Subfamilies 3. Peleinae, 4. Alcelaphinae, 5. Hippotraginae

The subfamily 3. Peleinae (one species) (I should note, I will include a list of articles that have been (or may be in the future) for each species. I hope (in the near future) to also have a list of places to see each one will appear on the right (these will be added when they can). Obviously, many of these will not yet have any destinations, given the smaller list of places that this site lists, we hope this will grow fast.

Grey Rhebok

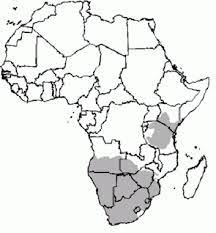

The grey rheb ok or grey rhebuck, locally known as the vaalribbok in Afrikaans, is native to South Africa, Lesotho, and Eswatini (Swaziland). The specific name capreolus is Latin for ‘little goat’. Generally confined to the higher areas of Southern Africa, they typically inhabit grassy, montane habitats – for example, sourveld – usually 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) above sea level, and carry a woolly grey coat to insulate them from the cold. They are not strictly limited to this habitat as they can be found in the coastal belt of the Cape, almost at sea level.

ok or grey rhebuck, locally known as the vaalribbok in Afrikaans, is native to South Africa, Lesotho, and Eswatini (Swaziland). The specific name capreolus is Latin for ‘little goat’. Generally confined to the higher areas of Southern Africa, they typically inhabit grassy, montane habitats – for example, sourveld – usually 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) above sea level, and carry a woolly grey coat to insulate them from the cold. They are not strictly limited to this habitat as they can be found in the coastal belt of the Cape, almost at sea level.

The grey rhebok is listed as “Near Threatened”, with a population of between 10,000-18,000

4. Subfamily Alcelaphinae - Sassabies, Hartebeest, Wildebeest (6 species)

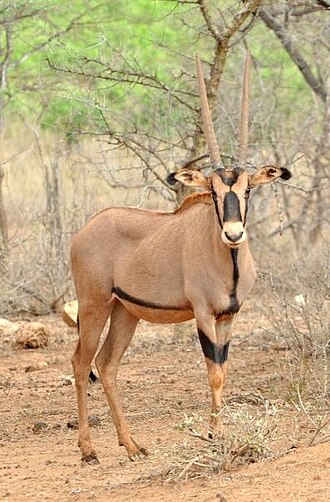

Hirola

The HIrola ( also known as the Hunters hartebeest or hunters antelope) is a critically endangered species. It was named by H.C.V Hunter (a big game hunter and zoologist) in 1888. It is the only member of the genus Beatragus, and it currently has 300-500 individuals living in the wild (there are none in captivity). It is a widely known fact, that should the Hirola be lost from the wild, it will be the last species in its genus, and therefore the first mammal genus to go extinct in Africa in the modern era. Locals have got behind this species, with 17 conservancies protecting much of the area. There are even efforts to make some of this area devoid of predators, so as to help this species bounce back faster.

The HIrola ( also known as the Hunters hartebeest or hunters antelope) is a critically endangered species. It was named by H.C.V Hunter (a big game hunter and zoologist) in 1888. It is the only member of the genus Beatragus, and it currently has 300-500 individuals living in the wild (there are none in captivity). It is a widely known fact, that should the Hirola be lost from the wild, it will be the last species in its genus, and therefore the first mammal genus to go extinct in Africa in the modern era. Locals have got behind this species, with 17 conservancies protecting much of the area. There are even efforts to make some of this area devoid of predators, so as to help this species bounce back faster.Tsessebbe, other names regularly used include Topi Sasseby and Tiang

The Tsessebbe is part of a group of so called species, which are actually subspecies (there are 5 or 6 subspecies recognized It is closest related to the Bangweulu Tsessebe, Less so, but still very close to the Topi, Korrigum, Coastal Topi and teh Tiang subspecies. Even the Bontebok is very closely related.

The Tsessebbe is part of a group of so called species, which are actually subspecies (there are 5 or 6 subspecies recognized It is closest related to the Bangweulu Tsessebe, Less so, but still very close to the Topi, Korrigum, Coastal Topi and teh Tiang subspecies. Even the Bontebok is very closely related.- Tsessebbes have around 300,000 living wild

- Korrigum (Senegalese Hartebeest) in 2004, it was numbered 2650, split between 2 national parks. They situation has not improved

- Topi are doing well with over 100,00

- Currently, the Tiang still number very high.

Bontebok

Found only in Southern Africa, its range includes South Africa, Lesotho and Namibia

There are 2 subspecies:

- Bontebok, found around the western cape -2500-3000 (vulnerable IUCN)

- Blesbok, found in the high-veld. Closely related to the Tsessebe has a population of around 120,000 (Least concern IUCN)

Hartebeest

The Hartebeest – as  many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species.

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species.

Overall, the species is listed as least concern with a population of around 360,000. The red hartebeest has a population of 130,000, but at the other end the Swaynes hartebeest in Ethiopia is only thought to number 800 in the wild. The Bulbul hartebeast (light blue) is extinct. The Lelwel Hartebeest(green) is considered endangered and has around 70,000 members. The western or Major hartebeest has around 36,000. What is clear, is that if you are travelling to an area where the local hartebeest is struggling, it would be we worth paying to see them, so as to give a value to them

Blue Wildebeest

- Other names include

common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

There has been five subspecies recognized:

C.t.taurinus (Burchell, 1823), the blue wildebeest, common wildebeest, or brindled gnu Inhabits the dark brown range

- C. t. johnstoni (Sclater, 1896), the Nyassaland wildebeest, inhabit orange (Tanzania, Mozambique Malawi)

- C. t. albojubatus (Thomas, 1912), the eastern white-bearded wildebeest, found in the Gold (beside the Yelow)

- C. t. mearnsi (Heller, 1913), the western white-bearded wildebeest, its range is shown in yellow

- C. t. cooksoni (Blaine, 1914), Cookson’s wildebeest, is restricted to the Luangwa Valley in Zambia. This is the mighter brown

In addition, the distinctive appearance of a western form, ranging from the Kalahari to central Zambia, suggests that subspecies mattosi (Blaine, 1825) may also prove distinct from subspecies taurinus. The western form can be recognised even at a distance by its upright mane, long beard, and minimal brindling.

There are around 1.5 million of this species living in the wild – so they are not endangered. Having said this, given that 1.3 million (almost 90% of them live in the Serengeti ecosystem), were something to happen, we could be in a very different position..

Black Wildebeest

The Black wildebeest is the black wildebeest or white-tailed gnu is one of the two closely related wildebeest species. It was first described in 1780 by Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann. It came surprisingly close to extinction, having been hunted as a pest and for its meat and hide.

is the black wildebeest or white-tailed gnu is one of the two closely related wildebeest species. It was first described in 1780 by Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann. It came surprisingly close to extinction, having been hunted as a pest and for its meat and hide.

The current population is now thought to be around 18,000, though 7000 of this is in Namibia (outside their natural range) where they are farmed. Their conservation status is least concern

5. Subfamily Hippotraginae

Addax

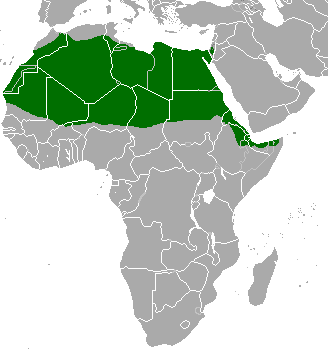

The addax , also known as the white antelope and the screwhorn antelope, is an antelope found in the Sahara Desert. The only member of the genus Addax, it was first described scientifically by Henri de Blainville in 1816. As suggested by its alternative name, the pale antelope has long, twisted horns – typically 55 to 80 cm in females and 70 to 85 cm in males. Males stand from 105 to 115 cm at the shoulder, with females at 95 to 110 cm. The females are smaller than the males (sexually diamorphic). The colour of the coat depends on the season – in the winter, it is greyish-brown with white hindquarters and legs, and long, brown hair on the head, neck, and shoulders; in the summer, the coat turns almost completely white or sandy blonde.

The addax , also known as the white antelope and the screwhorn antelope, is an antelope found in the Sahara Desert. The only member of the genus Addax, it was first described scientifically by Henri de Blainville in 1816. As suggested by its alternative name, the pale antelope has long, twisted horns – typically 55 to 80 cm in females and 70 to 85 cm in males. Males stand from 105 to 115 cm at the shoulder, with females at 95 to 110 cm. The females are smaller than the males (sexually diamorphic). The colour of the coat depends on the season – in the winter, it is greyish-brown with white hindquarters and legs, and long, brown hair on the head, neck, and shoulders; in the summer, the coat turns almost completely white or sandy blonde.

The addax mainly eats grasses and leaves of any available shrubs, leguminous herbs and bushes and can survive with no more water than that in the plants they eat for long periods of time. Addax form herds of 5to 20 members, consisting of both males and females, but they are led by the eldest female. Due to its slow movements, the addax is an easy target for its predators: humans, lions, leopards, cheetahs and African wild dogs. Breeding season is at its peak during winter and early spring. The natural habitat of the addax are arid regions, semideserts and sandy and stony deserts.

The addax is a critically endangered species of antelope, as classified by the IUCN (though the USFWS lists them as endangered, as the population is thought to have gone from under 100 to around 500 in the last few years) . Although extremely rare in its native habitat due to unregulated hunting, it is quite common in captivity. The addax was once abundant in North Africa; however it is currently only native to Chad, Mauritania, and Niger. It is extirpated from Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Sudan, and Western Sahara, but has been reintroduced into Morocco and Tunisia. On the map, they green areas are where they still live, while the red represent places that they have been reintroduced

Sable Antelope

Known for its impressive back curving horns, the sable antelope is a large antelope which inhabits wooded savanna in East and Southern Africa, from the south of Kenya to South Africa, with a separated population in Angola.

Known for its impressive back curving horns, the sable antelope is a large antelope which inhabits wooded savanna in East and Southern Africa, from the south of Kenya to South Africa, with a separated population in Angola.

There are 4 subspecies

- The southern sable antelope (other names include the common sable antelope, black sable antelope, Matsetsi sable antelope or South Zambian sable antelope) was the first to be described in 1838 and so is considered the nominate subspecies. Often referred to as the black sable antelope because it tends to have the darkest coat, this subspecies occurs south of the Zambezi River, particularly in northern Botswana and in large numbers in the Matsetsi Valley of Zimbabwe, but it is also found in South Africa. Currently, only about 15% pure Matsetsi sable antelopes are thought to exist in South Africa. The Matsetsi sable antelope population in Zimbabwe is only 450 (down from 24,000 in 1994). The sable antelope population in South Africa is about 7,000 (commercial and in reserves). Therefore, the Matsetsi sable antelope population apparently is less than 1,500 and declining. However, most of the sable antelope in the reserves are pure Matsetsi sable antelope. Anglo-American recently started a program of breeding pure Matsetsi sable antelope commercially and keeping them pure.

- The giant sable antelope (also known as the royal sable antelope) is so named because both sexes are larger and their horns are recognizably longer. It is found only in a few remaining localities in central Angola. It is classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List and is listed on Appendix I of CITES. There are thought to be less than 1000 left in the wild. Given a war raged for 27 years (ending in 2002), there is little tourism to the country. If this changes it is likely to give impetus for protecting what wildlife that remains.

- The Zambian sable antelope (also known as the West Zambian sable antelope or West Tanzanian sable antelope) has the largest geographic range of the four subspecies, which extends north of the Zambezi River through Zambia, the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and Malawi into southwestern Tanzania. It is classified as Vulnerable (I cannot find a population estimate.

- The eastern sable antelope (also known as the Shimba sable antelope) is the smallest of the four subspecies. It occurs in the coastal hinterlands of southern Kenya, particularly in the Shimba Hills National Reserve, and ranges through the region east of Tanzania’s eastern escarpment and into northern Mozambique.

In English “great sable antelope”, “sable” or the Swahili name mbarapi are sometimes used. An archaic term used in accounts of hunting expeditions in South Africa is “potaquaine”; the origin and exact application are unclear. Local names include swartwitpens (Afrikaans), kgama or phalafala (Sotho), mBarapi or palahala (Swahili), kukurugu, kwalat or kwalata (Tswana), ngwarati (Shona), iliza (Xhosa), impalampala (Zulu) and umtshwayeli (Ndebele).

Roan Antelope

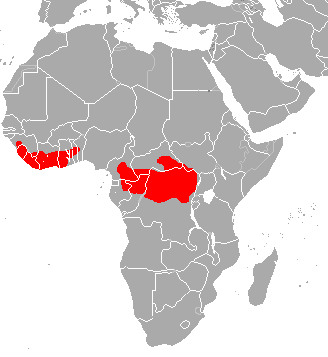

The roan antelope is a large savanna-dwelling antelope found in western, central, and southern Africa. Named for its roan colour (a reddish brown), it has lighter underbellies, white eyebrows and cheeks and black faces, lighter in females. It has short, erect manes, very light beards and prominent red nostrils. It is one of the largest antelope, measuring 190–240 cm from head to the base of the tail, and a 37–48 cm long tail. Males weigh 242–300 kg and females 223–280 kg . Its shoulder height is around 130–140 cm.

The roan antelope is a large savanna-dwelling antelope found in western, central, and southern Africa. Named for its roan colour (a reddish brown), it has lighter underbellies, white eyebrows and cheeks and black faces, lighter in females. It has short, erect manes, very light beards and prominent red nostrils. It is one of the largest antelope, measuring 190–240 cm from head to the base of the tail, and a 37–48 cm long tail. Males weigh 242–300 kg and females 223–280 kg . Its shoulder height is around 130–140 cm.

It was first described by French naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire in 1803. It is listed as least concern by IUCN, while CITES places them on appendix 3 (I have been unable to find conservation of the subspecies, but these will be added if/ when I do.

Six subspecies are recognised:

- H. e. bakeri (Heuglin, 1863): Occurs in Sudan (East Africa). Vulnerable

- H. e. cottoni Dollman and Burlace, 1928: Occurs in Angola, Botswana, the southern Democratic Republic of the Congo, central and northern Malawi, and Zambia (Southern Africa).

- H. e. equinus É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1803: Occurs in Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe (Southern Africa).

- H. e. koba (Gray, 1872): Range extends from Senegal to Benin (West Africa).

- H. e. langheldi Matschie, 1898: Occurs in Burundi, the northern Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda (East Africa).

- H. e. scharicus (Schwarz, 1913): Occurs in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad and eastern Nigeria (Central Africa).

Gemsbok

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

The name gemsbok is from Afrikaans, which itself is from the Dutch word of the same spelling, meaning “male chamois”, composed of gems (“chamois”) + bok (“buck, male goat”).

It is on the Namibian coat of arms, as there are roughly 373,000 in the country. They are listed as least concern. Being a desert species, they are only found in South African reserves in the west, and are not found in the Kruger. The closely related East African Oryx lives (unsurprisingly) in east Africa.

Beisa Oryx - Also known as the East African Oryx

The East African oryx inhabits eastern Africa. The East African oryx has two subspecies;

- the common beisa oryx (O. b. beisa)

- the fringe-eared oryx (O. b. callotis).

In the past, both were considered subspecies of the gemsbok. The East African oryx is an endangered species, with 11,000-13,000 mature individuals in the wild.

Scimitar Oryx

The scimitar oryx, also called the scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah), of North Africa used to be listed as extinct in the wild, but it is now declared as endangered. Unconfirmed surviving populations have been reported in central Niger and Chad, and a semi-wild population currently inhabiting a fenced nature reserve in Tunisia is being expanded for reintroduction to the wild in that country. Several thousand are held in captivity around the world.

6. Subfamily Aepycerotinae (1 species)

Impala

There are currently around 2 million Impala roaming across Africa. About one quarter of these live in protected areas in Botswana, Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Around 1000 of the Black faced Impala live in the green area in the west of Africa.

Impala roaming across Africa. About one quarter of these live in protected areas in Botswana, Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Around 1000 of the Black faced Impala live in the green area in the west of Africa.

In some reserves such as the Kruger, they are the most common antelope.

7. Subfamily Antilopinae

Dama Gazelle

The Dama Gazelle is a small antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

In Niger, the Dama Gazelle has become a national symbol.

There are 3 subspecies, however the Mhorr gazell is extinct in the wild (though zoos have a number) , the dama gazelle is only kept in captivity one zoo and is very rare in the wild.

The species is critically endangered with only 100-200 left in the wild. Given that this small population is spread over a number of areas. The number of wild semi wild and captive is around 2900, so it is just the need to save the species in the wild which is the current problem.

Dorcas Gazelle

There are currently around 35,000-40,000 dorcas gazelle roaming across the whole of north Africa (though given this large range they are not particularly numerous in any location). It is unclear how many of these live in protected areas. Some whole countries like Sudan still have these animals but no reserves. in Algeria, Chad, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Israel, Jordan, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Somalia, Sudan, Tunisia, Western Sahara. There are 7 subspecies-

There are currently around 35,000-40,000 dorcas gazelle roaming across the whole of north Africa (though given this large range they are not particularly numerous in any location). It is unclear how many of these live in protected areas. Some whole countries like Sudan still have these animals but no reserves. in Algeria, Chad, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Israel, Jordan, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Somalia, Sudan, Tunisia, Western Sahara. There are 7 subspecies-

- Eritrean Dorcas Gazelle or Heuglin’s gazelle (Eritrea, Ethiopia and Sudan): 2500-3500 in the wild. Populations fell around 20% between 2008 and 2016 (unknown what happened since)

- Egyptian Dorcas Gazelle – status unknown

- Isabelle Dorcas Gazelle – status unknown

- Moroccan Dorcas gazelle – Isolated in the M’Sabih Talaa reserve in Morocco for 50 years. Its biggest threats appear to be feral dogs and poaching. Due to factors like this, the population has halved in 15 years,recently. Population numbered 209 in 1987. The most recent survey suggested 100 (in 2013). What has happened in the last 11 years has not been ascertained.

- Saharan (or Saharawi) dorcas gazelle

Gerenuk

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

They are currently classed as not threatened, and have a wild population of around 95000.

Two subspecies are recognized:

- Northern gerenuk or Sclater’s gazelle (Its range extends from north-western Somalia westward to touch the Ethiopian border and Djibouti.

- Southern gerenuk or Waller’s gazelle (Its range extends through north-eastern Tanzania through Kenya to Galcaio (Somalia). The range lies north of the Shebelle River and near Juba River.)

Grant's Gazelle

There are currently around 140,000-300,000 Grant’s gazelle roaming through parts of East Africa and in places like the Serengeti are a common sight. It is unclear how many of these live in protected areas. They can be found from southern Sudan and Ethiopia to central Tanzania and from the coast of Kenya and Somalia to Lake Victoria. They are currently classed as unthreatened. There are 3 subspecies-

There are currently around 140,000-300,000 Grant’s gazelle roaming through parts of East Africa and in places like the Serengeti are a common sight. It is unclear how many of these live in protected areas. They can be found from southern Sudan and Ethiopia to central Tanzania and from the coast of Kenya and Somalia to Lake Victoria. They are currently classed as unthreatened. There are 3 subspecies-

- Northern Grant’s Gazelle (Ethiopia and Kenya)

- Southern Grant’s Gazelle – East Africa and found from Central Kenya up to the Samburu Game Reserve down to southern Tanzania around Ruaha National Park.

- Robert’s grants Gazelle – only found in the Serengeti/Mara ecosystem (it is unclear how many of these gazelles live here, but a total of 500,000 Thompsons and Grant gazelles live in the whole ecosystem

Mhorr Gazelle

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

They are currently classed as not threatened, and have a wild population of around 95000.

Two subspecies are recognized:

- Northern gerenuk or Sclater’s gazelle (Its range extends from north-western Somalia westward to touch the Ethiopian border and Djibouti.

- Southern gerenuk or Waller’s gazelle (Its range extends through north-eastern Tanzania through Kenya to Galcaio (Somalia). The range lies north of the Shebelle River and near Juba River.)

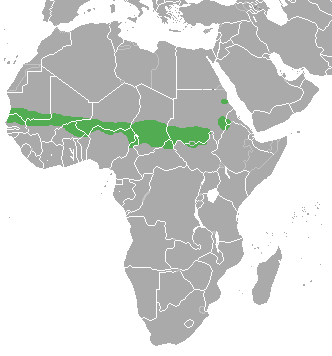

Red-fronted Gazelle

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle.

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle.

- Eastern Chad red-fronted gazelle

- North Nigeria red-fronted gazelle

- Kanuri red-fronted gazelle

- Nubian red-fronted gazelle

- Senegal red-fronted gazelle

Slender-horned Gazelle

Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

- G. l. leptoceros F. Cuvier, 1842 (none in captivity) from Egypt and Libya (north-east) as well as possibly Chad and Niger.

- G. l. loderi Thomas, 1894 found in Algeria and Tunisia and western Libya

The split between the two subspecies is not well defined. It should be noted that the red list states that there is more than 250 but it may be not that far above. One or both of these subspecies may well be incredibly close to extinction. It should be noted, that even a population of just 250 in the two subspecies, should these two subspecies be in one population each, it could well recover relatively fast.

It is hard to see this species surviving long-term unless poaching stops and perhaps even requiring the amalgamation of all the populations of each subspecies (indeed, we may well be beyond the sensible attempt to save each subspecies and but to merely concentrate on saving the species as a whole.

Soemmerring's Gazelle

Also known as the Abyssinian mohr, it is a gazelle species native to the Horn of Africa which includes Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia and South Sudan (possibly no longer present here). The species was first described by German physician Philipp Jakob Cretzschmar in 1828. Three subspecies are recognized, which include

- Nubian Soemmerring’s gazelle (Cretzschmar, 1828)

- Somali Soemmerring’s gazelle (Matschie, 1893)

- Borani Soemmerring’s gazelle (Thomas, 1904)

- The dwarf population on Dahlak Kebir island might also qualify as a subspecies.

They are classed as vulnerable with a wild population of roughly 6000-7500 with the largest single population being on Dahlak Kebir which is part of Eritrea (this country is estimated to have a population of 3000-4000 (between 40-65% of the worlds population. It has been classed as vulnerable to extinction since 1986, however I would argue that its future survival is probably less good than that sounds. Being largely a desert species, it might be hard to see, but there will still be places where it is found, and as always, a visit should help give the live species more local value.

Speke's Gazelle

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

At the current time, there is no reserve within the Speke’s gazelles range, making it hard to see them (this is largely as a result of their remaining reserve likely being exclusively found in Somalia, where war has raged for a very long time.

Springbok

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

Three subspecies recognized

- A. m. angolensis (Blaine, 1922) – Occurs in Benguela and Moçâmedes (southwestern Angola).

- A. m. hofmeyri (Thomas, 1926) – Occurs in Berseba and Great Namaqualand (southwestern Africa). Its range lies north of the Orange River, stretching from Upington and Sandfontein through Botswana to Namibia.

- A. m. marsupialis (Zimmermann, 1780) – Its range lies south of the Orange River, extending from the northeastern Cape of Good Hope to the Free State and Kimberley.

There are 2,000,000-2,500,000 remaining in the wild.

Thompson Gazelle

Approximately 550,000 Thompson gazelles remain in the wild, with the largest population being found in the Serengeti Mara ecosystem. Named after Joseph Thompson an explorer, some consider it a subspecies of the red-fronted gazelle.

Approximately 550,000 Thompson gazelles remain in the wild, with the largest population being found in the Serengeti Mara ecosystem. Named after Joseph Thompson an explorer, some consider it a subspecies of the red-fronted gazelle.

It is the fourth fastest land animal, after cheetah (its main predator) springbok and pronghorn, and can hit speeds of 80-90km per hour.

Two subspecies are identified:

- E. t. nasalis (Lönnberg, 1908) – Serengeti Thomson’s gazelle ranges from the Serengeti to the Kenya Rift Valley.

- E. t. thomsonii (Günther, 1884) – eastern Thomson’s gazelle ranges from east of the Rift Valley in Kenya and Tanzania, southward to Arusha District (Tanzania) and then southwestward to Lake Eyasi, Wembere River, and Shinyanga.

Dibatag

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

No reserves protects any of this population. The population is definitely under 10000 and probably under 4000. Their range is also restricted to a 100km by 100km area.

The dibatag is endemic to the evergreen bushland of the Ogaden region of southeastern Ethiopia and adjoining parts in northern and central Somalia. In the past their range extended from the southern parts of northern Somalia through southeastern Ethiopia and central Somalia (between the coastline of the Indian Ocean and bounded by the Fafen River in the west and the Shebelle River in the southwest). Rock paintings of two dibatag were discovered on the west bank of the river Nile and north of the Aswan Dam in Egypt, suggesting a southward migration of the species in the Predynastic period in Egypt.

Bate's Pygmy Antelope

Also known as the pygmy antelope, and the dwarf antelope, it is classed as least concern, and is considered fairly common (a precise estimate is not available).

Also known as the pygmy antelope, and the dwarf antelope, it is classed as least concern, and is considered fairly common (a precise estimate is not available).

While the species is suffering from habitat loss which means that their future is not necessarily good. In general, they are able to adapt to secondary forest, plantations, roadside verges and village gardens. Although not hunted commercially, this antelope is hunted for bushmeat in limited numbers.

Beira

Living in the arid regions of the horn of Africa, this species is classed as vulnerable. Unfortunately, as with other species living in this region, there is little protected land, so this situation may get worse in the near future.

As with others on this list means that while grazing is the normal, they will to browse where it is necessary.

Cape Grysbok

Only found along the extreme southern coast of South Africa, the Cap Grysbok is classed as least concern with a population that is unknown, but is estimated at an upper level of over 200,000, and so it is listed as least concern.

Guenther's Dikdik

Guenthers dikdik is another species only found within the horn of Africa and some areas around here. It is classed as least concern, and while there has been 4 subspecies suggested based on looks, no-one has yet looked in more detail to see if this is correct.

The species is found in the lowlands of Ethiopia, most of the northern and eastern regions of Kenya, Somalia excluding specific regions of the coast, limited regions of southeastern Sudan, and north-eastern Uganda. They avoid coastal regions. Typical habitat includes low thicket-type vegetation in thornbush, savanna grassland and riverine woodland biomes, and extends to disturbed and overgrazed areas. Habitat overlaps with other small antelope species such as Kirk’s dik-dik (a similar species which I have encountered in Kenya).

There are a number of protected areas within its range, meaning that its future is more secure than other species that share at least part of its range. The population is estimated at roughly 511,000 individuals.

Kirk's Dikdik

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

They are classed as least concern, suggesting that at the current time, they are doing well. I have seen these in northern Kenya, and they have an adorable habit of traveling around in pairs. So strong is their bond, that if one leaps out into the road, it is well worth breaking hard, as the other one is highly likely to follow shortly after. They can live in relatively high densities, though changes in predator can make large differences fast. A small reserve I stayed on in northern Kenya, had had a wild dog pack move onto the land. In one year, they had reduced the number of dik-diks by roughly half.

The overall population of this species is thought to be around 971,000.

Klipspringer

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places.

It is closely related to the kirks dikdik (above) and the Oribi (below). Mainly active at night, it spends its days resting. It is mainly a browser, feeding on young plants fruits and flowers. They are classed as least concern, and as much of their population is in relatively unfavourable land, rarely hunted. In 2008, an assessment suggested that only 25% of the population live within protected areas. This means that although currently not remotely threatened, this would be an easy species for this to change.

Their population is estimated at around 40,000, though given the large area in which these are found, their distribution is likely to be sparse at best. Finding them, in an area where we know they are, however, is not normally hard – certainly in places like the Kruger they are a relatively easy find.

Given the holes in this species range, it is reasonable to suppose that historically there were more of this species, but if there were, it is likely quite some time ago.

Oribi

A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

Their wild population is estimated at 750,000 so are listed as least concern, but this is only an estimate, and they are thought to be declining.

Royal Antelope

This is officially classed as the worlds smallest antelope, standing only 25cm tall at the shoulder, and weighing 2.5kg

Usually active at night, it marks its territory with dung, and is very alert. An herbivore, the royal antelope prefers small quantities of fresh foliage and shoots; fruits and fungi may be taken occasionally. Like other neotragines, the royal antelope is monogamous (capable of having young as early as 6 months old). Births have been reported in November and December. A single, delicate young is born after an unknown gestational period.

In 1999, its population was estimated at 62,000, but this could be an underestimate.

Salt's Dikdik

This species is found in the area marked on the map.

5 subspecies are recognized

- M. s. saltiana is found from northern Ethiopia to Eritrea and far eastern Sudan, and is relatively large with a reddish-grey back.

- M. s. hararensis is found in the Hararghe region in eastern Ethiopia, and has a gingery back and dark red flanks.

- M. s. lawrenci is found in eastern and southeastern Somalia, and has a silvery back and russet flanks.

- M. s. phillipsi is found in Somaliland, and its back is grey and flanks are orange.

- M. s. swaynei is found in the Jubba Valley region of southern Ethiopia, southern Somalia, and far northern Kenya; its back is brown-grey.

Sharpe's Grysbok

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice.

It has an estimated 95,000 individuals in the wild and is listed as least concern. Around 1/3 of the population lives within protected ares.

Steenbok

The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

There are 650,000 estimated to still live in the wild, and they are classified as least concern.

On the map, you can see where this species is found, however this is also a list of countries where you can find this species. In East Africa, it occurs in central and southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. It was formerly widespread in Uganda, but is now almost certainly extinct there. In Southern Africa, it occurs in Angola, Namibia, South Africa, Eswatini, Botswana, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbabwe and probably Lesotho. There are 2 subspecies recognized (though as many as 24 have been suggested based on colouring and similar)

Silver Dikdik

Found in dense thickets along the southeastern coast of Somalia and in Acacia-Commiphora bushland in the Shebelle Valley in southeastern Ethiopia, it is listed as data deficient (not surprising given where it originates. It is unfortunately a fact, however, that the majority of species which are found in this area, are in a desperate state. It is true that for many species they do better, when no-one is paying any attention. For instance, the mountain gorilla population grew enormously during the war, as there was to much danger to poach them, although there was also no tourism revenue coming in.

While its weight and size is similar to a domestic cat, While the last estimate was in 1999, with the population put at 30,000, the range has been expanded since (though unfortunately the 30,000 is still probably am over estimate 25 years ago. The likelyhood of this species population growing in this time, is low.

Suni

The Suni is a small species of antelope found from Kenya down to northern South Africa (it is also found on Zanzibar which is off the coast of Tanzania).

The Suni is a small species of antelope found from Kenya down to northern South Africa (it is also found on Zanzibar which is off the coast of Tanzania).

The Suni is listed as least concern, and the last time a population estimate was made (1999), they came up with a number of 365,000, a sizeable number (though given the range of this animal, it is not a huge number).

There are 4 subspecies (though some claim these as 4 separate species)

- Coastal suni — N. m. moschatus (Von Dueben, 1846) — found on the Zanzibar Archipelago (Changuu and Chapwani islands; Jozani, Kendwa, Kizimkazi and Nungwi, Unguja) and coastal Kenya (Arabuko Sokoke Park, Mombasa, Watamu).

- Livingstone’s suni — N. m. livingstonianus (Kirk, 1865) — South Africa (KwaZulu-Natal), Malawi, inland Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

- Mountain suni — N. m. kirchenpaueri (Pagenstecher, 1885) — Kenya (Aberdare Range, Karura Forest, Mount Kenya, Nairobi National Park) and Tanzania (Arusha National Park).

- Southern suni — N. m. zuluensis (Thomas, 1898) — South Africa (KwaZulu-Natal, Hluhluwe-Imfozoli, iSimangaliso Wetland Park), Eswatini (Mkhaya Game Reserve), and coastal southern Mozambique (Ponta do Ouro and surrounding areas).

This species population has definitely been reduced by poaching, though they are still abundant. In South Africa, many are killed by dogs.

Abbott's Duiker

Known as Minde in Swahili is a large forest duiker found in a few small areas of Tanzania (Abbott’s duiker is endemic to Tanzania, in the Eastern Arc Mountains, Mount Kilimanjaro, and Southern Highlands in scattered populations.). There has been some debate about whether this is a separate species or whether it is a subspecies of the yellow-backed duiker. It should be noted that it is only rarely seen, and was only first photographed in 2003.

Known as Minde in Swahili is a large forest duiker found in a few small areas of Tanzania (Abbott’s duiker is endemic to Tanzania, in the Eastern Arc Mountains, Mount Kilimanjaro, and Southern Highlands in scattered populations.). There has been some debate about whether this is a separate species or whether it is a subspecies of the yellow-backed duiker. It should be noted that it is only rarely seen, and was only first photographed in 2003.

They are estimated to have 1500 individuals in the wild, but are threatened by habitat destruction and poaching.

Aders's Duiker

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

The Zanzibar population dropped from 5000-640 between 1983 and 1999, and is estimated to be as low as 300 now (or as high as 600 – the estimates have wide ranges).

Bay Duiker

The bay duiker has a distribution across central and western Africa, and is restricted to areas of rainforest. Also known as the black striped duiker or the black backed duiker. For this duiker family, they are relatively tall, standing at 45-50cm at the shoulder, and weigh 18-23kg.

It is nocturnal and either solitary or living in pairs. Its natural main predator is the leopard, it has been historically over harvested for the bushmeat trade, and loss of habitat for both agriculture and housing has affected it. Never-the-less, its population is still listed as near threatened. Given its ability to sustain despite large quantities of hunting from both humans and leopards, its greatest threat is the loss of the Congo rainforest (unfortunately the greatest threat for many species).

Black Duiker

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

Black duikers live mainly in lowland rainforest, where they eat fruit, flowers, and leaves which have fallen from the canopy. They are probably diurnal (active during the day), though this has only been worked out from captive specimens (an unreliable system, as many animals have different habits in the wild to in captivity. Black duiker are reported to be solitary, territorial animals. While most young are born between November and January, mating can occur any time of year, and pregnancy lasts roughly 4 months.

Lifespan is not clear in the wild, but in captivity they can live 14 years.

Black-fronted Duiker

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams. The black-fronted duiker is territorial and monogamous, each pair owning a territory that it defends against neighbours and is marked using the secretions of the facial glands. The pair have habitual paths within their territory that connect sleeping sites with feeding areas and allow them to be active during both day and night. They are mainly browsers but will also feed on fruit. The currently recognised subspecies are:

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams. The black-fronted duiker is territorial and monogamous, each pair owning a territory that it defends against neighbours and is marked using the secretions of the facial glands. The pair have habitual paths within their territory that connect sleeping sites with feeding areas and allow them to be active during both day and night. They are mainly browsers but will also feed on fruit. The currently recognised subspecies are:

- Cephalophus nigrifrons fosteri St. Leger, 1934

- Cephalophus nigrifrons hooki St. Leger, 1934

- Cephalophus nigrifrons hypoxanthus Grubb and Groves, 2002

- Cephalophus nigrifrons kivuensis Lönnberg, 1919

- Cephalophus nigrifrons nigrifrons Gray, 1871 .

- Cephalophus nigrifrons rubidus Thomas, 1901: Known as the Ruwenzori duiker

Blue Duiker

The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

It is currently listed as least concern, but is quite a common source of bushmeat, and as such it is under threat from local extinction. As you can see from the map, its range is quite patchy – while this is partly a result of where woodland is found, it is also likely a result of local extinction.

It is listed as least concern, and is thought to have around 7 million left in the wild.

Grey duiker (common)

Also known as the common or bush duiker. It is found throughout almost all of Africa, south of the Sahara.

According to the IUCN Red List, the total Common duiker population size is around 1,660,000 individuals, however, other research has suggested that the total population size of this species is approximately 10 million individuals. This is obviously a far too wide range to have.

I would argue that the population is likely nearer the higher end. If it is not, this species should no longer be listed as common, given species like the blue duiker would be far more common.

Given its wide range, there are many reserves to see this species. I have seen this species in Kruger national park.

Harvey's Red duiker (Harvey's duiker)

The Harvey’s red duiker is found in Tanzania and scattered through Kenya, southern Somalia and possibly central Ethiopia. They stand roughly 40cm tall and weigh around 15kg. They are mostly chestnut coloured, but has black legs.

Harvey’s duikers live in mountain and lowland forest, where they eat leaves, twigs, fruit, insects, birds eggs, and carrion. Although this duiker is not endangered, it is dependent on protected forestland. As of 2008, this species is of least concern. Total population is roughly 20,000. It is classed as least concern, which suggests that 20,000 is close to the original population size, from where it is found.

Jentink's Duiker

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink.

Recent population numbers are not available. In 1999 it was estimated that around 3,500 Jentink’s duikers remained in the wild, but the following year others suggested less than 2,000 were likely to remain, unfortunately another estimate has not been made in the 25 years since. It is likely that the population did not drop 1500 in a year, but was over counted the first time. Either way this is a small population, but if the drop was that fast, it would be worse than it is currently thought. They are threatened primarily by habitat destruction and commercial bushmeat hunters. They are classed as endangered, but clearly need more information, and I would argue that are more naturally falling into the class of data deficient.

Maxwell's Duiker

A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

Three subspecies are identified:

- P. m. danei or P. m. lowei Hinton, 1920 Occurs in Sierra Leone.

- P. m. maxwelli C. H. Smith, 1827 Occurs in Senegal, Gambia and Sierra Leone.

- P. m. liberiensis Hinton, 1920 Occurs in Liberia, Ghana and further East

Natal Red-duiker

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

The last estimate of the population was in 1999, when it was estimated at 42,000.

They are also listed as least concern

Ogilby's Duiker

The two former subspecies, the white-legged duiker Cephalophus crusalbum and the Brooke’s duiker Cephalophus brookei, are considered as distinct species since 2011.

The two former subspecies, the white-legged duiker Cephalophus crusalbum and the Brooke’s duiker Cephalophus brookei, are considered as distinct species since 2011.

Measuring 56cm at the shoulder and weighing up to 20kg, they mainly live mainly in high-altitude rainforests, where they feed mainly on fallen fruit.

They are estimated at 12,000 and are listed as least concern

Peter's Duiker

The Peters duiker is a species found in a region of west African rainforest (see map) living in Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, southern Cameroon, and northern Republic of the Congo. It weighs 18kg and measures 50cm at the shoulder.

The Peters duiker is a species found in a region of west African rainforest (see map) living in Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, southern Cameroon, and northern Republic of the Congo. It weighs 18kg and measures 50cm at the shoulder.

There are an estimated 380,000 in the wild and is declining.

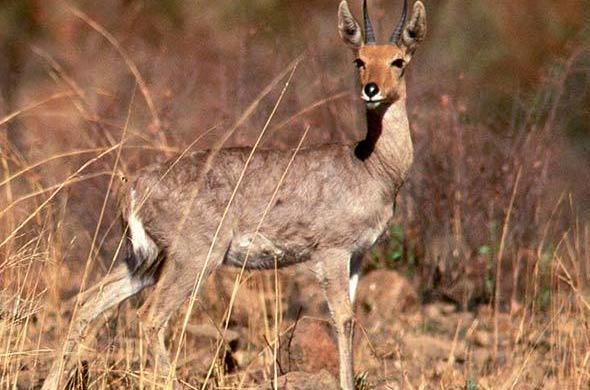

Red-flanked Duiker

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

White-bellied duiker

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda.

They are classed as not threatened, and have more than 250,000 in the wild.

Yellow-backed Duiker

The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

They are classed as near threatened, with 160,000

Four subspecies are recognized:

- C. s. curticeps Grubb and Groves, 2002

- C. s. longiceps Gray, 1865

- C. s. ruficrista Bocage, 1869

- C. s. silvicultor (Afzelius, 1815)

Zebra Duiker

The zebra duiker is a small antelope found primarily in Liberia, as well as the Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone, and occasionally Guinea. They are sometimes referred to as the banded duiker or striped-back duiker. It is believed to be one of the earliest duiker species to have evolved.

Its wild population is estimated at 28,000 and is classed as vulnerable

They are predated on by a range of species including leopards, African golden cats, rock pythons, and the crowned eagle. They are considered Vulnerable by the IUCN due to deforestation, loss of habitat, and overhunting within its range (bush meat).

Walter's Duiker

Measuring 40cm at the shoulder and weighing 4-6kg it was initially described from a bush-meat specimens in 2010 from Togo. It was not seen in the wild until 2021 when it was caught on camera trap. The are believed to come from the Dahomey Gap, an area of savannah which is a portion of the Guinean forest-savanna mosaic with a relatively dry climate, that extends all the way to the coast in Benin, Togo and Ghana, separating the rainforest zones on either side.

Understandably however, they are classed as data deficient. There is a big concern at the current time, with so little information, that they may get pushed to extinction without fully understanding where they are or what they need in order to survive in the wild.

Having only been photographed once in the wild, there are no animals in zoos, and so should they be lost from the wild, they will be gone for good.

The Capra family (goats sheep and Ibex)

Arabian Tahr

The Arabian Tahr is a species of Tahr found in eastern Arabia. They were recently moved to their own genus Arabitragus. It is the smallest Tahr species, and both genders have rear facing small horns. They have longish fur of redish brown fur, with a black stripe running down its back. They live in the Hajar Mountains in Oman and the United Arab Emirates, at evelation of up to 1800m.

The Arabian Tahr is a species of Tahr found in eastern Arabia. They were recently moved to their own genus Arabitragus. It is the smallest Tahr species, and both genders have rear facing small horns. They have longish fur of redish brown fur, with a black stripe running down its back. They live in the Hajar Mountains in Oman and the United Arab Emirates, at evelation of up to 1800m.

Its wild population is estimated at 2,200 and at the current moment is listed as endangered.

They are predated on by a range of species including leopards, African golden cats, rock pythons, and the crowned eagle. They are considered Vulnerable by the IUCN due to deforestation, loss of habitat, and overhunting within its range (bush meat).

Barbary Sheep

The Barbary Sheep, is found in a variety of locations across northern Europe. Biggest populations include Spain, with around 50,000 after being introduced in the 1970s. Algeria has a native population of several thousand, with the Tunisian population though to number in just several hundred.

The Barbary Sheep, is found in a variety of locations across northern Europe. Biggest populations include Spain, with around 50,000 after being introduced in the 1970s. Algeria has a native population of several thousand, with the Tunisian population though to number in just several hundred.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there are a range of subspecies as a result of such a large geographic range. All are vulnerable, except the second, which has a population in Egypt, but outside its historical range – so, it is classed as “extinct in the wild”. The IUCN red list, however, suggests a population of 5000-10,000. This seems far too big, given these numbers, with the population within historical range likely being under 2500.

- A. l. angusi Rothschild, 1921

- A. l. blainei Rothschild, 1913

- A. l. lervia Pallas, 1777

- A. l. fassini Lepri, 1930

- A. l. ornatus I. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1827

- A. l.sahariensis Rothschild, 1913

Barbary sheep are found in arid mountainous areas where they graze and browse grasses, bushes, and lichens. They are able to obtain all their metabolic water from food, but if liquid water is available, they drink and wallow in it. Barbary sheep are crepuscular – active in the early morning and late afternoon and rest in the heat of the day. They are very agile and can achieve a standing jump over 2 metres. They are well adapted to their mountainous habitat. They often flee at the first sign of danger, typically running uphill. They are extremely nomadic and travel constantly via mountain ranges. Their main predators in North Africa were the Barbary leopard (not seen since 1990), Barbary lion (possibly extinct since 1942 at their last sighting, certainly since the 1960s), and caracal (still found, but near extinction), but now humans, feral dogs, competition due to overgrazing by domestic animals and drought threaten their populations.

The Bharal is found in the high Himalayas.It is split into 3 subspecies

The Bharal is found in the high Himalayas.It is split into 3 subspecies

- Chinese blue sheep, Pseudois nayaur szechuanensis

- Himalayan blue sheep, P. n. nayaur

- Helan Shan blue sheep, P. n. ssp.

The darker blue area on the map is the range of the dwarf Bharal, thought, until a 2012 genetic study to be a separate species. However, it was found to be too genetically similar to even rise to the level of subspecies.

They are active during the day, and alternate between feeding and resting. A high degree of diet overlap between livestock (especially donkeys) and bharal, together with density-dependent forage limitation, means that they have lower density, in areas close to human settlements.

They are regular prey (when lambs) of both fox and eagle. When living within their range, snow leopards, Himalayan wolves and leopards all favour them, so they are hunted quite a bit.

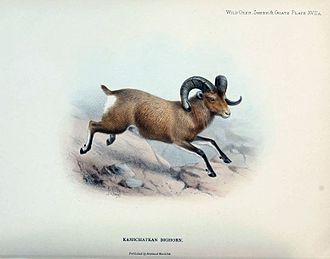

Bharal

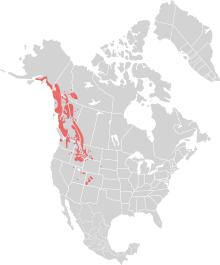

Mountain goat

The mountain goat is sometimes referred to as the rocky mountain goat, as this is where it is found. They are incredibly sure-footed, and can often be seen seemingly defying gravity, standing on the steepest of cliffs. This appears to be a defence strategy, as lower down the mountains, brown bears and black bears, as well as puma and wolves all predate this species.

The mountain goat is sometimes referred to as the rocky mountain goat, as this is where it is found. They are incredibly sure-footed, and can often be seen seemingly defying gravity, standing on the steepest of cliffs. This appears to be a defence strategy, as lower down the mountains, brown bears and black bears, as well as puma and wolves all predate this species.

Despite its name, it is not a true goat, instead being closely related to goat-like animals from around the world, such as chamois of Europe and the Takin, Serow and Gorals of Asia.

Their conservation status is least concern, with an estimated population of 80,000-110,000 in the wild. They spend most of their lives grazing. They have never been domesticated, though in places their fur has been used for wool. Another significant threat is avalanches in Alaska, where mortality from this threat is estimated at between 23% to a whooping 65% of the population.

Himilayan Tahr

Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern India, western Bhutan and Nepal. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List, as the population is declining due to both hunting and habitat loss – with the population in its native range thought to be around 2200.

Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern India, western Bhutan and Nepal. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List, as the population is declining due to both hunting and habitat loss – with the population in its native range thought to be around 2200.

They also have populations in The Himalayan tahr has been introduced to Argentina (Introduced in 2006 however some are claiming that they are now exterpirated in Argentina), New Zealand (an estimated 35000 in the southern alps, first introduced in 1904), South Africa (a pair escaped in the 1930s – however, when their population began to impact the native klipspringer they were extensively culled- if there are any left there are not many) and the United States where they have been released.

It is mostly a grazer, with around 75% of its nutrients coming from this.

Musk Ox

From the genus Ovibos, this map shows their range (blue is reintroductions, while red is historic range. In the long past, there were a variety of species that looked very much like this, however, not any more. The also evolved in Asia, before spreading to Europe and over to America. This map is hard to read, but they are found in Arctic areas of Alaska, Canada and Greenland. They also appeared to survive in Siberia until around 2700 years ago.

From the genus Ovibos, this map shows their range (blue is reintroductions, while red is historic range. In the long past, there were a variety of species that looked very much like this, however, not any more. The also evolved in Asia, before spreading to Europe and over to America. This map is hard to read, but they are found in Arctic areas of Alaska, Canada and Greenland. They also appeared to survive in Siberia until around 2700 years ago.

- Bos moschatus Zimmermann, 1780

- Bosovis moschatus (Zimmermann, 1780) Kowarzik, 1911

- Ovibos pallantis Hamilton-Smith, 1827

Along with the Bison and the pronghorn antelope, they are thought to be the only survivors from previous ages in their habitat.

They are thought to have a population of around 80,000-125,000 and are classed as least concern.

Nilgiri Tahr

Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern India, western Bhutan and Nepal. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List, as the population is declining due to both hunting and habitat loss – with the population in its native range thought to be around 2200.

Thy Himalayan Tahr is another species of Tahr found in the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern India, western Bhutan and Nepal. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List, as the population is declining due to both hunting and habitat loss – with the population in its native range thought to be around 2200.

They also have populations in The Himalayan tahr has been introduced to Argentina (Introduced in 2006 however some are claiming that they are now exterpirated in Argentina), New Zealand (an estimated 35000 in the southern alps, first introduced in 1904), South Africa (a pair escaped in the 1930s – however, when their population began to impact the native klipspringer they were extensively culled- if there are any left there are not many) and the United States where they have been released.

It is mostly a grazer, with around 75% of its nutrients coming from this.

Takin

The takin, also known as cattle chamois or gnu goat, is a large species of ungulate found in the eastern Himalayas. It includes four subspecies:

- Mishmi takin (B. t. taxicolor),

- Golden takin (B. t. bedfordi),

- Tibetan (or Sichuan) takin (B. t. tibetana)

- Bhutan takin (B. t. whitei).

Whilst the takin has in the past, been thought of as in the same family as the Musk ox, more recent mitochondrial research shows a closer relationship to Ovis (sheep),and the similar look is simply down to convergent evolution. The takin is the national animal of Bhutan. They are considered vulnerable to extinction, with an estimated population of between 7000-12000 (though it is unclear even how reliabe that estimate is).

Takin are found from forested valleys to rocky, grass-covered alpine zones, at altitudes between 1,000 and 4,500 m above sea level. The Mishmi takin occurs in eastern Arunachal Pradesh, while the Bhutan takin is in western Arunachal Pradesh and Bhutan. Dihang-Dibang Biosphere Reserve in Arunachal Pradesh, India is a stronghold of both Mishmi, Upper Siang (Kopu) and Bhutan takins.

Tibetan Antelope

The Tibetan antelope also known as Chiru, is found in the area shown in the map to the left and is a medium-sized bovid native to the north-eastern Tibetan plateau. Most of the population live within the Chinese border, while some scatter across India and Bhutan in the high altitude plains, hill plateau and montane valley.

The Tibetan antelope also known as Chiru, is found in the area shown in the map to the left and is a medium-sized bovid native to the north-eastern Tibetan plateau. Most of the population live within the Chinese border, while some scatter across India and Bhutan in the high altitude plains, hill plateau and montane valley.

Fewer than 150,000 mature individuals are left in the wild, but the population is currently thought to be increasing – they are not considered as threatened. They became threatened during the 1980s and 1990s, as they were heavily illegally poached largely for their underfur, which is knitted into shawls which usually go for $1000-$5000 (in India), but can go for a great deal more.

A special adaptation of the species to its high altitude habitat is the retention of the fetal version of hemoglobin even in adult animals, which provides higher oxygen affinity. The Tibetan antelope is the only species of mammal where this adaptation has been documented.

Alpine Ibex

The Alpine Ibex is found throughout much of the Alps (as you can see in the map). It is also known as the Capra ibex, and the Steinbock.

The Alpine Ibex is found throughout much of the Alps (as you can see in the map). It is also known as the Capra ibex, and the Steinbock.

There are 10 species within this Capra genus, with the nearest relative being the Iberian Ibex. They have been found at altitude of up to 3300m and are one of the species capable of climbing incredibly steep cliffs.

They eat mostly grasses, and while social, males and females only meet to breed.

While they are now least concern, the population dropped as low as 100 in the last century, which resulted in a genetic bottleneck. These 100 lived in Gran Paradiso national park in Italy, so all are now more closely related.

While wolves bears and lynx will take ibex, and do, the majority die as a result of parasites and disease.

They are thought to have a population of over 30,000 at the current time.

Domestic goat

Domestic goats are descended from the wild Bezoar goat, which was domesticated around 10,000 years ago in Iran.

As domestic animals, they fall beyond the perview of this website, but the Bezoar Ibex is a different matter.

The Bezoar ibex range is shown in the map to the left of this text. Unfortunately, they are not doing well, with only a few thousand left in the wild, primarily arouund the Caucasus.

The Bezoar ibex range is shown in the map to the left of this text. Unfortunately, they are not doing well, with only a few thousand left in the wild, primarily arouund the Caucasus.

Iberian Ibex

The iberian Ibex is found throughout much eastern Iberian peninsular, with sporadic range in other parts of the peninsular. It is listed as least concern. There have been 4 subspecies identified but 2 are extinct. The surviving species are the western Iberian ibex and the Southeastern Iberian ibex (also known as the Beceite Ibex). They have an estimated combined population of 50,000 left in the wild. They are classed as least concern.

The iberian Ibex is found throughout much eastern Iberian peninsular, with sporadic range in other parts of the peninsular. It is listed as least concern. There have been 4 subspecies identified but 2 are extinct. The surviving species are the western Iberian ibex and the Southeastern Iberian ibex (also known as the Beceite Ibex). They have an estimated combined population of 50,000 left in the wild. They are classed as least concern.

Markhor

The Markhor is found through the green areas on the map (The markhor is a large wild Capra (goat) species native to South Asia and Central Asia, mainly within Pakistan, the Karakoram range, parts of Afghanistan, and the Himalayas. It is listed on the IUCN Red List as Near Threatened since 2015.)

The Markhor is found through the green areas on the map (The markhor is a large wild Capra (goat) species native to South Asia and Central Asia, mainly within Pakistan, the Karakoram range, parts of Afghanistan, and the Himalayas. It is listed on the IUCN Red List as Near Threatened since 2015.)

The current population estimate is 5000-6000, up from a former population of around 2500. They are listed as not threatened.

They graze in the summer, but browse in the winter, when there is not as much grazing on offer, they switch to browsing. Roughly 32% of the population is adult female, 31% kids, 19% is mature males, while 12% is the subadult males. The last 9% is made up of yearling females (1-2 years).

Early in the season, males and females live in the valley where they can browse easily. During the summer, the females climb to the highest ridges above, but then in the spring, they stay closer to cliffs in areas with more rock coverage to provide protection for their offspring while the males move to higher elevated areas with more access to vegetation for foraging so as to improve their body’s condition.

Main predators include Eurasian lynx, Snow leopard, Brown bear and Himalayan wolf, while golden eagles are thought to prey on young markhor.

We cause Markhor deaths through overhunting for meat (as well as trophy hunting for horns), as well as feral dogs occasionally hunting the Markhor.

Other. more indirect threats include deforestation, military activity, competition with livestock, habitat fragmentation and (as often comes with this) genetic isolation.

It is the national animal of Pakistan

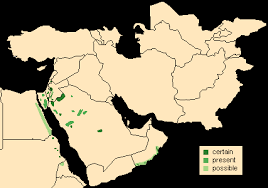

Nubian Ibex

The Nubian Ibex has a relatively restricted range (as can be seen from the map to the left). The population across this area is under 5000, with the largest population in Israel (1200-1400). It is considered vulnerable. Their population has remained surprisingly stable over the last 10,000 years as the advent of domestic animals came in. Nubian Ibex, like other Ibex species take refuge on impossibly steep cliffs, and are more and more viligant the farther they are from these safe zones. This nimbleness also allows them to climb trees.

The Nubian Ibex has a relatively restricted range (as can be seen from the map to the left). The population across this area is under 5000, with the largest population in Israel (1200-1400). It is considered vulnerable. Their population has remained surprisingly stable over the last 10,000 years as the advent of domestic animals came in. Nubian Ibex, like other Ibex species take refuge on impossibly steep cliffs, and are more and more viligant the farther they are from these safe zones. This nimbleness also allows them to climb trees.

Their main predators include Arabian leopards, arabian wolves, caracals, jackals and red foxes, as well as birds including golden eagles, bearded vultures and European eagle owls.

They can hybridize with goats, which may become a threat to their population.

Siberian Ibex

The Siberian ibex is also known using regionalized names including Altai ibex, Asian ibex, Central Asian ibex, Gobi ibex, Himalayan ibex, Mongolian ibex or Tian Shan ibex.

The Siberian ibex is also known using regionalized names including Altai ibex, Asian ibex, Central Asian ibex, Gobi ibex, Himalayan ibex, Mongolian ibex or Tian Shan ibex.

Though some recent authorities treat the species one, others have recognized four subspecies:

- C. s. sibirica (Siberian or Altai Ibex) – Sayan Mountains

- C. s. alaiana (Tian Shan Ibex) – Alay Mountains

- C. s. hagenbecki (Gobi or Mongolian Ibex) – western Mongolia

- C. s. sakeen (Himalayan Ibex) – Pamir Mountains, western Himalayas, India, Afghanistan and Pakistan

Usually living at high elevation (often around the plant line, well above the tree line) they will descend for food, in inclement weather and when it gets too hot.