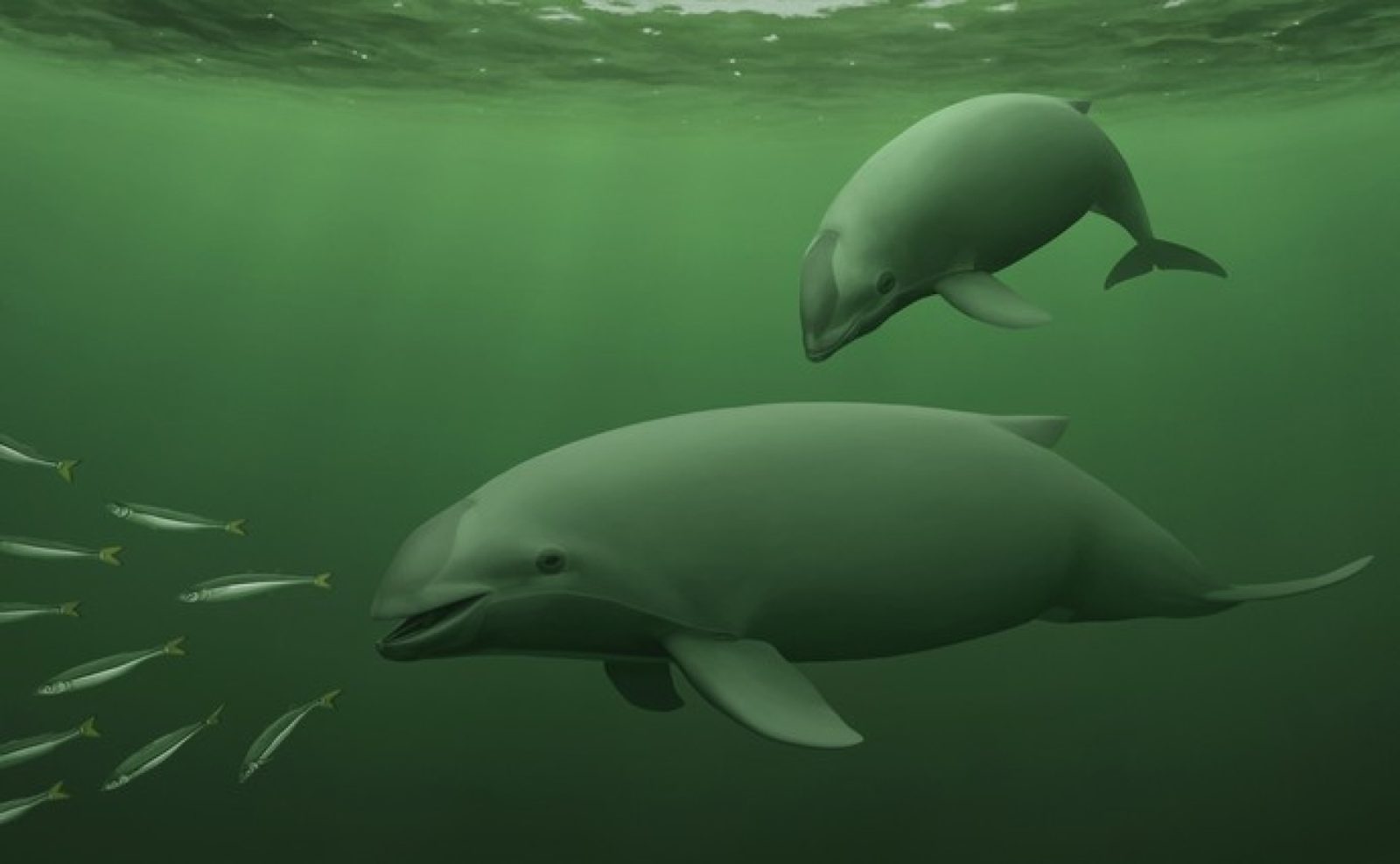

Indo-Pacific Finless dolphin

They are found in most of the Indian Ocean, as well as the tropical and subtropical Pacific from Indonesia north to the Taiwan Strait. Overlapping with this species in the Taiwan Strait and replacing it northwards is the East Asian finless porpoise.

They are one of the species protected by the Sundarbans national park, which lies between India and Bangladesh.

Growing to 2.3m at most, and with a weight of up to 72kg (most individuals are far, far, smaller). They eat a wide range of foods from fish and crustations to vegetation such as leaves and rice, and eggs that have been deposited on these leaves.

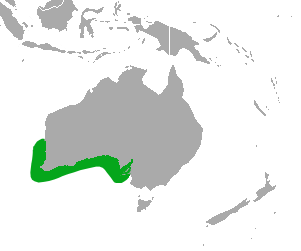

only endemic pinniped found in Australia.

only endemic pinniped found in Australia. the west coast of north America. On this map, the navy blue marks the breeding rance, while the light blue shows the total range that they can be found in. It should be noted, that previously the Japanese and Galapagos sealion were both considered subspecies of the Californian species, but no longer. They can stay healthy, for a time, in fresh water, and have been seen living for a while in Bonneville dam – 150 miles inland.

the west coast of north America. On this map, the navy blue marks the breeding rance, while the light blue shows the total range that they can be found in. It should be noted, that previously the Japanese and Galapagos sealion were both considered subspecies of the Californian species, but no longer. They can stay healthy, for a time, in fresh water, and have been seen living for a while in Bonneville dam – 150 miles inland. on all of the Galapagos Islands, as well as (in smaller numbers) on Isla de la Plata, which is just 40km from Puerto López a village in Ecuador. There have also been recorded sightings on the Isla del Coco which is 500km southwest of Costa Rica (and 750km from the Galapagos). These are not regular, and so have been considered vagrant. It is of course possible that historically they roamed here, but we cannot say.

on all of the Galapagos Islands, as well as (in smaller numbers) on Isla de la Plata, which is just 40km from Puerto López a village in Ecuador. There have also been recorded sightings on the Isla del Coco which is 500km southwest of Costa Rica (and 750km from the Galapagos). These are not regular, and so have been considered vagrant. It is of course possible that historically they roamed here, but we cannot say. known as the Hooker sealion) is native to south island, though before 1500 it is thought that it was also found on north island. They tend to breed on Subarctic islands of Auckland and Campbell (99% of the pups are born in these islands). In 1993, sealions started breeding on South Island again for the first time in 150 years.

known as the Hooker sealion) is native to south island, though before 1500 it is thought that it was also found on north island. They tend to breed on Subarctic islands of Auckland and Campbell (99% of the pups are born in these islands). In 1993, sealions started breeding on South Island again for the first time in 150 years.