Livestock takes up roughly 20% of the worlds land, or around 50% of the worlds agricultural land. Astoundingly, around 1.3 billion people around the world are involved in the livestock industry.

The worlds remaining land wilderness, takes up just 25% of the worlds land – should we move toa system of growing meat in labs, we could almost double the amount of space for wildlife, which would allow many of the worlds endangered species to recover.

Apart form saving so much of the worlds wilderness, and wildlife, why should we do this? Well, firstly, the fact that people want things to stay as they are, is not new. Every new invention has lead to a change in the lives of many people – before farming came into existence, all the healthy men of each village (and in places, many of the healthy women) would have spent the majority of their time hunting. Looking at the natural world, animals like lion and leopard split their time between hunting and resting, with little else (apart from reproduction) being thought of.

As electric cars started to appear, the vast majority of car companies tried to stop their progress. Indeed, many spent their time buying inventions and smaller companies, just to kill their electric car program. This was not because they were intrinsically afraid of the electric car, but because they were afraid that if adopted, they might have a smaller market share than they did with the internal combustion engine car. As tends to happen in this situation, however, many of these companies are thought likely to go out of business in the next 2 decades (and it took a start-up, Tesla to fully make electric cars work – even now, many are still trying to go back). The same can be said for the factory production line, and many many others.

The problem is that livestock farming is only second to the fossil fuel industry, in terms of its contribution to climate change, so if humanity is to survive, it needs to change dramatically.

Why should we be worried about saving the worlds wildernesses? I think that a great deal of the population feels that we should save them for their own intrinsic value, but there is more than that. Rainforests around the world are the engine that supplies much of these areas rain, and without the rainforest often the area will collapse into desert.

Some suggest that we should all go to a plant-based diet, and certainly this would do what we want (though it should be noted, that this leaves the livestock industry in the same place – indeed, the livestock industry as it currently is, must have its days numbered, as humanity cannot afford its carbon footprint or it will continue our descent into climate breakdown). The only alternative to this is to produce the dairy and meat through other means; and these means are multiplying around the world, as it is recognized that there is a lot of money available for those who solve it early.

These range from growing meat on a scaffold from cells taken from a live animal. This idea is rapidly growing in popularity, though some think that this is a dead end, and instead a lot of people are looking at brewing microbes, which can be made to have a taste and texture that will make them indistinguishable from the real thing. This would also allow the unhealthy parts like fat to be not grown. It avoids the need for a lot of land, needs no fertilizer and greatly reduces the amount of fresh water needed (some can use salt water).

Protectionism is not restricted to farmers, with many governments getting in on the act, and in the EU a new group is pushing for a continent wide ban.

I think that these things will be developed somewhere, and we will miss out, if this happens in places like China (they have a great incentive, as their population eats little real meat, but as the wealth of people are increasing, they are demanding to eat a diet more like the west. For most of us, we are going to be watching from the sidelines, in terms of what happens next, but we can write to our representatives, and make sure that livestock owners are not the only voices that they hear.

known as

known as  The

The

The giant eland, (also known as Lord Derby’s eland and greater eland) is an open-forest and savanna antelope.

The giant eland, (also known as Lord Derby’s eland and greater eland) is an open-forest and savanna antelope.

The bongo is a large, mostly nocturnal, forest-dwelling antelope, native to sub-Saharan Africa. Bongos are characterised by a striking reddish-brown coat, black and white markings, white-yellow stripes, and long slightly spiralled horns. It is the only member of its family in which both sexes have horns. Bongos have a complex social interaction and are found in African dense forest mosaics. They are the third-largest antelope in the world.

The bongo is a large, mostly nocturnal, forest-dwelling antelope, native to sub-Saharan Africa. Bongos are characterised by a striking reddish-brown coat, black and white markings, white-yellow stripes, and long slightly spiralled horns. It is the only member of its family in which both sexes have horns. Bongos have a complex social interaction and are found in African dense forest mosaics. They are the third-largest antelope in the world.

The Nyala is a spiral horned species found in Southern Africa. The nyala is mainly active in the early morning and the late afternoon. It generally browses during the day if temperatures are 20–30 °C and during the night in the rainy season. The nyala feeds upon foliage, fruits and grasses, and requires sufficient fresh water. It is a very shy animal, and prefers water holes to the river bank. Not territorial, they are very cautious creatures. They live in single-sex or mixed family groups of up to 10 individuals, but old males live alone. They inhabit thickets within dense and dry savanna woodlands. The main predators of the nyala are lion,

The Nyala is a spiral horned species found in Southern Africa. The nyala is mainly active in the early morning and the late afternoon. It generally browses during the day if temperatures are 20–30 °C and during the night in the rainy season. The nyala feeds upon foliage, fruits and grasses, and requires sufficient fresh water. It is a very shy animal, and prefers water holes to the river bank. Not territorial, they are very cautious creatures. They live in single-sex or mixed family groups of up to 10 individuals, but old males live alone. They inhabit thickets within dense and dry savanna woodlands. The main predators of the nyala are lion,  The

The

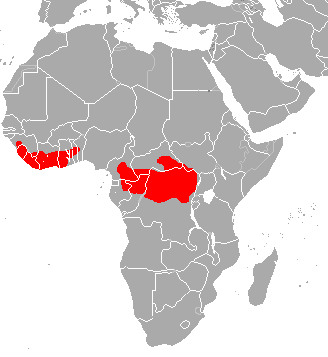

swamp-dwelling medium-sized antelope found throughout central Africa (see the map to the right. The sitatunga is mostly confined to swampy and marshy habitats. Here they occur in tall and dense vegetation as well as seasonal swamps, marshy clearings in forests, riparian thickets and mangrove swamps.

swamp-dwelling medium-sized antelope found throughout central Africa (see the map to the right. The sitatunga is mostly confined to swampy and marshy habitats. Here they occur in tall and dense vegetation as well as seasonal swamps, marshy clearings in forests, riparian thickets and mangrove swamps.