from the wolf/coyote ancestor just over a million years ago. Previously, it was considered a subspecies of the Golden Jackal.

There are two genetically distinct populations, one in North-West Africa and the other in East Africa. It appears to be roughly 72% genetically grey wolf, with the rest coming from the Ethiopian wolf (while the Ethiopian wolf is considered a separate species, it is a closely related Canid).

It was only reidentified (having been originally identified in 1820) in 2015, so there is still much to be done, both in identifying size of population and variations of he population across Africa. Given the huge area that they are found in, it seems quite reasonable that there will be further splitting of the African wolf into separate subspecies (or merely populations, though given the huge distances between them we will have to wait and see) but we will find this out in time.

There has been little study of this species, and it is unclear exactly how much range that it has. Hopefully, this will happen in time, but it is clear that the big problem is telling the difference between golden jackals and golden wolves.

African wolf range

There are a number of subspecies of the African wolf (quite quick, given it was not redeclared as a species 6 years ago. They are classed as a least concern. While not all sub-species have a clear estimate of the current population, genetic analysis suggests that the historic population was not smaller than 80,000 females.

The Steppe wolf also known as the Caspian sea wolf is a wolf subspecies that is found in the region around the Caspian sea, though the Steppe wolf is perhaps more useful a name as it extends far from the Caspian sea. Much of its range is in Kazakhstan as the working figure is 30,000 individuals, however, the survey which produced this number was completed in 2007, and given the lack of any protection and the widespread enjoyment, got from hunting wolves, it seems highly unlikely that the current population is anywhere near that size.

The Steppe wolf also known as the Caspian sea wolf is a wolf subspecies that is found in the region around the Caspian sea, though the Steppe wolf is perhaps more useful a name as it extends far from the Caspian sea. Much of its range is in Kazakhstan as the working figure is 30,000 individuals, however, the survey which produced this number was completed in 2007, and given the lack of any protection and the widespread enjoyment, got from hunting wolves, it seems highly unlikely that the current population is anywhere near that size.

As you can see from the map, its range is largely split between Kazakhstan and and teh western end of russia.

The Arabian wolf is found sporadically around the edge of the Arabian peninsular, with a total population of 1000-3000. The Arabian wolf was once found throughout the Arabian Peninsula, but now lives only in small pockets in

There is wolf tourism in a variety of places across the middle east, but merely expressing interest in them could well show locals their potential value.

Should you live in an Arabian wolf range area and would like to be able to show visitors these fascinating animals (and get paid for the privilege, do get in touch, we are eager to work with people on the ground. Below is a list of any articles from the website that mention this species, below that is a video of this species in the wild.

The Himalayan wolf (scientifically known as Canis lupus chanco) is a member of the dog family, whose position is debated. Its genes show it is genetically basal to the Holarctic grey wolf, genetically the same wolf as the Tibetan and Mongolian wolf, and has an association with the African wolf (Canis lupaster). No striking morphological differences are seen between the wolves from the Himalayas and those from Tibet. The Himalayan wolf lineage can be found living in Ladakh in the Himalayas, the Tibetan Plateau, and the mountains of Central Asia predominantly above 4,000m in elevation because it has adapted to a low-oxygen environment, compared with other wolves that are found only at lower elevations.

Some experts have suggested that this subspecies is so different to other wolves, that it should be listed as a separate species. In 2019, a workshop hosted by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group noted that the Himalayan wolf’s distribution included the Himalayan range and the Tibetan Plateau. The group recommends that this wolf lineage be known as the “Himalayan wolf” and be classified as Canis lupus chanco until a genetic analysis of the holotypes is available. The Himalayan wolf lacks a proper morphological analysis. The wolves in India and Nepal are listed on CITES Appendix I as endangered due to international trade.

The Himalayan wolf is found in the Himalayan region encompassing India, Nepal and the Tibetan Plateau of Western China. The IUCN report noted that only 2,275 to 3,792 individuals of the Himalayan wolf (Canis lupus chanco) are left in the wild.

The Mongolian wolf (Canis lupus chanco) is not restricted to just Mongolia, but is found in a range of countries in the area as well (see the map to the right for more information). For reference, the blue is the Mongolian wolf range, while the pink is the Himalayan wolf range.

Generally, there is little fear of the Mongolian wolf, and while they do occasionally take livestock they are not persecuted. There is a harvesting of wolf pelts but this is currently done at a sustainable level.

They are considered endangered; they are classed as endangered, with a Mongolian population of 10,000-20,000. I have been unable to identify an overall number for the population.

The new guinea singing dog (also known as the New Guinea highland dog, it is restricted to the highlands of New Guinea. There are a number of different possible names, and places where it fits into the dog family as its taxonomic status is debated, with proposals that include treating it within the species concept (range of variation) of the domestic dog Canis familiaris, a distinct species Canis hallstromi, and Canis lupus dingo when considered a subspecies of the wolf.

Rare amongst canines, it is incapable of barking, instead making an odd yodelling sound, which gives rise to its name.

Genetic analysis suggests that this subspecies is descended from multiple different wolf subspecies. However, it is still debated, though an IUCN workshop in 2019 came to the conclusion that both the singing dogs and the dingo to be populations of the domestic dog, and therefore not needing of protection, or needing to be listed on the IUCN red list.

Oddly, this species was thought to have gone extinct in the wild in 1970 and it was only in 2020 that several wild dogs were genetically tested and found to be this species. Still surviving in captivity, it was a big shock to find them living at heights of over 4km high.

The IUCN will not list them, as it considers them a domestic dog breed, but if this is the case, they are still of interest as they appear frozen in time – a so called “proto domestic dog”. There are around 100 animals in zoos and as domestic exotic pets, but these all originate from around 8 wild members, which means that there is little genetic diversity – leading to possible infertility.

In 2012, a tourist took a photo of an animal which looked suspiciously like the singing dog – taken in a remote mountainous area of New Guinea. When the photo found its way to a certain person, who had been running a program to find it since 1996. McIntyre, the leader of this project, launched a trip to the area and set up many camera traps. Oddly, while some tracks were found, no animals were seen until the last day when a whole pack walked in front of one of the camera traps. While they looked exactly as required, recognizing it would take more than photos to resurrect the singing dog from the dead, he mounted a second trip to the area and set out traps – he caught 2 males, and after taking blood and attaching tracking collars he released them.

After testing against captive singing dogs, it was found to have come from a fully diverse group of wild singing dogs. Some other researchers did suggest that no-one believed these animals to be dead (having found scat on a trip) but there we are.

Might this species be alive and thriving in remote parts of New Guinea? I will hope to write on it in the future – do get in touch if you have information on this fascinating species.

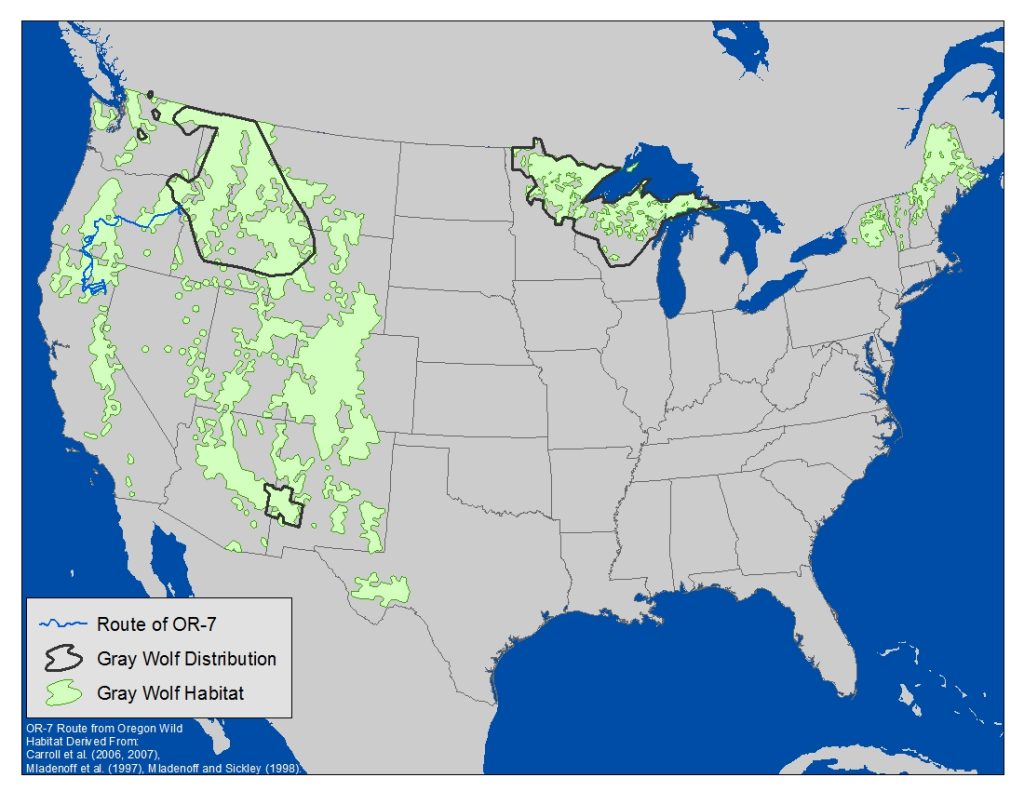

Closely related to the new Guinea singing dog, the Dingo is a dog species that has a relatively wide range. There is some debate about how it got to some of its homes, and whether it may have come alongside early humans.

Closely related to the new Guinea singing dog, the Dingo is a dog species that has a relatively wide range. There is some debate about how it got to some of its homes, and whether it may have come alongside early humans.

The earliest remains of Dingoes in Australia are dated to almost 3500 years ago, While they are now quite happy living alone or alongside humans, it seems that this may be the descendant of early domestic dogs. Interestingly, both genetically and in body shape, these dogs do not appear to have changed much in the 3450 years that they are known to have been in Australia, suggesting a high level of self determination in choice of mate, as opposed to what might have happened with human lead selective breeding. It should be noted that it is thought it arrived far earlier than these earliest remains, with studies suggsting that a sensible arrival date was around 8300 years ago

Given that they have now been on the continent for likely well over 3000 years, it is quite likely that they have done whatever damage that their arrival might cause, and so they are to all intents and purposes a native Australian species.

There is not a particularly strong estimate in the number of Dingoes currently living wild, but it is thought to be between 10,000 and 50,000. Recent genetic studies have shown that over half of the dingoes are pure dingo, with no dog ancestry – putting paid to some attempts to suggest that they are little more than feral dogs, which would make their culling far easier to agree to.

Fraser island, off the coast of Queensland is one of the best places to see the dingo, though there are plenty of other places to head. We hope to add many in the near future, do help us get there.

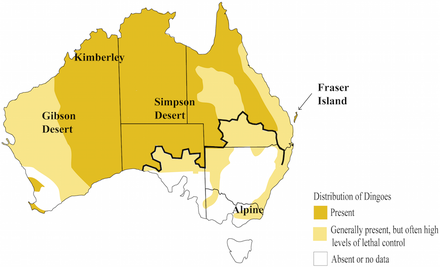

New world wolf subspecies- until recently, as many as 38 wolf subspecies were recognized in North America. The current agreement is that there is just 4-6 (it should be noted that while it has been a debate for over a century, the current agreement is that the red wolf is a separate species and not a subspecies of the grey wolf).

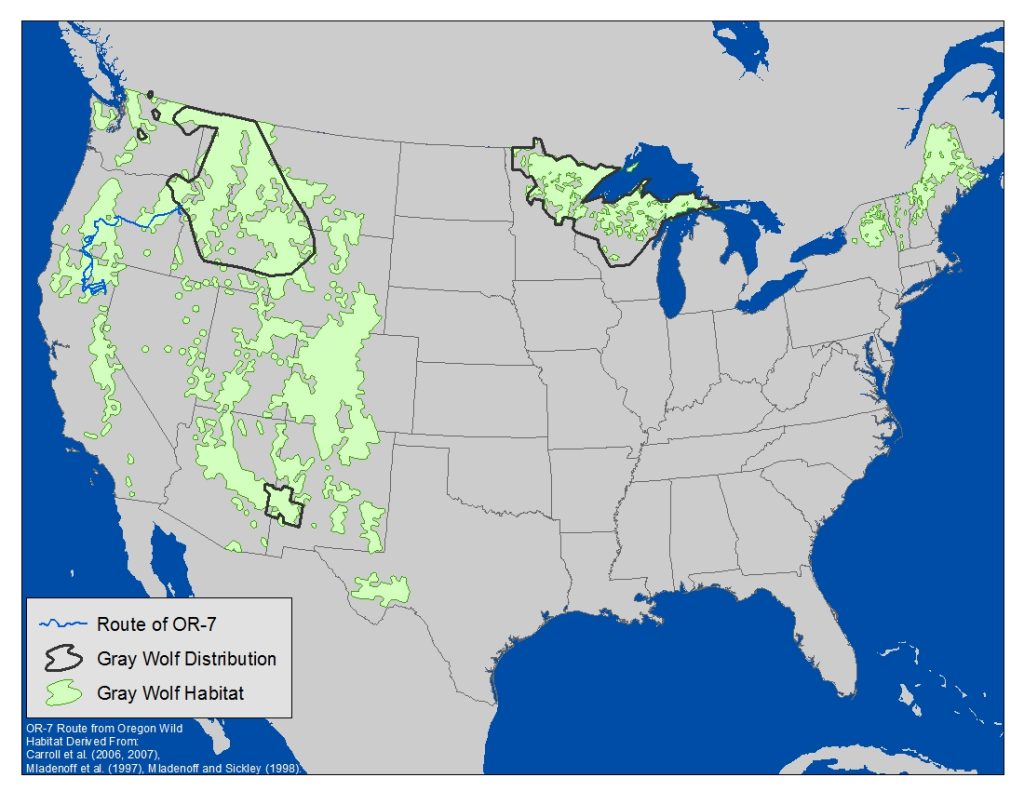

Wolves in the USA have been heavily persecuted since Europeans arrived on the continent, and as such in 1967 when they reached their minimum, there were only around 1550 individuals left. The map below shows where they still range.

Thankfully, given that most wolf subspecies has range outside the USA, we still have all of these subspecies (though the health of their population varies from subspecies to subspecies – we will cover this below in each one in turn.

The Trump administration gave the handling of the wolf population over to the states. While some took this responsibility seriously, others allowed the wolf to be all but exterminated once again.

This listing includes 5 of these subspecies, I may add or remove one as further evidence is found.

It should be noted that this image shows the layout of the wolf subspecies in north America, it does not show their current range. I have included a link to our red wolf page, it should be noted that the red wolf is not a subspecies of the grey wolf, it is a separate species which appears to be a hybrid between wolves and coyotes but split from grey wolves long in the past

Scientifically known as Canis lupus Arctus, some question the Arctic wolf classification as a subspecies, and it is certainly clear that it is only recently that wolves moved up from North America. Recent researchers have found that the Arctic wolves have no unique haplotypes (group of unique genes inherited from one parent) and that as such, they do not warrant the subspecies status, and are actually just north American wolves.

One thing to note, is that they are listed as data deficient in terms of population size, though even so, it is listed as least concern – having said this, there are clear threats. In 1997, there was a decline in the Arctic wolf population and its prey, muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus), and Arctic hares (Lepus arcticus). This was due to unfavourable weather conditions during the summers for four years. Arctic wolf populations recovered the next summer when weather conditions returned to normal. It is unclear where the information came from, but a very large number of websites list this animal as having a population of around 200,000 individuals. Given the global population of wolves is only thought to be around 200,000-250,000, there is no way that the Arctic population can be anywhere near this number. A reduction in the number of Musk ox, in recent years did also cause a decline in the Arctic wolf population.

Although quite rightly considered apex predators, polar bears will on occasion hunt arctic wolves.

While listed as least concern, they are only relatively common in Alaska where there is plenty of food. Elsewhere they are very rare. Below will show a list of any articles written on this subject. If there is anyone who is interested in writing about this species (a researcher or similar) we would be fascinated to hear, while I will endeavour to write, I have found that there is little information on this highly specialized wolf subspecies.

Click here to watch a program on this subspecies called “Following the Tundra wolf”. Unfortunately certain names are used interchangeably – here they are not talking about the Tundra wolf, but the Arctic wolf, confusingly sometimes known as the tundra wolf

Mexican wolves (scientific name is Canis lupus baileyi) are currently only found in a small area as seen on the map to the right. It is a fantastic improvement on the situation around 1970 when the species was extinct in the wild. The first reintroduction was carried out in 1998. Unfortunately, founded by just 7 individuals, the population is highly inbred. Never-the-less, currently, the USA has 257 wild Mexican wolves, while 57 live across the border in Mexico, up from just 11 that were reintroduced into the wild. A further 380 are in captivity.

Mexican wolves (scientific name is Canis lupus baileyi) are currently only found in a small area as seen on the map to the right. It is a fantastic improvement on the situation around 1970 when the species was extinct in the wild. The first reintroduction was carried out in 1998. Unfortunately, founded by just 7 individuals, the population is highly inbred. Never-the-less, currently, the USA has 257 wild Mexican wolves, while 57 live across the border in Mexico, up from just 11 that were reintroduced into the wild. A further 380 are in captivity.

As always with small populations, hybridization is a big threat. Both coyotes and other wolf subspecies can interbreed, and overlap territory in places.

If you visit an area where these wolves live, paying to do some wolf watching is the best way to support this subspecies long-term survival. If you have anything that will help with this, do click on list your wild place at the top of the page, so we can help people find you.

Tourism is one of the easiest ways to fund conservation projects, and while this species is currently not in danger, it certainly needs help to come back from its near extinction. 314 is a great population when compared to zero, but it is also a terrible one compared to the population that might exist werein not for human persecution.

The Great Plains wolf (scientific name is Canis lupus nubilus), alternatively known as the buffalo wolf or loafer, is a subspecies of gray wolf that once extended throughout the Great Plains, from southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan in Canada southward to northern Texas in the United States. The subspecies was thought to be extinct in 1926, until studies declared that its descendants were found in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan. They were described as a large, light-colored wolf but with black and white varying between individual wolves, with some all white or all black. The Native Americans of North Dakota told of how only three Great Plains wolves could bring down any sized bison.

First, described in 1828, it was thought to have been hunted to extinction in 1926, until studies declared that its descendants were found in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan. However, later studies found wolves in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Upper Michigan that were descendants of Canis lupus nubilus. Even then, their number became fewer and fewer until they were federally protected as an endangered species in 1974 (this is the same as all wolves living in the USA). Since then, their population became larger in the Great Lakes region and by 2009, their estimate grew to 2,992 wolves in Minnesota, 580 in Michigan and 626 in Wisconsin. Given the USA has a wolf popluation of 14,000-18000, a population of 4000 great plains wolves is actually significant (and more than 10 times the total population of the Mexican wolf).

Provided there is not a non-scientific return to hunting in the USA, it seems likely that they are safe for the future.

The North-western wolf (scientific name is Canis lupus occidentalis), is also known as the Mackenzie Valley wolf, Alaskan timber wolf, Canadian timber wolf or the Northern timber wolf. Arguably the largest gray wolf subspecies in the world, it ranges from Alaska, the upper Mackenzie River Valley; southward throughout the western Canadian provinces, aside from prairie landscapes in its southern portions, as well as the North-western United States. The subspecies was first described in 1829 by Scottish naturalist Sir John Richardson. He chose to give it the name occidentalis in reference to its geographic location rather than label it by its color, as it was too variable so a colour referencing name would apply to not many of the wolves in question.

According to one source, phylogenetic analyses of North American gray wolves show that there are three clades corresponding to north-western wolf, Mexican and great plains, each one representing a separate invasion into North America from distinct Eurasian ancestors. The north-western wolf, the most north-western subspecies, is descended from the last gray wolves to colonize North America. It likely crossed into North America through the Bering land bridge after the last ice age, displacing great plains wolf populations as it advanced, a process which has continued until present times. Along with great plains wolves, north-western wolves are the most widespread member of the four gray wolf subspecies in North America, with at least six different names that it goes by (I named 3 of the at the start of this article).

Currently classed as “apparently secure” (one step down from secure) , this is the subspecies that was reintroduced into Yellowstone, and has since spread to the surrounding region. Many would argue that this is the largest subspecies of wolf in the world. Unfortunately this is another subspecies, where accurate population estimates are not forthcoming.

This suggested subspecies has been in recent times, lifted to its own species status – as such I have listed it in its own species status. You can find this species on the canine page, but to look at its page now, click here

Why are wolves so fascinating?

Join as an ambassador supporter to

support this site, help save wildlife

and make friends & log in