Photo credit Tae Eke

Kiwi

It is thought that around 70,000 Kiwi remain on the two islands of new Zealand. One might think that this was high, but it is estimated that there were around 12 million before humans arrived – so around 0.5% of the population survives. More importantly, this is after a great deal of work has been done by many grassroot groups, in order to shore up the population – it has been far lower in the past.

Furthermore, roughly 2% of the umanaged kiwi are lost each week (around 20 birds). When well protected, a kiwi can live 25-50 years.

Rowi Kiwi

The rarest species, there are only thought to be around 450 of this bird remaining (as of last full survey in 2015). It is found in Ōkārito forest and surrounds in South Westland, predator-free islands of Marlborough Sounds, this is one of 5 designated kiwi sanctuaries declared in 2000.

As you can see, Kiwi is not a species but a group of species. While different species have been known to breed where their range overlaps, saving each species is a separate task

Tokoeka Kiwi

Translating to Weka with a walking stick, this species

- Haast tokoeka is Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable 400

- Southern Fiordland is Threatened – Nationally Endangered

- Northern Fiordland tokoeka is Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable

- Rakiura tokoeka is At Risk – Naturally Uncommon

Stoats are the main threat, with the total population numbering around 13000

Great Spotted Kiwi

Current population 14,000, it is restricted to the upper parts of the south islands national parks – specifically Sub-alpine zones of North West Nelson, the Paparoa Range, and Arthur’s Pass.

The largest species, it is thought to be declining by around 1.6% a year.

There are 4 genetically distinct populations Northwest Nelson, Westport, Paparoa Range and Arthur’sPass–Hurunui.

There are plans in place to save the species but time will tell if they prove successful.

Little spotted Kiwi

With a population of 1670it is found on Kapiti island (1200 are found on Kapiti island, from 5 translocated to the island early in teh 20th century) and 10 other pest free areas.

They start feeding themselves and roaming alone at 5-7 days, though they will return to the nest for around 60.

Each population is either stable or growing, so the overall trend is up.

Brown Kiwi

Living in lowland and coastal native forest and subalpine areas in the North Island, there are around 26,000 of this species. Although the most numerous, the population is reducing around 2-3% each year. It is estimated that without a change it will be lost in 2 generations.

Having said this, they have a greater capacity to recover, as unlike other species, they usually produce 2 eggs each time they mate, and can produce 2 clutches a year.

There are 4 distinct subspecies which live in different areas and do not interbreed.

- Northland brown kiwi 8000

- Coromandel brown kiwi 1700

- Western brown kiwi 8000

- Eastern brown kiwi 8000

Main threats is from predation by dogs.

As always, we are keen to add links that will allow people to book to see these animals in the wild. If you work as a tour guide or similar, do get in touch – click on list your wild place on the home page.

Bringing the Kiwi back to Wellington wilds

- Tim

- January 11, 2023

The Kiwi is an interesting bird. As with many birds that developed on islands without mammals, they cannot fly.

The aardwolf is the smallest member of the Hyaenidae family, as you can see from the map, it is a species with two separated populations, one in East Africa and one in Southern Africa. It is insectivorous, and exclusively nocturnal, and is generally thought of as one of the harder animals to see in the wild. If incredibly lucky, you can see them feeding alongside Aardvarks, and even Pangolins, but this is rare. They favour open dry plains and savannahs.

The aardwolf is the smallest member of the Hyaenidae family, as you can see from the map, it is a species with two separated populations, one in East Africa and one in Southern Africa. It is insectivorous, and exclusively nocturnal, and is generally thought of as one of the harder animals to see in the wild. If incredibly lucky, you can see them feeding alongside Aardvarks, and even Pangolins, but this is rare. They favour open dry plains and savannahs.

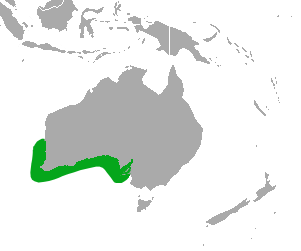

only endemic pinniped found in Australia.

only endemic pinniped found in Australia. the west coast of north America. On this map, the navy blue marks the breeding rance, while the light blue shows the total range that they can be found in. It should be noted, that previously the Japanese and Galapagos sealion were both considered subspecies of the Californian species, but no longer. They can stay healthy, for a time, in fresh water, and have been seen living for a while in Bonneville dam – 150 miles inland.

the west coast of north America. On this map, the navy blue marks the breeding rance, while the light blue shows the total range that they can be found in. It should be noted, that previously the Japanese and Galapagos sealion were both considered subspecies of the Californian species, but no longer. They can stay healthy, for a time, in fresh water, and have been seen living for a while in Bonneville dam – 150 miles inland. on all of the Galapagos Islands, as well as (in smaller numbers) on Isla de la Plata, which is just 40km from Puerto López a village in Ecuador. There have also been recorded sightings on the Isla del Coco which is 500km southwest of Costa Rica (and 750km from the Galapagos). These are not regular, and so have been considered vagrant. It is of course possible that historically they roamed here, but we cannot say.

on all of the Galapagos Islands, as well as (in smaller numbers) on Isla de la Plata, which is just 40km from Puerto López a village in Ecuador. There have also been recorded sightings on the Isla del Coco which is 500km southwest of Costa Rica (and 750km from the Galapagos). These are not regular, and so have been considered vagrant. It is of course possible that historically they roamed here, but we cannot say. known as the Hooker sealion) is native to south island, though before 1500 it is thought that it was also found on north island. They tend to breed on Subarctic islands of Auckland and Campbell (99% of the pups are born in these islands). In 1993, sealions started breeding on South Island again for the first time in 150 years.

known as the Hooker sealion) is native to south island, though before 1500 it is thought that it was also found on north island. They tend to breed on Subarctic islands of Auckland and Campbell (99% of the pups are born in these islands). In 1993, sealions started breeding on South Island again for the first time in 150 years.

The Iberian wolf is a subspecies of the grey wolf found on the Iberian peninsular. It reached its minimum in the 1970s with 500-700 iindividuals living in the wild. Until the middle of the 19th century, it was widespread, throughout the Iberian peninsular. It should be noted, that wolves have never had high densities, and the wolves of western Europe are not thought to have ever had a population much above 848–26 774 (depending on which end of the estimate you rely – but is the founding population of both the Iberian and Apennine population).

The Iberian wolf is a subspecies of the grey wolf found on the Iberian peninsular. It reached its minimum in the 1970s with 500-700 iindividuals living in the wild. Until the middle of the 19th century, it was widespread, throughout the Iberian peninsular. It should be noted, that wolves have never had high densities, and the wolves of western Europe are not thought to have ever had a population much above 848–26 774 (depending on which end of the estimate you rely – but is the founding population of both the Iberian and Apennine population).

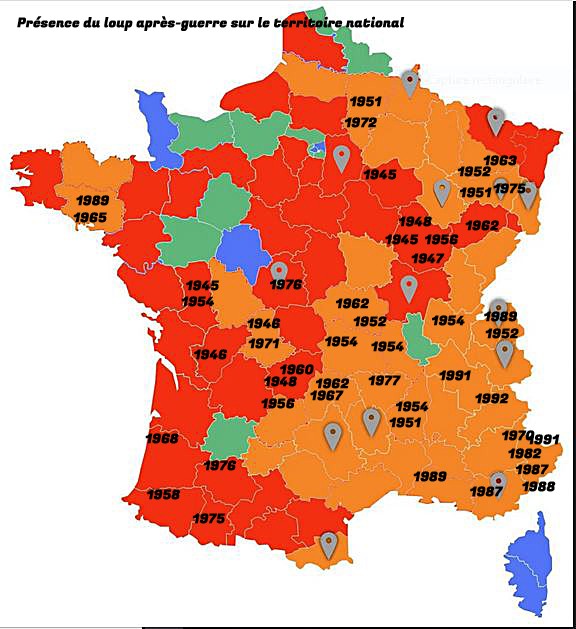

The Apennine wolf is also known as the Italian wolf. Back in the 1970s the population reached its minimum, where the population reached 70-100 individuals. It has recovered well since then, with an Italian population of roughly 3300. However, since the early 1990s, this subspecies has been gradually moving into France. As such, at the end of 2022 the number was estimated at 1104 wolves in France.

The Apennine wolf is also known as the Italian wolf. Back in the 1970s the population reached its minimum, where the population reached 70-100 individuals. It has recovered well since then, with an Italian population of roughly 3300. However, since the early 1990s, this subspecies has been gradually moving into France. As such, at the end of 2022 the number was estimated at 1104 wolves in France.

The Eurasian wolf (often referred to as the Russian wolf), is the subspecies which runs down the east coast of the Adriatic sea, as well as the majority of Russia and northern Europe.

The Eurasian wolf (often referred to as the Russian wolf), is the subspecies which runs down the east coast of the Adriatic sea, as well as the majority of Russia and northern Europe.

The Tundra wolf – Canis lupus Albus is the Eurasian equivalent of the Arctic wolf. Also known as the Turukhan wolf, it is native to Eurasia’s tundra and forest-tundra zones from Finland to the Kamchatka Peninsula. It was first described in 1792 by Robert Kerr.

The Tundra wolf – Canis lupus Albus is the Eurasian equivalent of the Arctic wolf. Also known as the Turukhan wolf, it is native to Eurasia’s tundra and forest-tundra zones from Finland to the Kamchatka Peninsula. It was first described in 1792 by Robert Kerr.

The Indian wolf is one of the more well known, partly as their starring role in the Jungle book by Rudyard Kipling. I do remember my great grandmother talking about seeing 4 wolves running in the distance. It is thought to have 2000-3000 individuals left in the wild, though given its former large range, this does not appear very high. It should not be surprising, therefore, to hear that this is considered as one of the most endangered subspecies of the grey wolf – it officially has the conservation status of endangered – now it is considered endangered, and people talk about it at high risk, but it should be remembered that there are still 2000-3000, which is a pretty high number for a species considered more than just endangered.

The Indian wolf is one of the more well known, partly as their starring role in the Jungle book by Rudyard Kipling. I do remember my great grandmother talking about seeing 4 wolves running in the distance. It is thought to have 2000-3000 individuals left in the wild, though given its former large range, this does not appear very high. It should not be surprising, therefore, to hear that this is considered as one of the most endangered subspecies of the grey wolf – it officially has the conservation status of endangered – now it is considered endangered, and people talk about it at high risk, but it should be remembered that there are still 2000-3000, which is a pretty high number for a species considered more than just endangered.

The Steppe wolf also known as the Caspian sea wolf is a wolf subspecies that is found in the region around the Caspian sea, though the Steppe wolf is perhaps more useful a name as it extends far from the Caspian sea. Much of its range is in Kazakhstan as the working figure is 30,000 individuals, however, the survey which produced this number was completed in 2007, and given the lack of any protection and the widespread enjoyment, got from hunting wolves, it seems highly unlikely that the current population is anywhere near that size.

The Steppe wolf also known as the Caspian sea wolf is a wolf subspecies that is found in the region around the Caspian sea, though the Steppe wolf is perhaps more useful a name as it extends far from the Caspian sea. Much of its range is in Kazakhstan as the working figure is 30,000 individuals, however, the survey which produced this number was completed in 2007, and given the lack of any protection and the widespread enjoyment, got from hunting wolves, it seems highly unlikely that the current population is anywhere near that size.

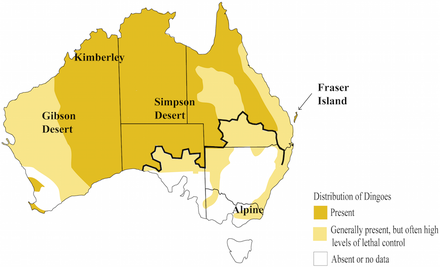

Closely related to the new Guinea singing dog, the Dingo is a dog species that has a relatively wide range. There is some debate about how it got to some of its homes, and whether it may have come alongside early humans.

Closely related to the new Guinea singing dog, the Dingo is a dog species that has a relatively wide range. There is some debate about how it got to some of its homes, and whether it may have come alongside early humans.

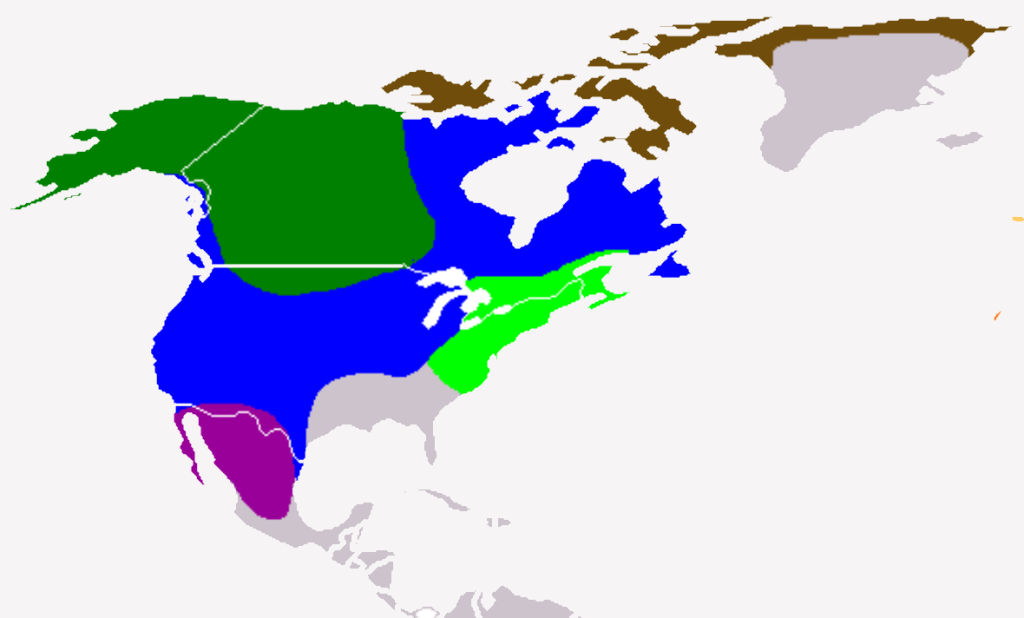

Mexican wolves (scientific name is Canis lupus baileyi) are currently only found in a small area as seen on the map to the right. It is a fantastic improvement on the situation around 1970 when the species was extinct in the wild. The first reintroduction was carried out in 1998. Unfortunately, founded by just 7 individuals, the population is highly inbred. Never-the-less, currently, the USA has 257 wild Mexican wolves, while 57 live across the border in Mexico, up from just 11 that were reintroduced into the wild. A further 380 are in captivity.

Mexican wolves (scientific name is Canis lupus baileyi) are currently only found in a small area as seen on the map to the right. It is a fantastic improvement on the situation around 1970 when the species was extinct in the wild. The first reintroduction was carried out in 1998. Unfortunately, founded by just 7 individuals, the population is highly inbred. Never-the-less, currently, the USA has 257 wild Mexican wolves, while 57 live across the border in Mexico, up from just 11 that were reintroduced into the wild. A further 380 are in captivity.