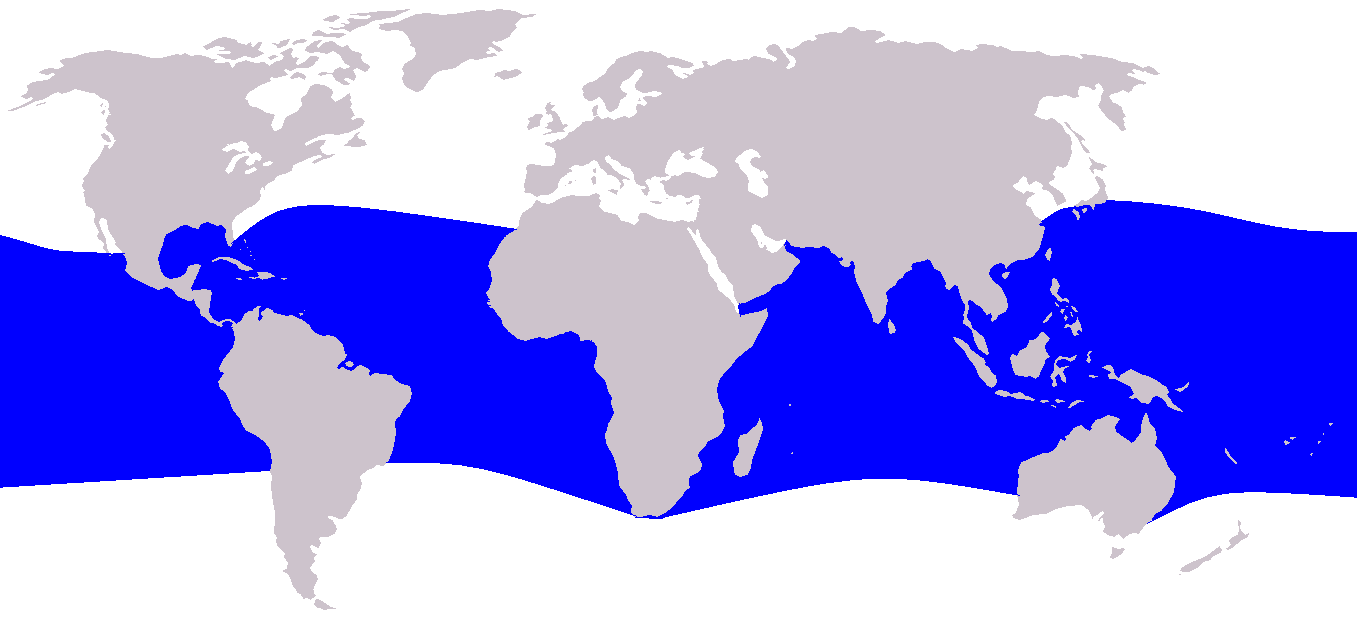

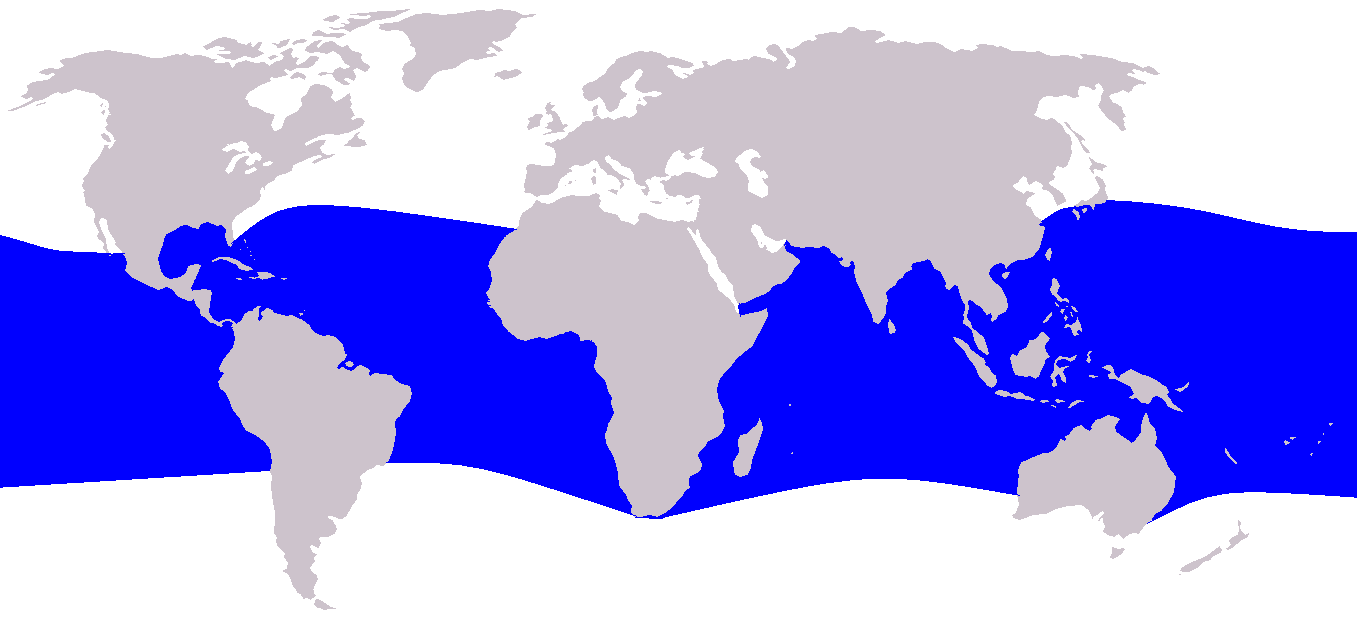

The melon-headed whale (other names  include electra dolphin, little killer whale, or many-toothed blackfish), is a toothed whale of the oceanic dolphin from the Delphinidae family. The common name came from the shape of the head. Melon-headed whales are widely distributed throughout deep tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, but they are rarely encountered at sea.

include electra dolphin, little killer whale, or many-toothed blackfish), is a toothed whale of the oceanic dolphin from the Delphinidae family. The common name came from the shape of the head. Melon-headed whales are widely distributed throughout deep tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, but they are rarely encountered at sea.

They are found near shore mostly around oceanic islands, such as Hawaii, French Polynesia, and the Philippines.

Melon-headed whales are a highly social species and usually travel in large groups of 100 – 500 individuals, with occasional sightings of herds as large as 1000–2000. Large herds appear to consist of smaller subgroups that aggregate into larger groups. Data from mass strandings in Japan suggest melon-headed whales may have a matrilineal social structure (i.e., related through female kin/groups organized around an older female and their relatives); the biased sex ratio (higher number of females) of the stranding groups suggesting mature males may move between groups. While melon-headed whales associate in large groups (a common trait amongst the oceanic dolphins, in contrast to the smaller group sizes of other blackfish species) their social structure may be more stable and intermediate between the larger blackfish (pilot whales, killer whales and false killer whales) and smaller oceanic dolphins. However, genetic studies of melon-headed whales across the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Ocean basins suggest that there is relatively high level of connectivity (inter-breeding) between populations. This indicates that melon-headed whales may not show strong fidelity to their natal group (the group into which the individual was born) and that there are higher rates of movement of individuals between populations than in other blackfish species. Larger group sizes may increase competition for prey resources, requiring large home ranges and broad-scale foraging movements. Observations of daily activity patterns of melon-headed whales near oceanic islands suggest they spend the mornings resting or logging in near-surface waters after foraging at night. Surface activity (such as tail slapping and spy-hopping) and vocalizations associated with socializing (communication whistles, rather than echolocation, clicks used for foraging) increase during the afternoons. The daily pattern of behaviour observed in island-associated populations, combined with the larger group sizes of melon-headed whales (compared to that typically seen in other blackfish species) is more similar to the fission-fusion spinner dolphins. These behavioural traits may relate to predation avoidance (bigger groups offer some protection from large oceanic sharks) and foraging habits (both species are nocturnal predators that prey on predictable, relatively abundant mesopelagic squid and fish that make diel vertical migrations from the deep-sea to the surface). Melon-headed whales frequently associate with Fraser’s dolphins, and are also sighted, although less commonly, in mixed herds with other dolphin species such as spinner dolphins, common bottlenose dolphins, rough-toothed dolphins, short-finned pilot whales and pantropical spotted dolphins. A unique case of inter-species adoption between (presumably) an orphaned melon-headed whale calf and a common bottlenose dolphin mother was recorded in French Polynesia. The calf was first observed in 2014 at less than one month of age, swimming with the bottlenose dolphin female and her own biological offspring. The melon-headed whale calf was observed suckling from the bottlenose dolphin female, and was repeatedly sighted with its adoptive/foster mother until 2018.In August 2017 off the island of Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi, a hybrid between a melon-headed whale and rough-toothed dolphin was observed travelling with a melon-headed whale amongst a group of rough-toothed dolphins. The hybrid superficially resembled a melon-headed whale, but closer observation revealed it had features of both species and some features intermediate between the two species, particularly in head shape. Genetic testing of a skin biopsy sample confirmed that the individual was a hybrid between a female melon-headed whale and a rough-toothed dolphin male.

Melon-headed whales may be predated upon by large sharks and killer whales.Scars and wounds from non-lethal bites of cookie cutter sharks have been observed on free-ranging and stranded animals.

Little is known about the reproductive behaviour of melon-headed whales. The most information comes from analyses of large stranding groups in Japanese waters, where sexual maturity for females is reached at 7 years of age. Females give birth to a single calf every 3–4 years after a gestation of approximately 12 months. Off Japan, the calving season appears to be long (from April to October) without an obvious peak. In Hawaiian waters newborn melon-headed whales have been observed in all months except December, suggesting births occur year-round, but sightings of newborns peak between March and June. Newborn melon-headed whales have been observed in April and June in the Philippines. In the Southern Hemisphere calving also appears to occur over an extended period, from August to December. Melon-headed whales are known to mass strand, often in groups numbering in the hundreds, indicative of the strong social bonds within herds of this species. Mass strandings of melon-headed whales have been reported in Hawaiʻi, eastern Japan, the Philippines, northern Australia, Madagascar, Brazil and the Cape Verde Islands. Two of these mass stranding events have been linked to anthropogenic sonar, associated with naval activities in Hawaiʻi and high frequency multi-beam sonar used for oil and gas exploration in Madagascar. The mass stranding at Hanalei Bay, Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi is more precisely described as a ‘near’ mass stranding event, as the group of 150 melon-headed whales was prevented from stranding by human intervention. The animals occupied the shallow waters of a confined bay for over 28 hours before being herded back into deeper waters by stranding response staff and volunteers, community members, state and federal authorities. Only a single calf is known to have died on this occasion. The frequency of mass strandings of melon-headed whales appears to have increased over the past 30+ years. Melon-headed whales are fast swimmers; they travel in large, tightly packed groups and can create a lot of spray when surfacing, often porpoising (repeatedly leaping clear of the water surface at a shallow angle) when travelling at speed, and are known to spyhop and also may jump clear out of the water. Melon-headed whales can be wary of boats, but in some regions will approach boats and bow-ride. The world population is unknown, but abundance estimates for large regions are approximately 45,000 in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean 2,235 in northern Gulf of Mexico and in the Philippines 920 in the eastern Tañon Strait, Negros Island. There are two known populations in Hawaiʻi: a population of approximately 450 individuals resident to shallower waters of the northwest side of Hawaiʻi Island (the ‘Kohola resident population’) and a much larger population of approximately 8,000 individuals that moves among the main Hawaiian Islands in deeper waters. Hawaiʻi Island resident population has a restricted range (sightings have only been recorded off the northwest side of Hawaiʻi Island), and at times most of, or the entire resident population can be together in a single group, there is some concern that this population may be at risk from fisheries interactions, and exposure to anthropogenic noise, particularly in light of U.S. Navy activities in the region, given the potential link between sonar and mass stranding events.

Whale watching

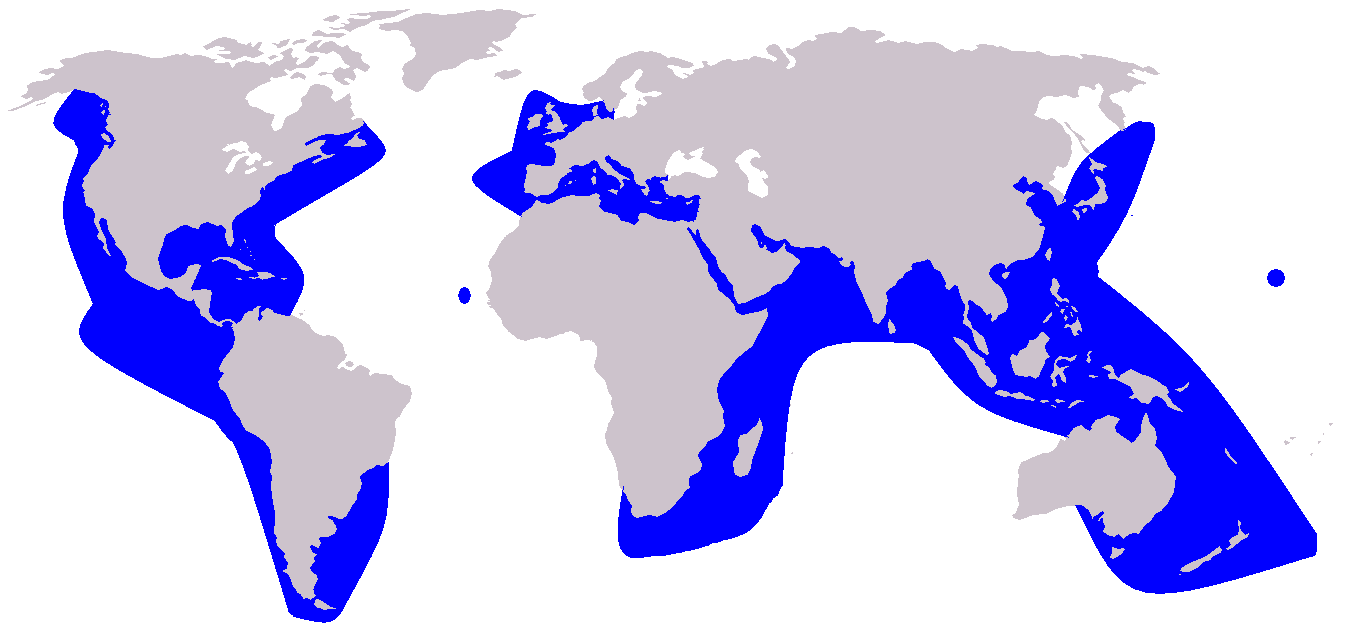

Regions in which melon-headed whales can be reliably sighted are few, however Hawai’i, the Maldives, the Philippines, and in the eastern Caribbean, especially around Dominica, are the best places to see them. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) has guidelines for whale watching to ensure minimum disturbance to wildlife, but not every operator adheres to them.

Negative impacts from humans range through noise pollution hunting and by-catch among others.

Conservation status

The melon-headed whale is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List. There is little information available on current levels of bycatch and commercial hunting, therefore the potential effects on melon-headed whale populations are undetermined. The current population trend is unknown.

The species is listed on Appendix II of (CITES). The melon-headed whale is included in the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia (Western African Aquatic Mammals MoU) and the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MoU). As with all other marine mammal species, the melon-headed whale is protected in United States waters under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA).

Below lists any posts which mention this species (i hope they will increase over time). Below this is a video, and below this, I will list any places where you can attempt to see this species.

one of the two species of cetaceans in the genus Globicephala, which it shares with the long-finned pilot whale It is part of the oceanic dolphin family (Delphinidae).

one of the two species of cetaceans in the genus Globicephala, which it shares with the long-finned pilot whale It is part of the oceanic dolphin family (Delphinidae).

include electra dolphin, little killer whale, or many-toothed blackfish), is a toothed whale of the oceanic dolphin from the Delphinidae family. The common name came from the shape of the head. Melon-headed whales are widely distributed throughout deep tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, but they are rarely encountered at sea.

include electra dolphin, little killer whale, or many-toothed blackfish), is a toothed whale of the oceanic dolphin from the Delphinidae family. The common name came from the shape of the head. Melon-headed whales are widely distributed throughout deep tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, but they are rarely encountered at sea.