The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin is a species of Bottlenose dolphin. This dolphin grows to 2.6 m long, and weighs up to 230 kg . It lives in the waters around northern Australia , South China, the Red Sea, and the eastern coast of Africa. Its back is dark grey and its underside is lighter grey or nearly white with grey spots. The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin is usually smaller than the Common bottlenose dolphin, has a proportionately longer Rostrum, and has spots on its belly and lower sides. It also has more teeth than the common bottlenose dolphin — 23 to 29 teeth on each side of each jaw compared to 21 to 24 for the common bottlenose dolphin.

Much of the old scientific data in the field combine data about the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin and the common bottlenose dolphin into a single group, making it effectively useless in determining the structural differences between the two species. The IUCN lists the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin as “near threatened” in their Red List of endangered species.

Until 1998, all bottlenose dolphins were considered members of the single species Tursiops truncatus. In that year, the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin was recognized as a separate species. Both species are thought to have split during the mid-Pleistocene, about 1 million years ago. Some evidence shows the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin may actually be more closely related to certain dolphin species in the Delphinus (genus), especially the “Atlantic spotted dolphin”, than it is to the common bottlenose dolphin. However, more recent studies indicate that this is a consequence of reticulate evolution (such as past hybridization between Stenella and ancestral Tursiops and incomplete lineage sorting, and thus support truncatus and T. aduncus belonging to the same genus. Burrunan dolphin T. (aduncus) australis has been alternately considered its own species, a subspecies of T. truncatus, or a subspecies of T. aduncus. Following the results of a 2020 study, the American Society of Mammologists presently classifies it as a subspecies of T. aduncus. The same study delineated 3 distinct lineages within T. aduncus which could each be their own subspecies: an Indian Ocean lineage, an Australasian lineage, and the Burrunan dolphin. The Society for Marine Mammalogy does not recognize the Burrunan dolphin as a distinct species or subspecies, citing the need for further research. Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins are very similar to common bottlenose dolphins in appearance. Common bottlenose dolphins have a reasonably strong body, moderate-length beak, and tall, curved dorsal fins; whereas Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins have a more slender body build and their beak is longer and more slender.

Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins feed on a wide variety of fish Cephalopod, Squid, researchers looked at the feeding ecology of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins by analysing the stomach contents of ones that got caught in the gillnet fisheries off Zanzibar, Tanzania. Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins live in groups that can number in the hundreds, but groups of five to 15 dolphins are most common.

In some parts of their range, they spend time with the common bottlenose dolphin and other dolphin species, such as the humpback dolphin. The peak mating and calving seasons are in the spring and summer, although mating and calving occur throughout the year in some regions. Gestation period is about 12 months. Calves are between 0.84 and 1.5 Meters, and weigh between 9 and 21kg. The calves are weaned between 1.5 and 2.0 years, but can remain with their mothers for up to 5 years, some mothers will give birth again, shortly before the 5 years are up.

In some parts of its range, this dolphin is subject to predation by sharks.

Its lifespan is more than 40 years. Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins located in Shark Bay, Australia, have been observed using sponges as tools in a practice called “sponging”. A dolphin breaks a marine sponge off the sea floor and wears it over its rostrum, apparently to probe substrates for fish, possibly as a tool. Spontaneous ejaculation in an aquatic mammal was recorded in a wild Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin near Mikura Island, Japan, in 2012. Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins have been observed to swim near and rub themselves against specific types of corals and sponges. A team of scientists followed up on this behaviour and discovered metabolites with antibacterial, antioxidative, and hormonal activities in the corals and sponges, suggesting that they might be used by the dolphins to treat skin infections. its near-shore distribution, though, makes it vulnerable to environmental degradation, direct exploitation, and problems associated with local fisheries.

The major predators of this species are typically sharks, and may include humans, killer whales, and sting rays. In the early 1980s, many were deliberately killed in a Taiwanese driftnet fishery in the Arafura Sea, off north western Australia. Large-mesh nets set to protect bathers from sharks in South Africa and Australia have also resulted in a substantial number of deaths. Gillnets are also having an impact, and are a problem throughout most of the species’ range.

These small cetaceans are commonly found in captivity, causing conservation concerns, including the effects of removing the animals from their wild populations, survival of cetaceans during capture and transport and while in captivity, and the risks to wild populations and ecosystems of accidentally introducing alien species and spreading epizootic diseases, especially when animals have been transported over long distances and are held in sea pens.

Bottlenose dolphins are the most common captive cetaceans on a global scale. Prior to 1980, more than 1,500 bottlenose dolphins were collected from the United States, Mexico, and the Bahamas, and more than 550 common and 60 Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins were brought into captivity in Japan. By the late 1980s, the United States stopped collecting bottlenose dolphins and the number of captive-born animals in North American aquaria has increased from only 6% in 1976 to about 44% in 1996. South Korea, in the 2010s, environmental groups and animal protection groups led a campaign ko:2013 to release southern bottlenose dolphins illegally captured by fishermen and trapped in Jeju Island.

In a study on three populations of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins in Japan, the characteristics of acoustic signals are believed to be affected by the acoustic environments among habitats, and geographical variation in animal acoustic signals can result from differences in acoustic environments; therefore, the characteristics of the ambient noise in the dolphins’ habitats and the whistles produced were compared. Ambient noise was recorded using a hydrophone located 10 m below the surface and whistles were recorded by using an underwater video system. The results showed dolphins produced whistles at varying frequencies with greater modulations when in habitats with less ambient noise, whereas habitats with greater ambient noise seem to cause dolphins to produce whistles of lower frequencies and fewer frequency modulations. Examination of the results suggest communication signals are adaptive and are selected to avoid the masking of signals and the decrease of higher-frequency signals. They concluded ambient noise has the potential to drive the variation in whistles of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin populations.

Small, motorized vessels have increased as a source of anthropogenic noise due to the rise in popularity of wildlife viewing such as whale watching. Another study showed powerboat approaches within 100 m altered the dolphin surface behaviour from traveling to milling, and changed their direction to travel away from the powerboat. When the powerboat left the area and its noise ceased, the dolphins returned to their preceding behaviour in the original direction.

In Shark Bay, Western Australia, on dolphin behavioural responses showed significant changes in the behaviour of targeted dolphins were found when compared with their behaviour before and after approaches by small watercraft. Dolphins in the low-traffic site showed a stronger and longer-lasting response than dolphins in the high-traffic site. These results are believed to show habituation of the dolphins to the vessels in a region of long-term vessel traffic. However, when compared to other studies in the same area, moderated responses, rather, were suggested to be because those individuals sensitive to vessel disturbance left the region before their study began. Although these studies do show statistical significance for the effects of whale-watching boats on behaviour, what these results mean for long-term population viability is not known. The Shark Bay population has been forecast to be relatively stable with little variation in mortality over time. The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin populations of the Arafura and the Timor Sea are listed on Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals “Bonn Convention”. They are listed on Appendix II as they have an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements. The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin is also covered by Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region Adelaide Dolphin Sanctuary “Marine protected area” in the Australian state of South Australia Gulf St Vincent, which was established in 2005 for the protection of a resident population of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins.

When we have links for viewing these species, they will appear below video and the news section

The

The

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species.

many as 70 subspecies, local variants and similar have been suggested, however there is only one currently recognized species. common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu.

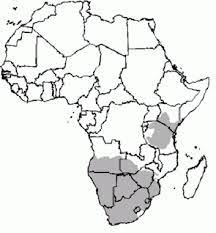

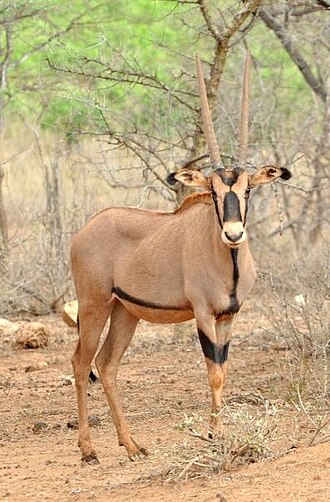

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

The gemsbok or South African oryx, is a large antelope in the genus Oryx. It is endemic to the dry and barren regions of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and (parts of) Zimbabwe, mainly inhabiting the Kalahari and Namib Deserts, areas in which it is supremely adapted for survival. Previously, some sources classified the related East African oryx, or beisa oryx, as a subspecies.

Impala

Impala antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

antelope, species with a handful of small populations acros central and western north Africa. It lives in the Sahara and the Sahel desert.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

The gerenuk is an odd species, which in appearance looks like a cross between an impala and a giraffe. They increase this effect, by standing on their hind legs while they eat. A herd, eating in this way is quite a weird sight.

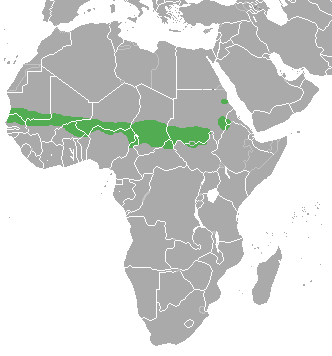

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle.

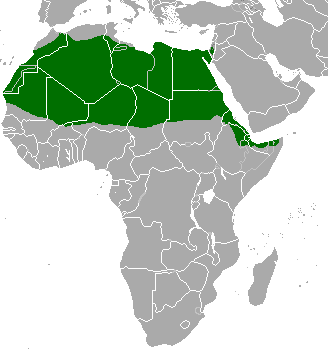

The red-fronted Gazelle is found in a wide but uneven band across the middle of Africa from Senegal to north-eastern Ethiopia. It mainly lives in the Sahel zone, a narrow cross-Africa band south of the Sahara, where it prefers arid grasslands, wooded savannas and shrubby steppes. There are some people who consider the more famous Thompson gazelle of east Africa a subspecies of the red-fronted Gazelle. Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

Also known as the Rhim gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder’s gazelle while its name in Tunisia and Egypt means white gazelle, it is pale and well suited to the desert, however there are only 2500 of them left in the wild. Widely found, they have populations across They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan (this can be seen on the map opposite).

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The Speke’s gazelle is the smallest gazelle and is found in the horn of Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia – though hunted to extinction in Ethiopia). They number roughly in the low 10,000s. Unfortunately having been hunted to extinction in Ethiopia, its one remaining home is a war zone, which does not give us reassurance that it will survive into the future. While the population has increased in recent times, the animal has recently been upgraded from vulnerable to endangered. It takes its name from John Hanning Speke, who was an English explorer in central Africa. It is similar to the Dorcas gazelle, and it has been considered a subspecies at times.

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

The common name “springbok”, first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring (“jump”) and bok (“antelope” or “goat”). It is only found in South Africa and the south west (including Namibia and southern Botswana and parts of Angola)

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

Also known as the Clarkes gazelle, it is another species restricted to Ethiopia and Somalia. It is not a true gazelle, though it does still have markings on its legs similar to the gazelles. They are classed as vulnerable, with their biggest threat being poaching.

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The Kirks dik-dik has two areas of habitat, oddly split, suggesting that at one point their range may have been far larger.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places.

The klipspringer has a large range, being found across a large range of Africa. In places like the Kruger, virtually ever outcrop of rock has a pair of klipspringers. They are able to stand on particularly steep rocks, which allows them to get away from predators. This is important, as when there are not large enough trees available, leopards will often live in similar places. A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

A small antelope, though found across a wide range of habitats. They are secretive, and as such are generally seen far less often than their population would suggest. They are rarely seen in the Kruger, but overall are not doing badly.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice.

The Sharpe’s Grysbok, is another small antelope that is found in the east of southern Africa (its most southerly point is the northern Kruger. As a small species, however, it is another antelope that can regularly pass without notice. The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

The steenbok (also known as steinbuck or steinbok) is a small species of antelope found in the southern and eastern Africa. Its closest relatives are the dik-diks and gazelles.

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

Also known as Nunga, and is found in Kenya and on the island of Zanzibar. It may be a subspecies of the red, Harvey’s, or Peters’s duiker or a hybrid of a combination of these – but is named after W Mansfield Aders – a zoologist with the Zanzibar government service. It is small, only standing 30cm at the shoulder, and weigh between 75.-12kg (the heaviest is in Zanzibar).

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black duiker is another species found in the rainforests of west Africa. It is estimated that there are 100,000 of this species in the wild, though how much faith can be placed in this number, is I think an important question. Standing roughly 50cm tall, and weighing 15-20kg.

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams.

The black-fronted duiker is found in central and west-central Africa, with an isolated population in the Niger Delta in eastern Nigeria and then from southern Cameroon east to western Kenya and south to northern Angola, and occurs in montane, lowland, and swamp forests, from near sea level up to an altitude of 3,500m. It is frequently recorded in wetter areas such as marshes or on the margins of rivers or streams.  The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

The blue duiker is found in a wide range of habitats. While much of its range falls in countries like the Democratic republic of the Congo (and thereby makes the blue duiker a rainforest species) they also live in large parts of eastern Tanzania, and places like South Africa where there is no rainforest. The habitat consists of a variety of forests, including old-growth, secondary, and gallery forests.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink.

Jentink’s duiker also known as gidi-gidi in Krio and kaikulowulei in Mende, is a forest-dwelling duiker found in the southern parts of Liberia, southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, and scattered enclaves in Sierra Leone. It is named in honor of Fredericus Anna Jentink. A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

A small antelope found in west Africa, first described in 1827 by Charles Hamilton-Smith, it shares a genus with the blue duiker and the Walters duiker

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Also known as Red forest duiker (as well as other mixes of these words), is very similar to the common duiker. It is very similar to the common duiker with though with a redder coat.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

Measuring 34-37cm tall and 12-14kg, this small species of antelope. They are classed as least concern and have a large range with around 170,000 living in the wild. It has often done well out of deforestation, as it has often expanded its range during these times.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda.

This species range is shown on the map , and is found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, while it is likely to have been extirpated in Uganda. The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).

The yellow-backed duiker has a wide range of places it is found (ranging from Senegal and Gambia on the western coast, through to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to western Uganda; their distribution continues southward into Rwanda, Burundi, and most of Zambia).